How well do you remember detailed visual information, such as the precise color or shape of an object you saw several hours ago? Although intuition might suggest that our memory for fine details is quite poor, research finds that visual long-term memory has a massive capacity for visual details of objects and scenes. For instance, after viewing thousands of individual objects, people can recognize a specific boat or beach scene, even among images of other, previously unseen boats and beaches.

Is this large capacity visual in its nature, or is it related somehow to the objects’ meaning? This was the question Roy Shoval, Nurit Gronau, and Tal Makovski (pictured below) aimed to answer in a paper published in the Psychonomic Society journal Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

Most prior studies have used real-world stimuli (e.g., pictures of boats), which the researchers argue makes it difficult to dissociate semantic from ‘pure’ perceptual factors. To directly assess visual capacity, one needs to test people’s long-term memory for meaningless visual material.

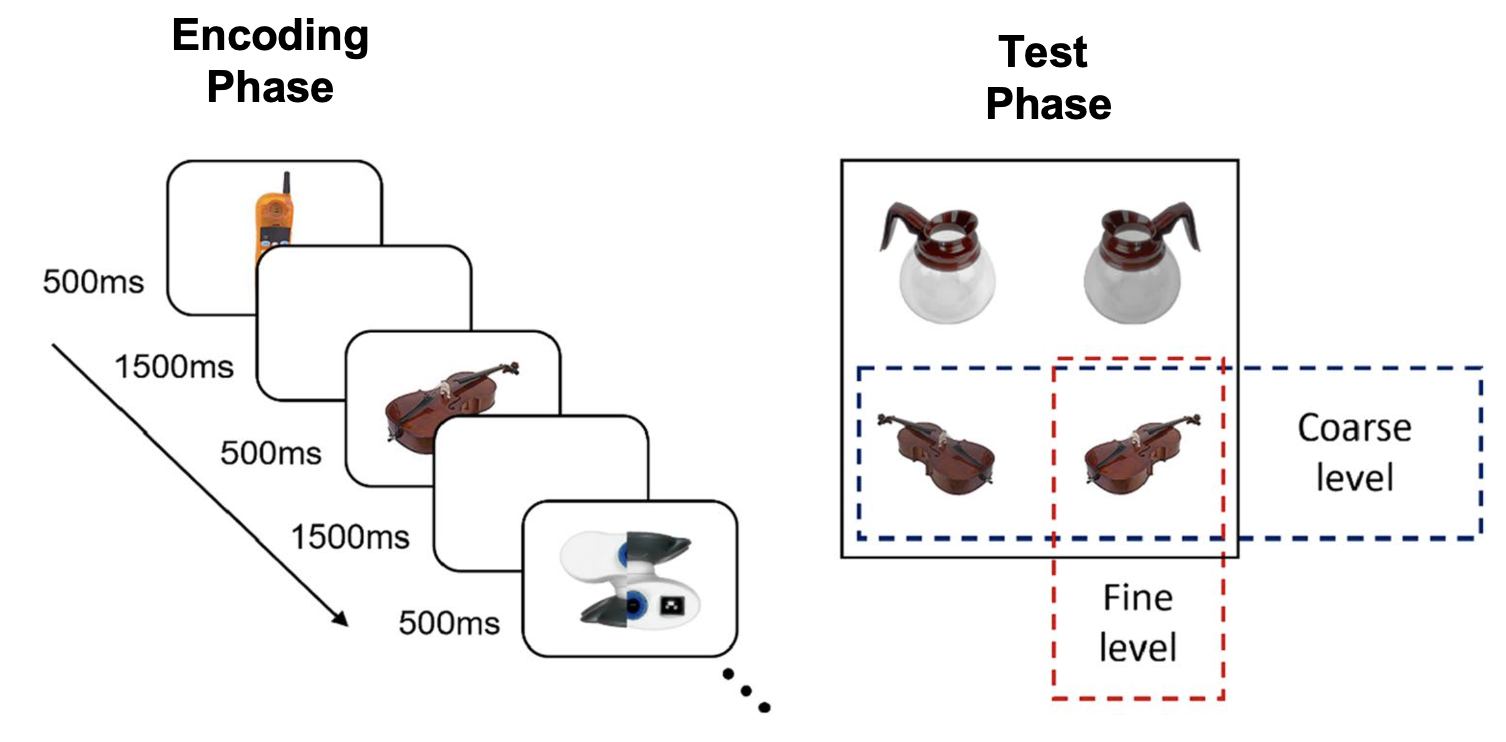

Participants first underwent an encoding phase in which they were presented with over 200 images of real-world objects that were either “meaningful” (i.e., presented intact) or lightly scrambled to make them less meaningful – examples are in the figure below.

Participants then completed a four-alternative forced-choice recognition test on the objects they learned. On each test trial, there were four objects: the object they had seen before (i.e., the correct response) and a new object they had not seen before, as well as the mirror transformations of these objects. Participants were instructed to choose the image they had seen before in its original orientation. A summary of the procedure is provided in the figure below.

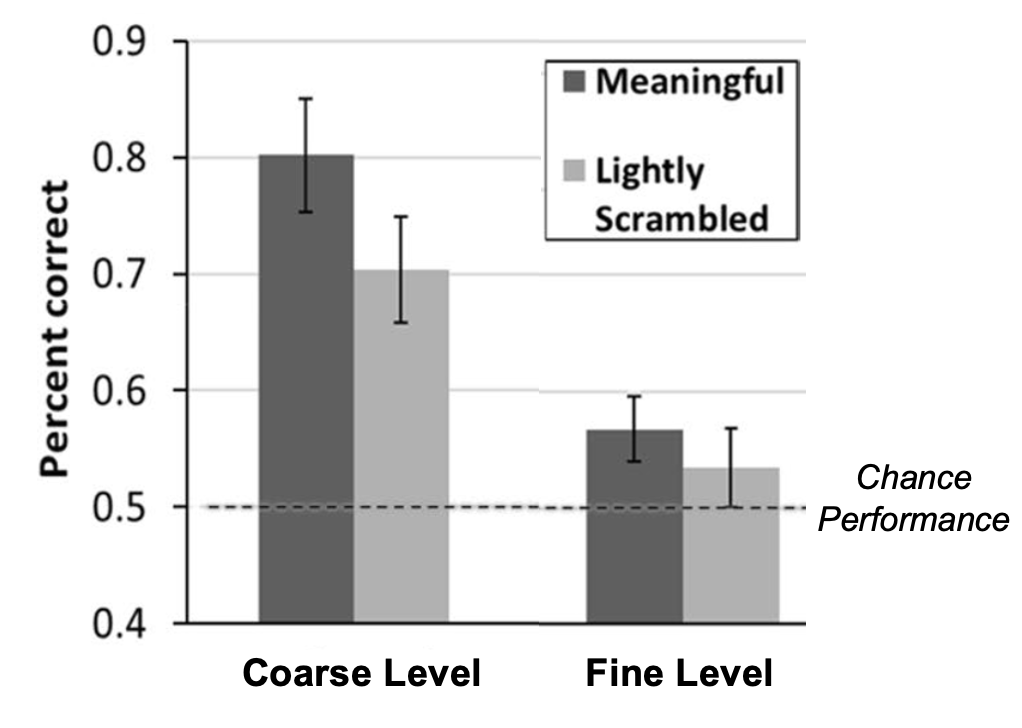

This recognition test allowed researchers to investigate memory for objects at two levels: a coarse level and a fine level. For the coarse level, the researchers analyzed whether participants remembered the identity of previously seen objects, regardless of their orientations. For the fine level, the researchers conducted conditional analyses – if responses were correct at the coarse level, did they also correctly recall the objects’ original orientation? The results are presented in the figure below.

Memory for objects was much better for intact, meaningful than lightly scrambled, less meaningful images! This was especially true at the coarse level.

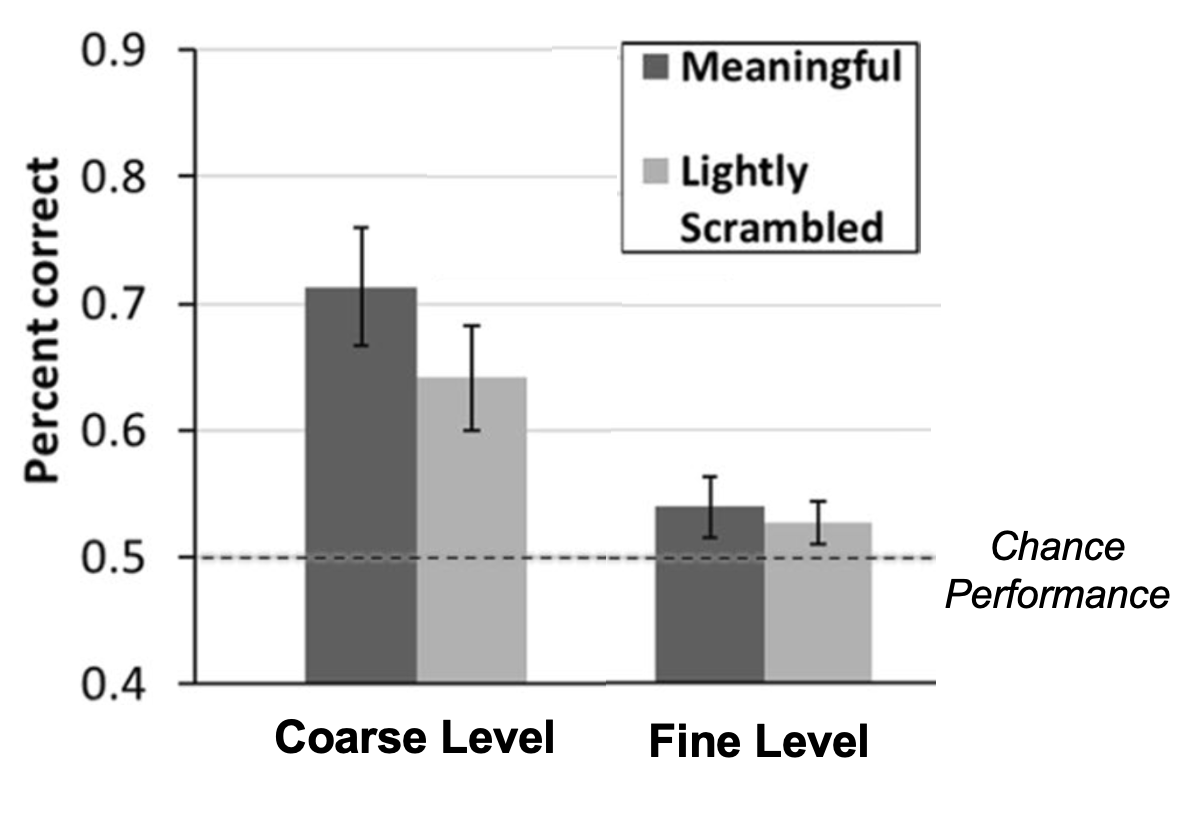

In a second experiment, the researchers decided to really push the limits of long-term visual memory by investigating recognition performance for a large number of images. Thus, the same procedure was used, except participants learned more than 700 objects. As can be seen in the figure below, memory was once again much better for intact, meaningful images than for the less-meaningful, lightly scrambled images.

Finally, in a third experiment, the researchers investigated the capacity of long-term visual memory when the meaning of objects was further minimized. Participants learned over 200 objects that were presented in fully scrambled form (see figure below for examples) and again completed a four-alternative forced-choice recognition test.

In this experiment, memory for objects was only slightly higher than chance – only a handful of the 200+ images were correctly remembered, and memory for visual details was poor.

Taken together, these three experiments find that meaningful pictures of objects are better remembered than scrambled, meaningless versions of the same objects. In fact, visual long-term memory for the meaningless stimuli was shown to be highly limited in capacity. Furthermore, memory for an arbitrary visual detail, such as whether a teapot was facing to the right or to the left, was poor – even for the meaningful objects.

According to Shoval:

“Our findings indicate that our ability to remember pure visual information is far more limited than previously thought, and that a ‘massive’ long-term memory might critically rely on semantic meaning. These findings may be important when attempting to recall a certain sight or event, as well as when serving as an eyewitness to a crime scene.”

Featured Psychonomic Society article

Shoval, R., Gronau, N., & Makovski, T. (2022). Massive visual long-term memory is largely dependent on meaning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-022-02193-y