A few paces into a walk one day, my friend’s dog found, nestled under a pile of autumn leaves, the most wonderful treasure the world could offer: a discarded box of half-eaten chicken wings. Before my friend could pull her dog away, the wings were gone—inhaled with the speed of an opportunist who knows better than to waste time on risk assessment. The miracle of free chicken left my friend’s dog forever changed: even years later, this ever-hopeful pup still checks the same spot every day, just in case someone decides to bless her with their scraps once more.

Prior experiences can shape many behaviors, including multitasking and even chess-playing. In the case of my friend’s dog, the rewarding experience of stumbling upon loose poultry seems to have focused her attention to this specific spot in their local park. The promise of potentially being rewarded again has nearly consumed her—she can not be distracted from her daily ritual of checking the blessed chicken spot.

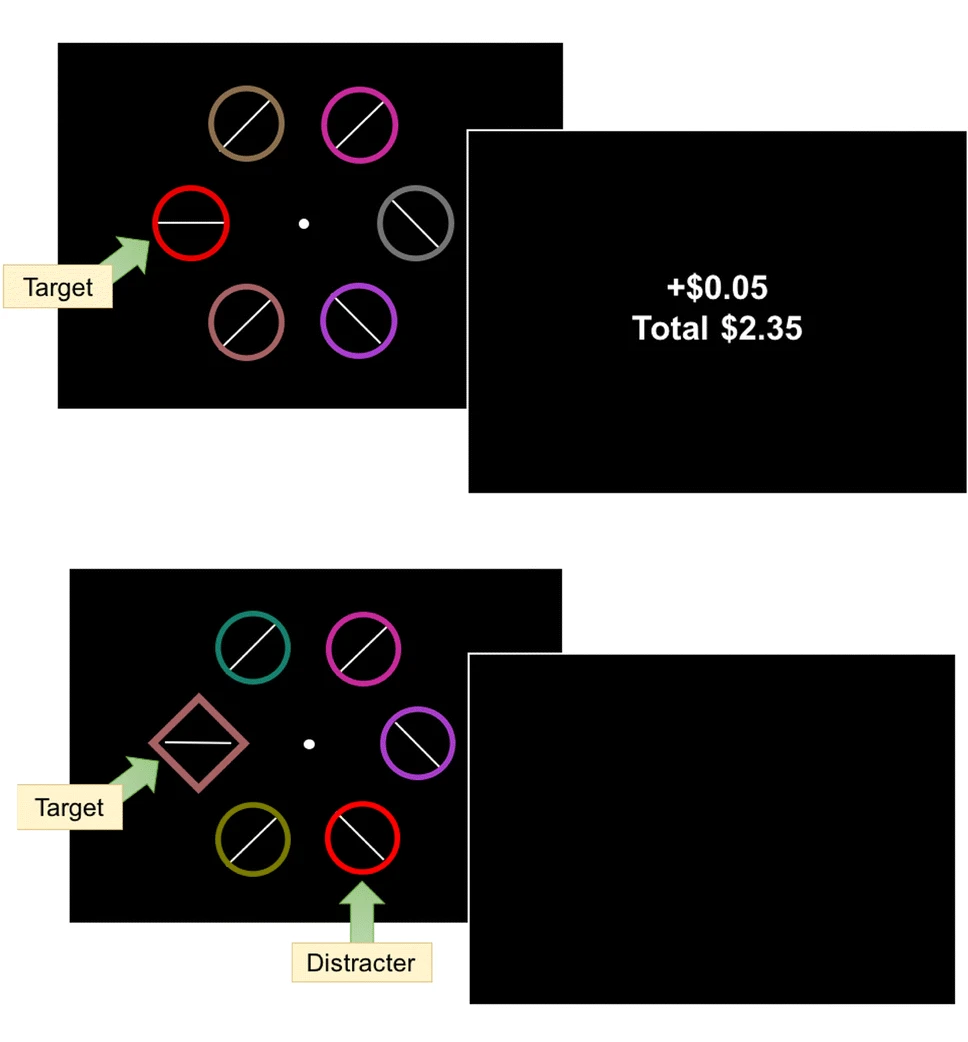

To study how prior experience potentially influences attention, cognitive psychologists often take advantage of a phenomenon known as value-driven attention capture (or VDAC for short). In VDAC studies, participants first take part in a “learning phase”, where they learn to associate certain visual details, such as color, with a reward. Traditionally, they are shown a display with six circles of different colors, all with lines running through their centers. The participants are instructed to look for red or blue circles, which will always have either a horizontal or a vertical line in them, and then they indicate whether the lines are horizontal or vertical by pressing different buttons. Importantly, one of the target colors (red or blue, but not both) will grant the participant more money as a reward.

About a week later, participants take part in a “test phase”, where they perform a similar visual search task. This time, participants are instructed to respond to different colors (such as orange or green). The trick, however, is that the colors that were previously targets in the learning phase are shown as distractors (one of the other shapes in the display) which participants will then need to ignore. Researchers then measure how fast their participants press the response buttons. In the test phase, they usually see that people are slower to respond to an orange or green circle if a red or blue shape is also on the display. This is presumably because they previously learned to associate either red or blue with reward, and that association interferes with their ability to quickly respond to the new target color.

VDAC paradigms are frequently used to study the capacity for long-term influences of rewarding experiences on attention, since VDAC patterns can be highly persistent, with some studies continuing to show VDAC patterns even months after the first learning phase. However, as you may have noticed from the description, VDAC paradigms can be quite involved, and designing VDAC experiments requires researchers to keep track of many fine details, such as the colors and shapes of targets versus distractors, as well as how frequently participants see the previously rewarding colors during the test phase.

Scientists have typically assumed these details don’t individually matter in whether or not VDAC paradigms work, but this assumption has not been tested until a recent study by Milner, MacLean, and Giesbrecht, “The persistence of value-driven attention capture is task-dependent,” which was published in Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. In five experiments, the authors meticulously break down different components of typical VDAC studies to test how each component contributes to whether or not VDAC effects happen at all and how long they last when they do.

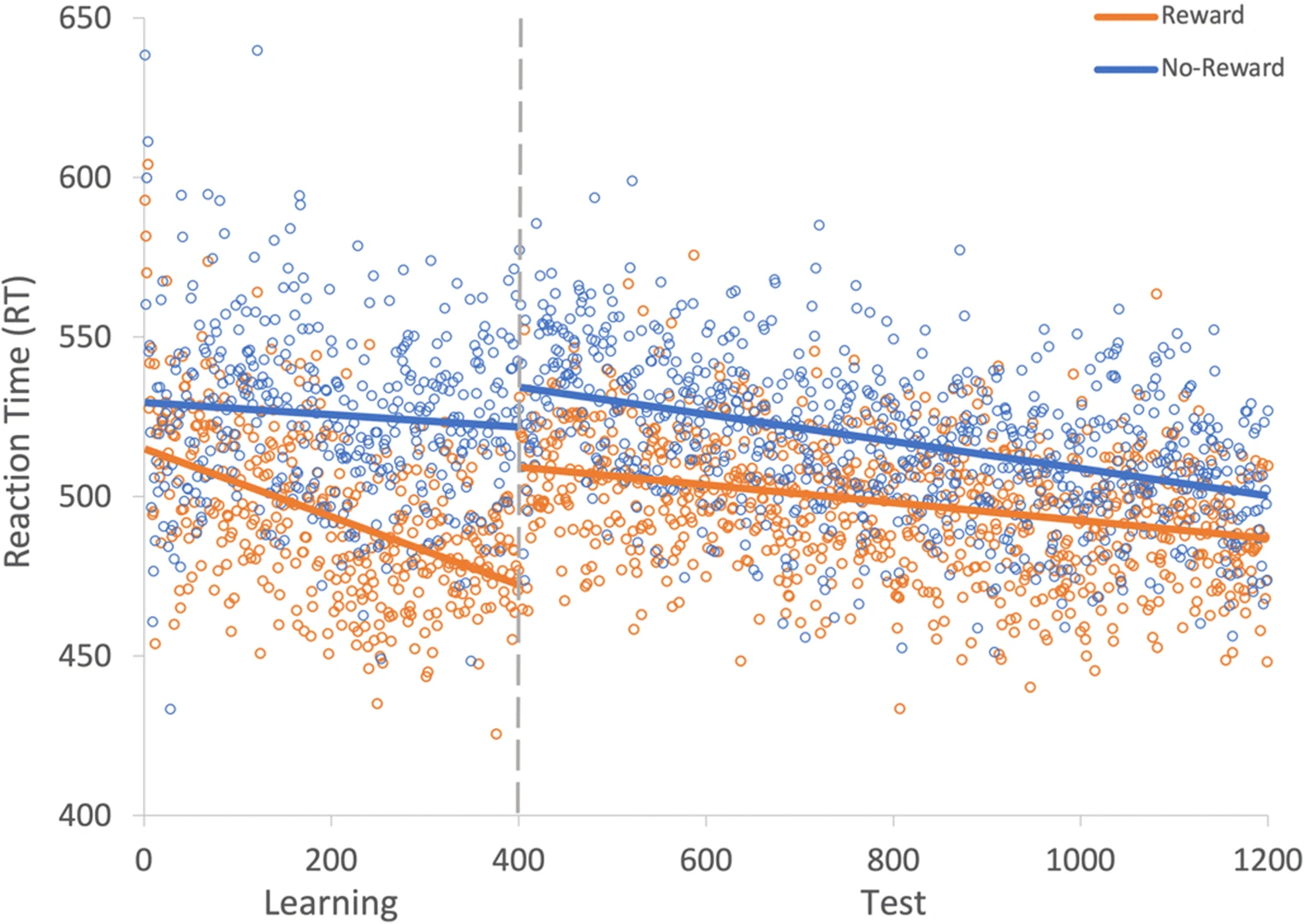

Their first experiment tested whether they could observe persistent effects of a learned reward association. To this end, participants learned to associate either red or blue circles with rewards during the learning phase by frequently being rewarded with more cash when they correctly indicated whether the line inside was vertical or horizontal. In the test phase one week later, they completed the exact same task, except that they were no longer rewarded for accurate answers. The important manipulation here is that the color associated with reward was still relevant to the task during the test phase—that is, participants still had to pay attention to red and blue circles, even though they were no longer rewarding.

The results showed that the reward association between red or blue circles persisted even after one week. In the test phase, participants were faster to respond to the color that they’d previously learned to associate with a reward than to the color that had not been associated with a reward. This assured the authors that reward associations could indeed persist for as long as a week, at least when the feature was relevant to the task, and from there the authors began to individually test how different aspects of traditional VDAC studies then influenced VDAC effect patterns.

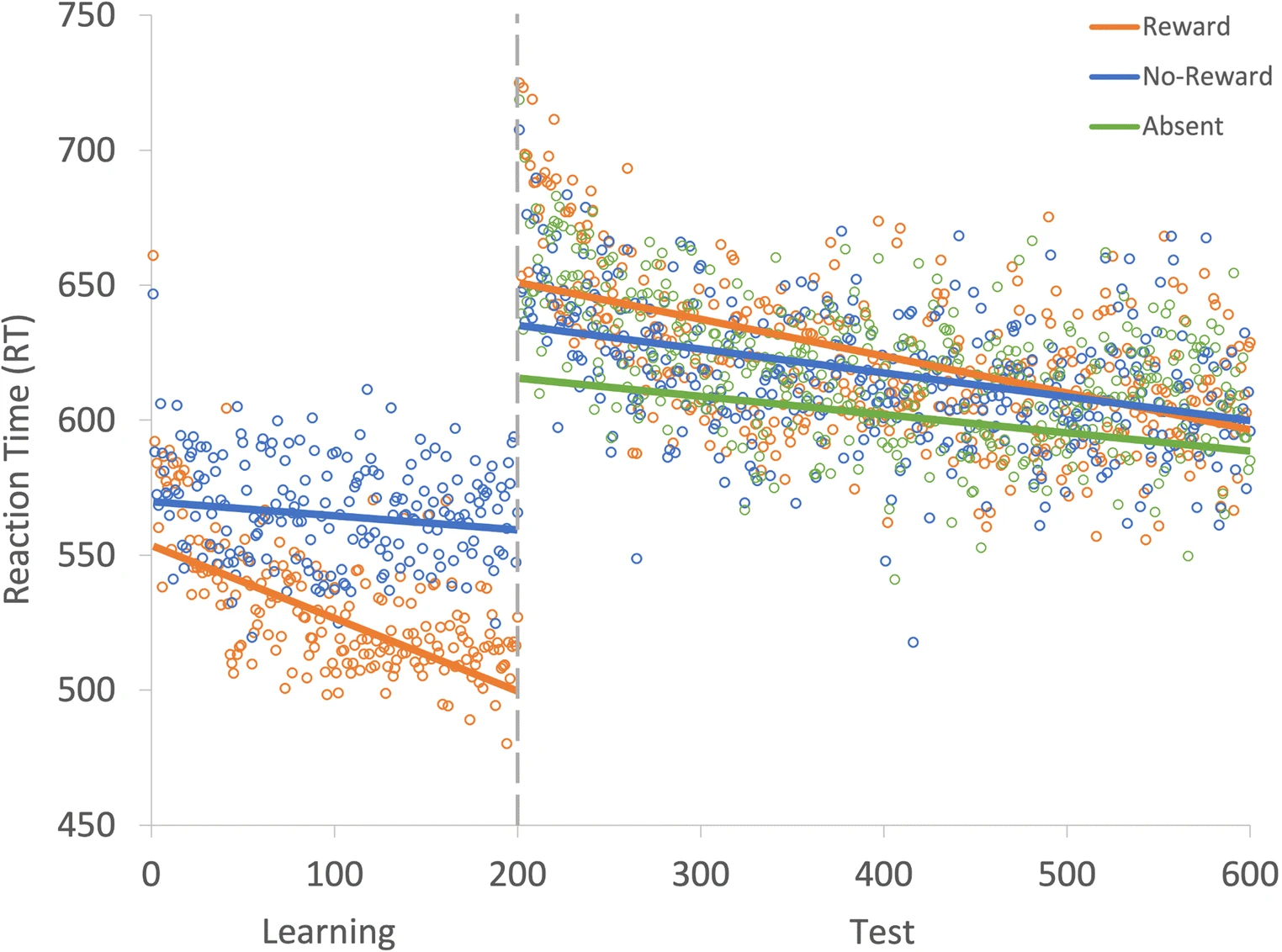

In their next three experiments, the authors tested the influence of three different features of traditional VDAC studies. In one, they tested the effect of changing the target colors between the learning and test phases, so that participants learned a reward association with red or blue but then had to pay attention to green or orange circles (and then try to ignore the red and blue distractors). In another experiment, they tested the effect of changing the shape of the targets from a circle in the learning phase to a diamond in the test phase, which would make the target more “visually salient”, or obvious, while once again red and blue circles served as distractors. In yet another experiment, they sometimes removed the red and blue distractors from the test phase display to see if fewer exposures to distractors helped VDAC effects last longer.

To their great surprise, they found that none of the individual features of traditional VDAC studies could elicit VDAC effects by themselves. It was only when they combined all of these manipulations into their final experiment, where test phase targets were a different shape and color than learning phase targets, and only some of the test phase displays had distractors with the formerly-rewarding colors, that they finally observed slower reaction times to displays with these previously-rewarding distractors.

The authors came away with some important conclusions about VDAC studies. First, observing VDAC effects depends on the design of the VDAC paradigm, and a VDAC experiment may require all, and not just some, of the design features from the authors’ final experiment in order to elicit VDAC effects. Even then, VDAC effects may not be as persistent as the field believes, since the authors saw the VDAC effects weakening over the course of the test phase.

Cognitive psychologists may therefore need to be extra careful when they design future VDAC studies. Although this may seem like a bit of a setback, I’m sure there is still much to be learned from this particular paradigm about the influence of experience on attention. After all, it’s what always encourages scientists to return to the proverbial leaf pile: the reward of discovery.

Featured Psychonomic Society article

Milner, A.E., MacLean, M.H. & Giesbrecht, B. (2023). The persistence of value-driven attention capture is task-dependent. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 85, 315–341. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-022-02621-0