Have you ever had a conversation with someone who constantly averted their gaze? Why do you think that is? If you are like most people, you might suspect a myriad of reasons, with most being categorically not good.

You might suspect that your conversational partner is socially uncomfortable, disinterested in the conversation, hiding something, or maybe even lying. But what if they were only looking away to help jog their memory for specific information?

When trying to recall verbal information from memory, people often look to the location where that information was visually encoded even if the visual stimulus is no longer there. This behavior is known as the ‘eye movements to nothing’ (or looking to nothing) phenomenon.

For instance, imagine that a professor displayed the definition of the ‘eye movements to nothing’ phenomenon on the left side of a screen during a lecture. During a pop quiz, a student might look to the left side of the screen to recall the definition, even if the professor has already moved on to a new slide and the definition is no longer presented.

Past research shows that people often look to the location where information was studied to aid retrieval of the information. This behavior is more often observed when people correctly recall the studied information, relative to incorrect recall – suggesting a clear link between ‘looking at nothing’ and memory retrieval.

The question that remains is what is the cognitive relationship between looking at nothing and verbal memory?

In a recent article published in the Psychonomic Society’s journal Memory and Cognition, researchers Agnes Scholz, Anja Klichowicz, and Josef Krems investigated the mechanisms underlying the eye movements to nothing phenomenon. More specifically, they tested whether covert (along with overt) shifts of attention could explain the impact of ‘eye movements to nothing’ on verbal memory.

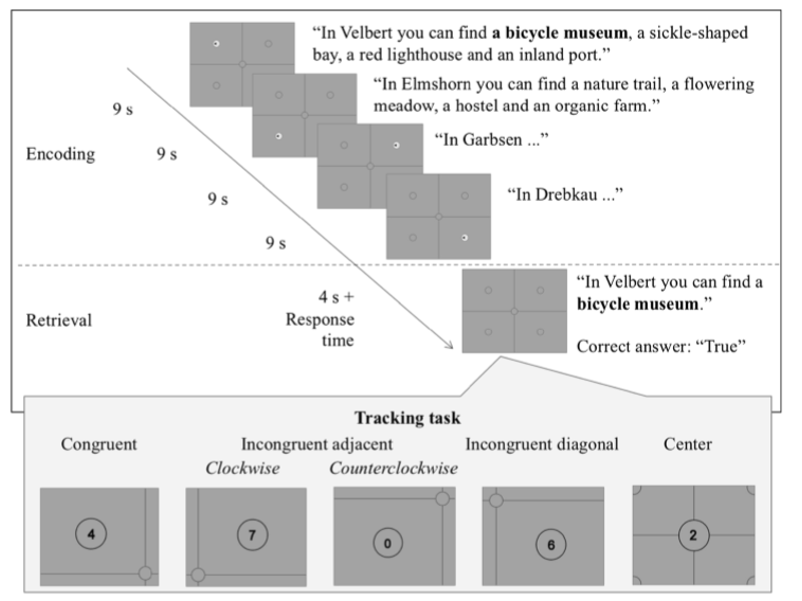

To test the role of attention, the researchers conducted a memory and eye-tracking experiment that consisted of two phases: a study phase and a retrieval phase (see figure below).

During study, participants listened to four sentences one at a time and were instructed to memorize the content to the best of their ability. As each sentence was played, a symbol appeared in an associated location on the computer screen.

During retrieval, participants solved an unrelated visual tracking task which required them to press a button on the keyboard as quickly as possible each time a digit was presented on the screen. Importantly, the digits appeared either in the associated location of the study sentence, in an adjacent location, in a diagonal location, or in the center of the screen. Simultaneously, participants were asked a series of true or false questions regarding the study sentence (memory test).

Participants were either instructed to move their eyes freely throughout the task, but keep their eyes on the screen (overt eye movement group), or to keep their eyes fixated on the center of the screen and covertly shift their attention to the digits during the visual task (attention shift group). Also, the tracking task either appeared in the congruent location, incongruent adjacent location, incongruent diagonal location, or in the center of the screen (baseline) in both instruction conditions.

Given the hypothesis that covert shifts of attention could lead to high retrieval accuracy, the researchers predicted that response accuracy would be equally good for the overt eye movement group and the attention shift group. The researchers also predicted greater response accuracy for the participants who were guided toward the location associated with the study information (congruent condition) relative to incongruent locations (adjacent or diagonal).

To measure performance in retrieval accuracy, the researchers calculated the mean percentage of correct responses on the true/false statements for each of the tracking task conditions (congruent, incongruent adjacent, incongruent diagonal, and center). Since there was no study sentence associated with the center location, but participants still performed the tracking task at this location, retrieval performance at the center location was treated as a baseline to which accuracy in all other conditions was compared.

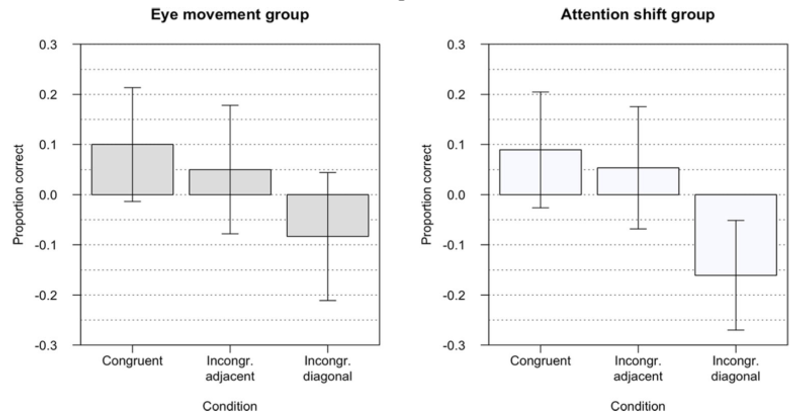

Relative to baseline, there was no difference in retrieval accuracy between the two instruction groups. In the figure below, this is evidenced by similar bar heights between the two graphs for each comparable condition. However, within each group, there was a difference based on the visual task location, such that accuracy (relative to baseline) was greatest for the congruent location, followed by the incongruent adjacent location, and then the incongruent diagonal location. In the figure below, these results corresponds to a positive mean difference in accuracy between congruent and baseline and incongruent adjacent and baseline, but a negative mean difference between incongruent diagonal and baseline. This pattern was observed in both graphs.

Based on the results of the experiment, it is clear that covert shifts of attention can lead to good memory retrieval. But how do covert shifts of attention compare to overt shifts? Given that participants in the eye movement group were not explicitly instructed to look at the digits in the tracking task, they could still have used covert attention shifts. This might explain the absence of differences in accuracy between instruction groups.

Based on the results of the experiment, it is clear that covert shifts of attention can lead to good memory retrieval. But how do covert shifts of attention compare to overt shifts? Given that participants in the eye movement group were not explicitly instructed to look at the digits in the tracking task, they could still have used covert attention shifts. This might explain the absence of differences in accuracy between instruction groups.

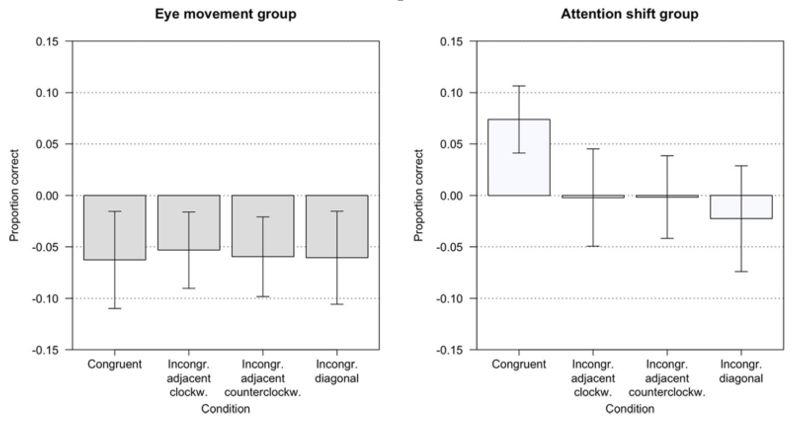

Therefore, in a follow up experiment, participants in the eye movement group were explicitly instructed to look at the digits in the tracking task. Surprisingly, the benefit of the congruent location (relative to baseline) went away when the explicit instructions were given. In fact, there was no significant difference in accuracy for any of the locations relative to baseline. In other words, overt eye movements to the associated study location resulted in decreased retrieval accuracy relative to covert eye movements (see figure below).

The finding of decreased accuracy in the eye movement group under explicit instructions to look at the digits in the tracking task was surprising. However, the researchers argued that this finding was consistent with studies in working memory. Previous work has shown that directly looking at an object leads to automatic encoding of that object. Automatically encoding a secondary object via eye movements led to impaired memory for target objects potentially due to competition for memory resources. The tracking task did not require participants to encode the digits, only to detect them. Thus, there was no impairment in memory due to covert detection of the digits (free gaze condition). However, when participants were asked to explicitly look at the digits, this may have led to automatically encoding the digits and thus impairing memory.

So the moral of the story, is maybe we should give individuals with ‘wandering eyes’ the benefit of the doubt. Sure, they could be socially awkward or out to deceive us when looking at nothing, but maybe they could just be trying to remember what was said.

Featured Psychonomic Society article:

Scholz, A., Klichowicz, A., & Krems, J. F. (2017). Covert shifts of attention can account for the functional role of ‘eye movements to nothing’. Memory and Cognition, DOI 10.3758/s13421-017-0760-x.