One of life’s most difficult challenges is keeping information a secret, even when well-intentioned. Imagine you need to plan a surprise party for your dad. You send out the invitations, order a cake, and buy the decorations. When you’re talking over these details with your brother, he suddenly looks toward the door. Naturally, you look over there as well to see (who else) but your dad standing in the doorway. You quickly switch the subject and hope he didn’t hear you. This scenario, a perennial favorite of TV show writers (in the form of the “he’s right behind me, isn’t he?” trope), is something many of us are all too familiar with.

But behind this anecdote is an important element of human behavior: we tend to shift our attention, and our eyes, to wherever other people are looking. When your brother looks towards the door, your instinct is to look there as well. This behavior underlies a lot of our social interactions and is central to our ability to interact with other people, for example, by helping us keep surprises secret (at least some of the time).

But how automatic is this effect? Let’s say you’re trying to pretend you didn’t notice your dad in the doorway. Do we reflexively look where other people do, or can we override this behavior? In a paper published in a Psychonomic Society journal, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, Mario Dalmaso, Luigi Castelli, Giovanni Galfano (pictured below) set out to answer this question by measuring eye movements in the presence of these gaze direction cues.

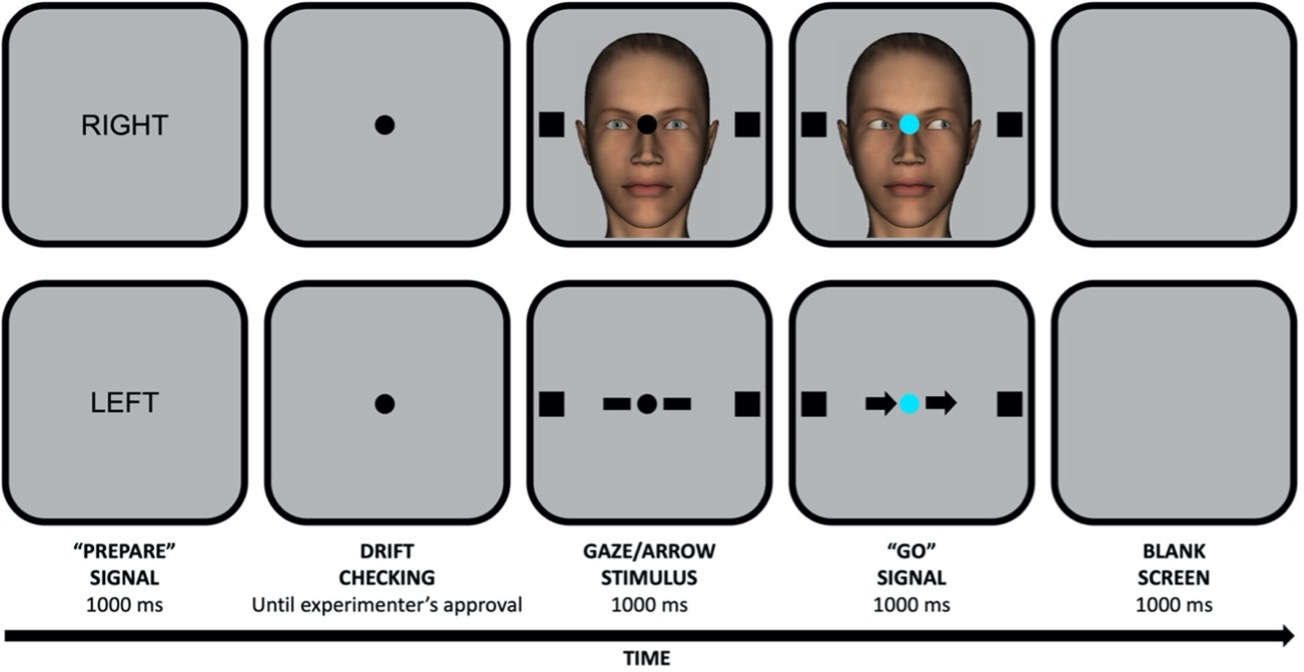

In their experiments, participants viewed displays (like the one below), where they were instructed to move their eyes to one of two squares, either on the left or the right side of the screen. In the middle of the display was an image of a face. Half of the time, the gaze direction of the face matched the direction they were instructed to follow, while the other half of the time, the face was looking in the opposite direction.

There’s no incentive for participants to follow the direction of the person’s gaze since it’s irrelevant to the task. Still, people are faster to move their eyes (i.e., make a rapid eye movement, or a saccade) when the gaze direction of the face matches the direction of their planned eye movement, compared to when it does not match. In other words, you are slower when the face is looking to the left and you want to move your eyes to the right. (Think of it as a version of the Stroop task, but for your eyes).

To test whether you can override this behavior, the authors introduced a key element in this study: they added a delay between the time that subjects were given the instruction and when they moved their eyes. Participants were instructed to plan their eye movement in one direction, but then had to wait more than two seconds until they were given a “go” signal to actually move their eyes. In this case, participants had plenty of time to prepare the eye movement in the intended direction (for example, to the right). But even with this advanced planning, they were still slower when the gaze direction of the face was opposite to their planned eye movement (e.g., to the left).

So what does this mean for gaze behavior? Our tendency to look in the same direction as other people is fairly automatic, and difficult to override. Even when you’ve prepared to move your eyes in one direction, seeing another person look elsewhere can slow you down. You may have a hard time pretending you didn’t notice your dad in the doorway if your brother looks there first. Or, if you and your friend are stuck listening to a boring story, and they start looking around, you may have a hard time looking interested too. Ultimately, our tendency to follow another person’s gaze generally serves us well– if somebody is looking at something, it’s probably important to you too!

Featured Psychonomic Society article

Dalmaso, M., Castelli, L., & Galfano, G. (2020). Early saccade planning cannot override oculomotor interference elicited by gaze and arrow distractors. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 27(5), 990-997. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-020-01768-x