Are your decisions tied to your gender? Prior research has shown gender differences in financial and career-related decisions, like choosing what to invest in or entrepreneurship. Research has suggested that this may be related to the greater risk sensitivity in women compared to men. But is this true in all situations?

“Do men and women think differently about uncertain financial decisions? This research suggests the answer is no…and yes,”

says Uma Karmarkar (pictured below), the author of an article recently published in the Psychonomic Society’s journal Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience.

In this study, two groups of men and women completed several rounds of a decision-making game known as the “Pro/Con task,” depicted in the image below.

Here’s how the game works. During each round, you’ll draw a poker chip from a bag that contains 100 red and blue poker chips. If you draw a red chip, you’ll win $20, but if you draw a blue chip, you get nothing. But there’s a catch. You start the game with $10 and you can use this money to buy tickets to play the game. Each round, you have to decide how much you are willing to pay for your ticket. Before you decide if you want to play that round, you receive some information about what’s in the bag, like “There are at least 25 red chips and at least 30 blue chips in the bag.” So, will you buy a ticket?

This task is unique from other decision-making games in two ways. First, it is a game of ambiguity, not risk. If you knew exactly how many chips of each color were in the bag (say, 34 red chips and 66 blue chips), then your decision is based on how willing you are to take a risk. Previous research has shown that men tend to be less risk-averse than women. However, the Pro/Con game gives you only partial information – so rather than how willing you are to take risks when you know your chances, this game tests how willing you are to gamble when you aren’t sure about your real chance. Previous research has been mixed regarding gender differences in this kind of ambiguity sensitivity, though one large-scale study of ambiguity attitudes found no effects of gender. It’s still unclear if gender plays a role in ambiguity like it does in risk, and if it does, then how.

This task also separately varies the types of information that you receive before making your decision to play or not. Knowing how many red chips are in the bag is favorable towards a winning outcome, while knowing how many blue chips are in the bag is unfavorable. The previous research on ambiguity during decision-making primarily focused on how much information was unknown, but the Pro/Con task considers how people use the partial information that they do know.

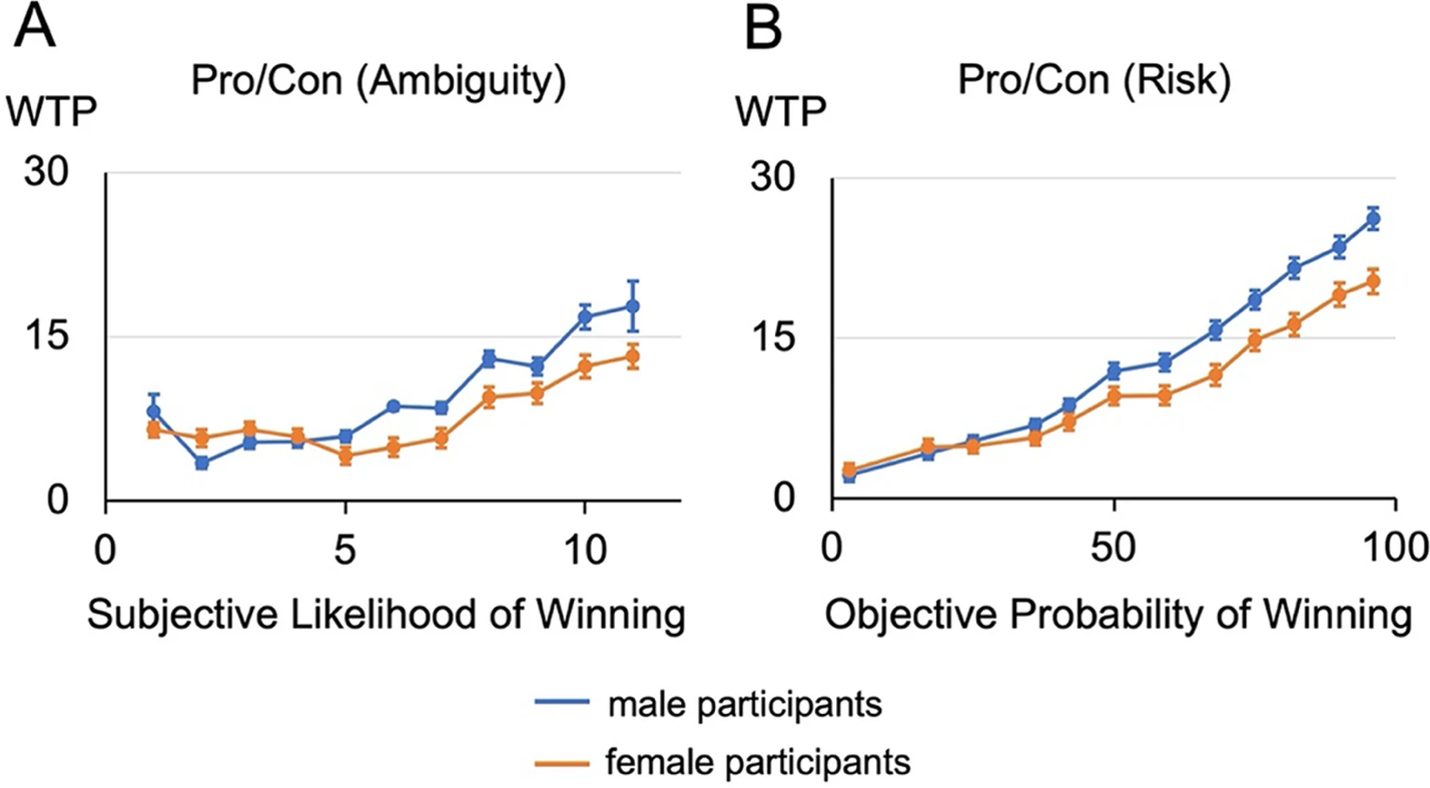

In the first experiment, when more favorable information was known (that is, when a larger number of red chips was revealed), people were willing to pay more money for a ticket, and the reverse was true for unfavorable information (when more blue chips were revealed), as you might expect. While men and women were willing to pay similar amounts to play generally, men were more influenced as the amount of favorable information increased. As the total information increased (the total number of red chips and blue chips revealed), and the decisions became more risk-like, men were willing to pay more to play than women.

The second experiment was similar to the first but included a version of the game that only relied on risk. In this version, participants were told the exact contents of the bag (30 red chips and 70 blue chips), reducing the ambiguity to zero. The results of this experiment, pictured below, were like the first: as the likelihood of winning increased, men were willing to pay more money to play than women.

According to Karmarkar,

“This suggests that regardless of whether the risk is exogenously presented objectively or endogenously estimated subjectively, male participants significantly increase their WTP [willingness to pay] more than female participants as the perceived likelihood of winning increases.”

How was the risk estimated subjectively? Karmarkar also looked at how gender affected the perceived likelihood of winning and subsequent decision-making. During the game, the participants were asked to estimate which color chip they thought would be pulled, from “definitely red” to “definitely blue.” For men, revealing more red chips corresponded with larger estimates of the likelihood of winning. This “optimism bias” might drive gender differences in decision-making during ambiguous situations. Regarding the findings, Karmarkar said,

“When there’s very little information about the situation, men and women respond quite similarly. But men appear to have an optimistic bias – the more information you add, the more they interpret it as leading to a rewarding outcome, and the more they’re willing to invest.”

While pulling a red chip has little real-world impact, risk and ambiguity sensitivity play a major role in financial and career-related decisions, like investment portfolios, retirement, and entrepreneurship. When making these kinds of decisions, more information is better, but how we use that information might be the driving force behind gender differences.

Featured Psychonomic Society article:

Karmarkar, U. R. (2023). Gender differences in “optimistic” information processing in uncertain decisions. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-023-01075-7