Who would have thought that by June 2020 we would have encountered as many crises as there were months?

January: #WW3 predicted as tensions rise between the US and Iran

February: #Australian wildfires ablaze

March: #WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic

April: #Global economies plunge

May: #BLM Black lives matter protests

June: #Locust swarm

While COVID-19 seems to be fluctuating under different measures around the world, racial tensions skyrocketed in the US following the death of George Floyd, a Black man, at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, a White man. This event led to daily protests across the US and became a global movement as citizens of cities such as London, Brussels, Seoul, Sydney, and Rio de Janeiro protested in solidarity and for their own reforms.

How do categorization training and facial identity apply to the current societal woes?

Let’s begin with the cross-race effect. This is the well-documented phenomenon that people are better at recognizing members of the race with which they are familiar (especially people of their own race) than individuals of other, less familiar races. This effect holds up with all types of populations and methodological considerations and appears to begin during the first six months of life. Many researchers currently believe that this effect is a product of both innate facial processing biases and socio-cognitive experiences, namely familiarity with individuals with different facial features and characteristics.

Recognizing well-known individuals from upright images happens quickly and fairly easily. Do you recognize the individuals in the inverted images below?

Did Adele (left) and Barack Obama (right) quickly come to mind? These faces may be a little harder to recognize. Most of us have more difficulty recognizing inverted images than upright images without training.

Familiarity with one’s own group (i.e., biological race or adopted race) and unfamiliarity with different groups (i.e., a different race from the biological race or adopted race) may create an “us vs. them” dichotomy in thinking and has consequences on perceptions about a person or a group of people. One’s experience can influence the accuracy and time it takes to recognize faces as well as judgments about competence, attractiveness, or emotional expressions. This “in-group, out-group” thinking is another possible driver of prejudice, racism, and discrimination.

Fabian Soto (pictured below) explored the perceptual effects of discriminating between unfamiliar faces following the categorization training of certain features in a 2019 article published in the Psychonomic Society journal, Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics.

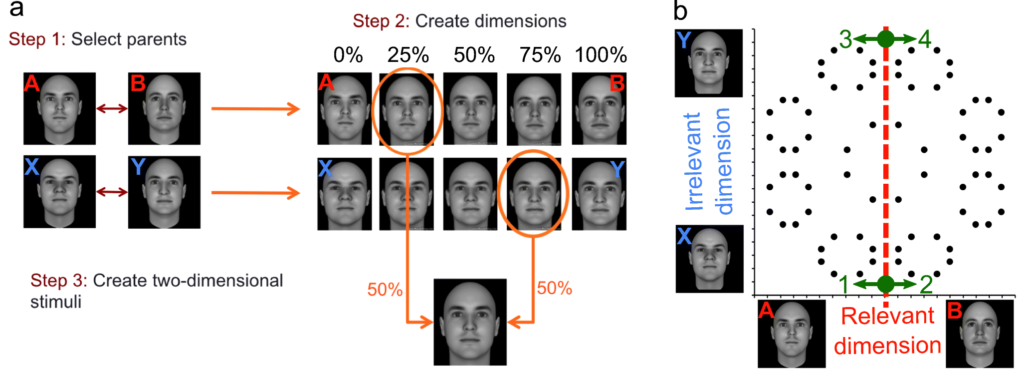

Soto used computer-generated “parent” images, shown in Panel a, Step 1 in the graphic below, to create two sets of morphed images that varied by the percentage of parent represented (as shown in Panel a, Step 2 in the graphic below). The reasoning is that before any categorization training, we will encode and store a template of the face they have encountered. Depending on exposure to a parent face, we can discriminate between faces that share characteristics of the original template, or parent face, and faces that do not share the same characteristics.

To test whether irrelevant characteristics are included in the template during categorization training, a set of test stimuli were created using different combinations of parent images with A and B comprising one dimension (relevant features) and X and Y comprising another dimension (irrelevant features), as shown in Panel b in the graphic above of “morphing space”. The green points in Panel b are basically neutral morphed images of the relevant parent images (AB) that differ in their irrelevant parent images characteristics. Moving in the direction of the arrows produces images that utilize more or less information from the parent images.

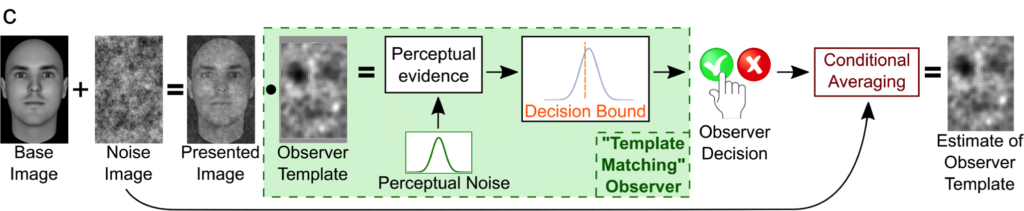

The first part of the task was to complete a “reverse correlation trial” task, as shown in Panel c in the image below, in which participants had to determine if one of two images (varied based on the amount of ambiguity or noise was present) belonged to parent A or Parent B. The results of this task indicated the participants were able to reliably indicate images that had been obscured as belonging to the correct parent image.

The second, and more important, part of the task was the categorization training, in which participants were given practice with one of the morphed variations between parents A and B and parents X and Y (the black points in panel B above). The practice consisted of one image (a black point representation) that was categorized as belonging to parent A or B. Characteristics from parent X and Y were considered irrelevant to the task and participants were not asked to categorize stimuli for X or Y. The key test was how would the participants categorize the second set of stimuli during “reverse correlation trials” after the categorization training.

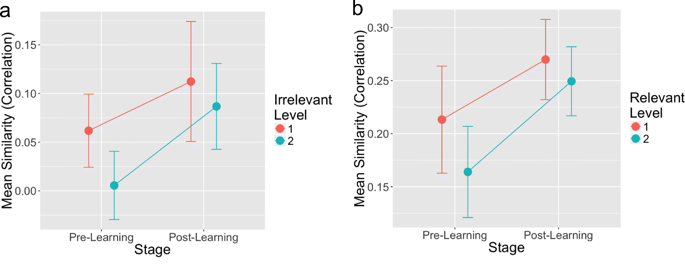

Soto found that the participants responded differently to the second set of reverse correlation trials after the categorization training. As seen in the figure below, correlations were higher after training with a trend indicating that participants were able to discriminate between the extreme dimensions of parent A and parent B regardless of irrelevant details from parent X or Y (Panel a). When irrelevant stimuli were included in the template, participants displayed a higher level of invariance (i.e., discriminated faces using similar information) across changes in the irrelevant dimension (Panel b).

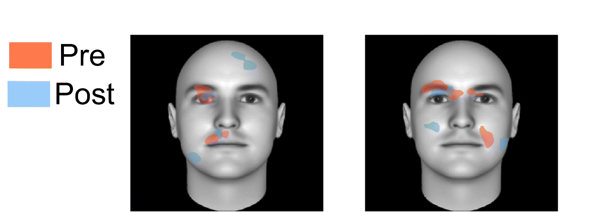

This finding is best seen in the plot below showing what details, on average, were used before categorization training (as represented with the red blobs) and ultimately by the participants after categorization training (as represented with the blue blobs). Although there seems to be a convergence of the information within the internal features of the face, such as the eyes, it may simply be that the categorization training allows the participants to become less responsive to differences in features that may not matter to facial discrimination or categories, and their internal templates are modified through that experience.

This study highlights the importance of experience and modification of internal perceptual templates, which can influence an individual’s perception of different stimuli. If facial discrimination is modifiable with categorization training that uses ambiguous or masked stimuli and the cross-race effect can be eliminated with training or immersion, perhaps a concerted effort at various levels of society (schools, law enforcement, human resource training, etc.) could implement similar training or familiarization techniques. Maybe such training could begin to mitigate tensions that exist between different groups by reducing biases based on physical differences.

These questions barely scratch the surface of a critical topic. As scientists and consumers of science, we know that science can help direct change. As cognitive psychologists, we know games can be a great way to deliver that change.

Psychonomics article focused on in this post:

Soto, F. A. (2019). Categorization training changes the visual representation of face identity. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 81, 1220–1227. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-019-01765-w