If you witness a crime, you may be asked to try to pick the perpetrator out of a police lineup. If you are unfamiliar with this line of research or have never been an eyewitness, your notion of a lineup may have come from movies and tv, and may be something like this:

(Warning: watching this video will give you an unshakeable, and possibly regrettable, ear worm.)

A lineup contains one suspect – who is innocent or guilty – and many fillers. Unlike in the clip, the police typically do not administer live lineups. More commonly, they show eyewitnesses photo lineups (in the US, for example) or video lineups (in the UK, for example). Also unlike in the clip, the fillers physically resemble the suspect or description of the perpetrator. For example, if the perpetrator was described as having dark skin tone, all members in the lineup should have dark skin tone.

A well-known phenomenon that has been discovered in research on identification from lineups is a reduced ability to recognise people of different races relative to those of the same race, known as the cross-race effect or own-race bias. This blog has touched on this issue before.

How does this phenomenon play out in the court of law?

Trace back the literature on eyewitness identification research and you will see an evolution of thinking about eyewitness expressions of confidence. Until recently, conventional wisdom held that confidence was not diagnostic of accuracy. Therefore, recommendations given to the police and courts were to discount witnesses’ confidence.

That belief has taken an about face. Today there is a general consensus among eyewitness memory researchers that confidence is diagnostic of accuracy in the identification. Critically, this applies only to the initial identification – that is, the level of confidence given when the suspect was first picked out of the lineup, not the one given much later in the court of law. Today recommendations given to the police and courts is to take initial confidence into account.

This type of confidence (the confidence expressed at the initial identification) is referred to as postdictive confidence.

Another type of confidence is referred to as predictive confidence. When a witness is reporting a crime, well before the police have a suspect, it is not uncommon for the police to ask a witness about the presumed chances that he/she would be able to identify the perpetrator. Much less is known about whether predictive confidence is also highly diagnostic of accuracy.

A recent article published in the Psychonomic Society’s journal Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications targeted the issue of predictive vs. postdictive confidence and the other-race effect. Specifically, researchers Thao Nguyen, Erica Abed, and Kathy Pezdek addressed these main questions:

1. a) How diagnostic are expressions of immediate vs. delayed predictive confidence?

1. b) Is the diagnosticity of immediate vs. delayed predictive confidence affected by the cross-race effect?

2. a) How diagnostic are expressions of postdictive confidence?

2. b) Is the diagnosticity of postdictive confidence affected by the cross-race effect?

In two experiments (one a direct replication of the other), participants were assigned to an immediate or a delayed condition. Participants were White and they all studied 20 faces – half Black and half White. After each face was presented, a predictive confidence judgment was given either immediately after presentation (immediate condition) or 30 seconds after presentation (delayed condition).

All participants were tested on 40 faces – half Black and half White; 20 were shown during the study phase and 20 were not.

Here are examples of the study phase for both conditions:

Immediate condition:

Delayed condition:

Here is an example of the test phase:

What did Nguyen and colleagues find?

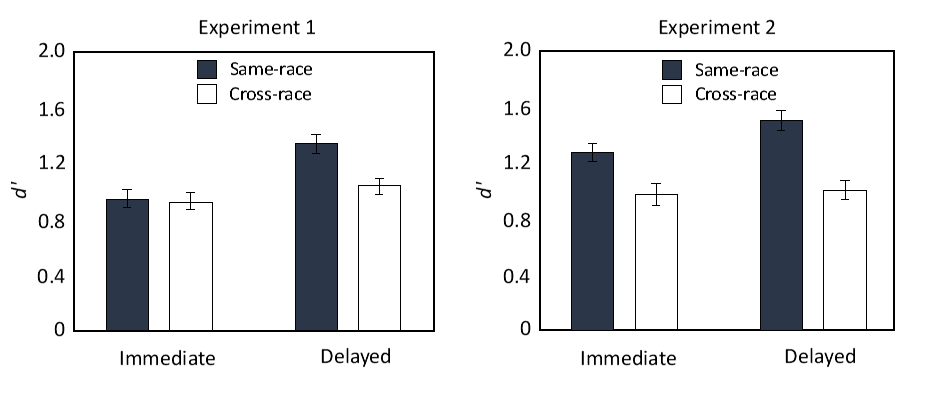

Before considering the main results, it is important to see if the cross-race effect replicated. It did, as shown in the figures below:

Discriminability, measured by d’, was higher in the same-race vs. cross-race stimuli in the immediate and delayed conditions (more so in Experiment 2).

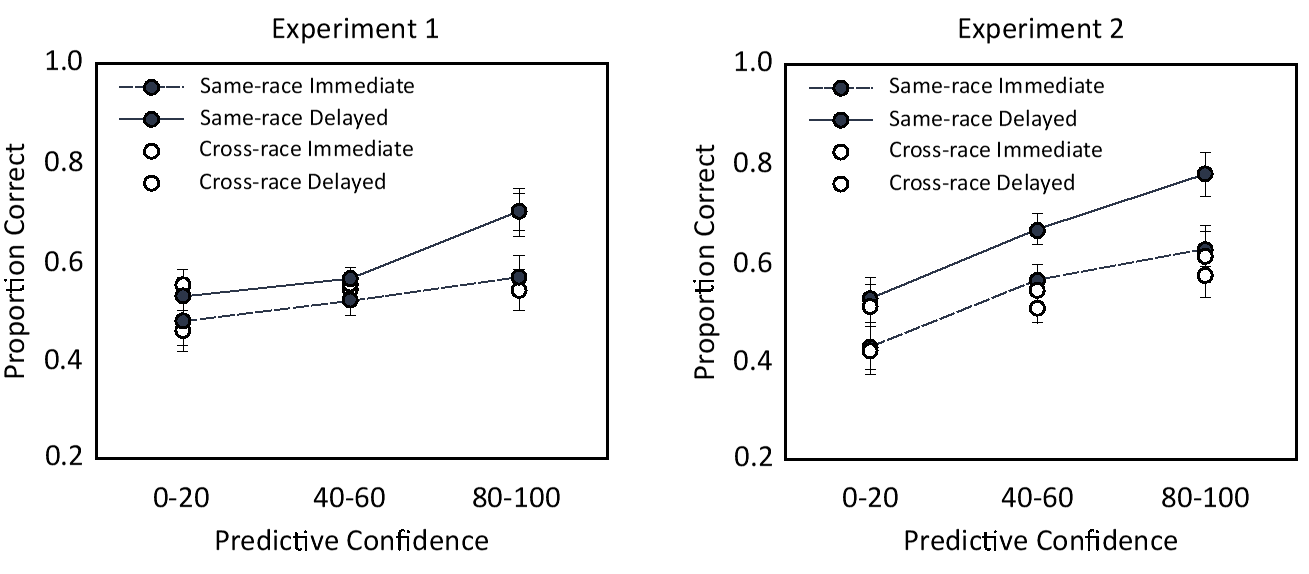

Research question 1: a) How diagnostic are expressions of immediate vs. delayed predictive confidence and b) are they affected by the cross-race effect? The figures below reveal the answers:

The long and the short of it is that predictive confidence is not particularly diagnostic of accuracy for cross- and same-race faces. This is especially the case in the immediate condition.

Put more formally, the authors concluded:

“These results suggest that although delaying JOLs [judgments of learning] allow participants to evaluate their future memory performance more accurately for same- than cross-race faces, nonetheless, the utility of predictive metamemory judgments for estimating subsequent memory accuracy is limited for both same-race and cross-race faces.”

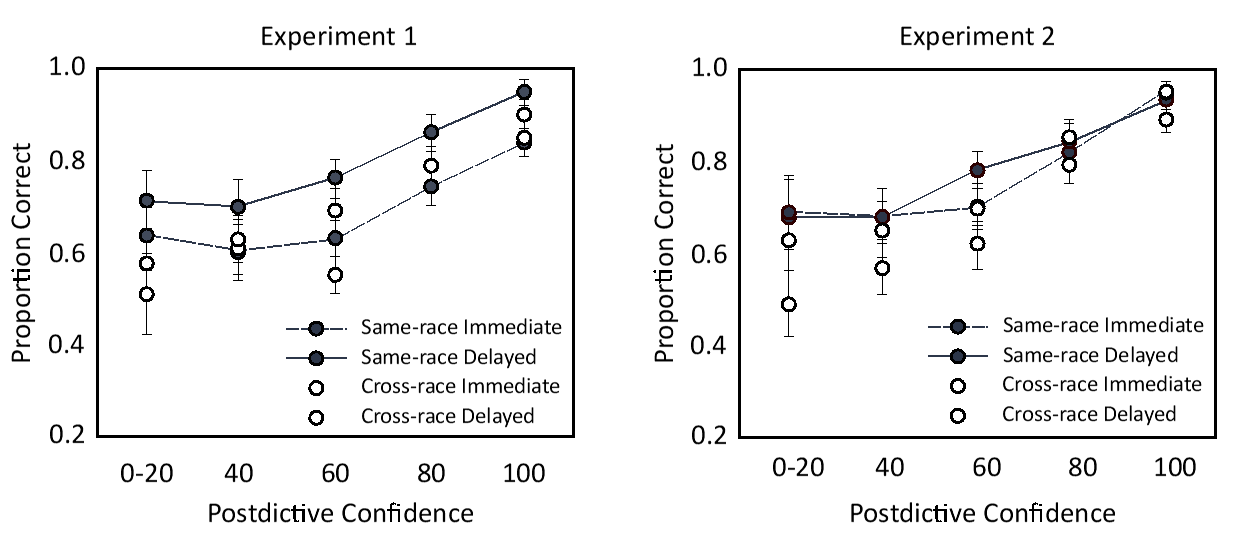

Research question 2: How diagnostic are expressions of postdictive confidence and are they affected by the cross-race effect? The figures below reveal the answers:

The figures show that postdictive confidence is more diagnostic of accuracy. At high levels of confidence, accuracy is pretty high, and it is high regardless of whether the face was the same- or cross- race (and despite the fact that d’ was lower for cross-race faces). And at low levels of confidence, accuracy is lower.

Why these differences between predictive and postdictive confidence arise is presently unknown. The authors suggest, based on results from metamemory experiments, that participants may rely on different information to make their decisions. These findings therefore also add to the literature on metamemory.

It would be surprising if these results did not replicate in a forensically relevant experiment. Nonetheless, a worthwhile effort would be to conduct that experiment, given the important applied implications of the findings by Nguyen and colleagues. In a forensically relevant experiment, instead of studying a list of Black and White faces, the participants would study a video of a mock crime with a Black or White perpetrator, and later memory would be tested on a lineup. In this type of experiment there is only one trial per participant to simulate the experience of a real eyewitness. If the findings replicate – that is, if postdictive confidence were found to be more diagnostic of accuracy than predictive confidence – then this is a message to be passed to those working in the criminal justice sector for two main reasons.

First, asking eyewitnesses the likelihood that they would later be able to recognise the perpetrator or to pick a perpetrator out of a lineup is not that informative. Using predictive confidence as a way to steer the investigation would lead police to invest less time with eyewitnesses who are underconfident and more time with eyewitnesses who are overconfident.

Second, eyewitnesses are less able to discriminate innocent from guilty suspects of other races, but if they do pick out a suspect with high confidence, then the police should focus more of their efforts on investigating that suspect and on ensuring that judges and jurors are aware of the high confidence of the witness.

We can see glimpses of how this plays out in the real world. In a famous case of misidentification, Jennifer Thompson, who is White, identified Ronald Cotton, who is Black, out of a lineup after she reported a crime. He was convicted of that crime and spent over a decade in prison before he was exonerated by DNA evidence. In the first photo lineup procedure, Thompson took 4 to 5 minutes and then tentatively identified Cotton (indicators of low confidence). The investigators ignored her uncertainty at the initial lineup procedure and put more weight on her later identifications. Paying attention to levels of immediate postdictive confidence but not predictive confidence (according to the data by Nyugen and colleagues), and not to the confidence expressed at later identification procedures or at trial, would help prevent innocent people from being wrongfully investigated and convicted.

Psychonomics Fellows may be asked to serve as expert witnesses. And, if the circumstances warrant it, we may be tempted to say that because the witness and suspect are of different races, memory is less trustworthy. Many experts have, in fact, testified to that effect. But based on this research, and other similar research, we should tell the court that while overall memory performance is lower when trying to recognize a person of a different race, initial confidence is an indicator of how accurate the identification is. So, if the witness identified the person out of the initial lineup with high confidence, the court can put weight into that identification. But if a witness identified the person out of the initial lineup with low confidence, the court should not put that much weight into that identification. This is the information that the courts should use to help them make their decisions about the culpability of defendants. This is the information that Ronald Cotton’s jurors should have been given.

Psychonomics article focused on in this post:

Nguyen, T. B., Abed, E., & Pezdek, K. (2018). Postdictive confidence (but not predictive confidence) predicts eyewitness memory accuracy. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications. DOI: 10.1186/s41235-018-0125-4.