In all my years of schooling (four years of high school, four years of undergraduate studies, and six years of graduate school), one thing I have never been accused of is PREcrastination. Precrastination, refers to the tendency to hasten engagement in a subgoal at the expense of exerting extra effort.

However, here I report that I was today-years-old when I found out that I am capable of precrastination and you might be too (although precrastination might not always be a good thing). Thus, to precrastinate or not to precrastinate: that is the question.

Take for example the illustration below. Imagine that you are the agent (i.e., the black stick figure near the tree) in this scenario and it is your job to pick up both baseballs and return to your position near the tree.

Think about your action plan for accomplishing this.

Did you mentally pick up the first baseball, bring it back to the second ball, grab the second ball, and return to the tree? If so, you too, my friend, are a pre-crastinator. David Rosenbaum and colleagues (2014) coined the term “precrastination” to refer to the preference of picking up the near object first followed by a further object. This strategy incurs unnecessary additional energy because the agent has to carry the first object away from the goal line (the tree) to the second object and then back. A more optimal strategy in terms of energy expenditure would have been to pick up the further object first, then the nearer object.

One potential reason for choosing the near option first is that doing so might decrease cognitive demand by off-loading working memory as quickly as possible. The idea is that if completing the task requires an individual to hold both objects in working memory, picking up the nearer object decreases this working memory demand more quickly than waiting to pick up the further object first.

Furthermore, if decreasing cognitive demand is the true motivation of precrastination, then a reversal of preference (picking up the further object first) might be observed if there are additional costs associated with picking up the nearer object first, beyond the working memory taxation. For example, individuals might put off picking up the nearer object first if it is significantly heavier than the further object or if carrying the nearer objects requires greater attention and thus cognitive demands, like making sure the contents of the first object do not spill.

To this end, in a recent article in the Psychonomic Society journal, Attention, Perception, and Psychophysics, Lisa Fournier and colleagues conducted two experiments to investigate the tradeoffs between cognitive demands and precrastination.

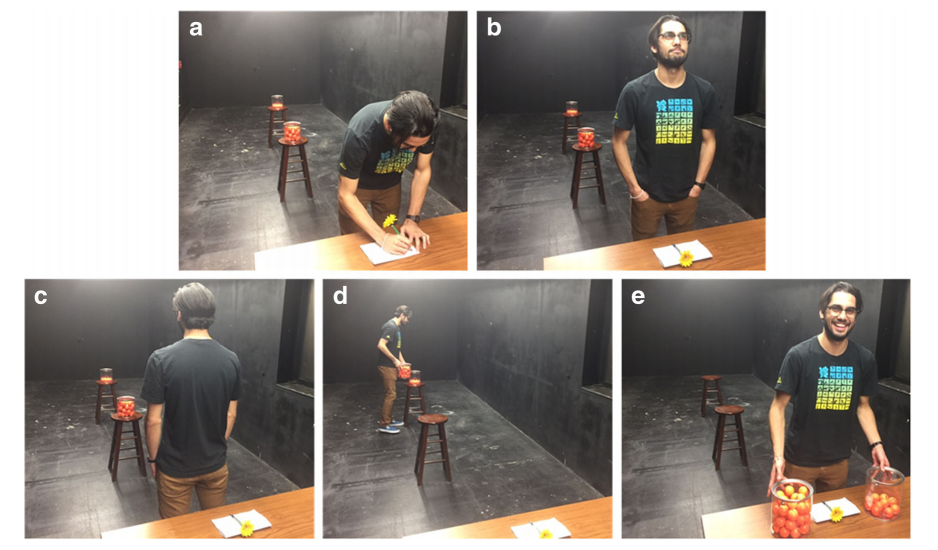

In the first experiment, (similar to the illustration above), participants were placed in front of a table and were instructed to pick up two buckets of golf balls, at varying distances, and bring them back to the table (see figure below).

Importantly, the buckets also varied in the number of golf balls they contained, such that the nearer bucket contained more golf balls than the more distant bucket. The first goal of this experiment was to assess whether participants would be sensitive to the load-bearing demands of the task and thus reduce precrastination (i.e., decrease the probability of picking the nearer (and heavier) bucket first).

The second goal of this experiment was to test for an interaction between the near-bucket preference and increased cognitive load. To assess this, half of the participants were given a list of digits to memorize and recall after returning the buckets to the table and the other half of the participants did not receive the digit list. If precrastination occurs to reduce working memory load, participants instructed to memorize the list of digits should be more likely to choose the nearer bucket first than participants without the digit list. In this case, participants could off-load tracking both buckets as quickly as possible and reserve memory resources for maintaining the digits.

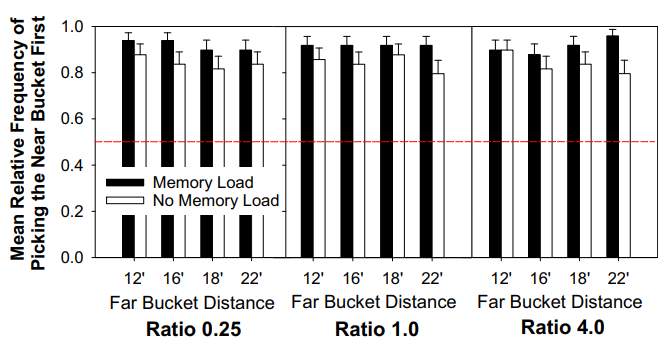

The experimenters also varied the ratio of the balls between the buckets as well as the distance of the buckets from the start line and from each other. The results of this experiment were interesting but also complex.

To highlight just a few results, the majority (but not all) of the participants in both the memory load and no-memory load groups started with the near bucket first 100% of the time, suggesting a strong precrastination preference. There also appeared to be a tendency for participants in both groups to precrastinate across all ball ratios, suggesting a potential insensitivity to the increased demands of the task. However, participants in the memory-load group had a higher probability of precrastinating when the far bucket was placed at a greater distance (see figure below). This finding suggests that increased physical effort was sacrificed when more cognitive effort was required.

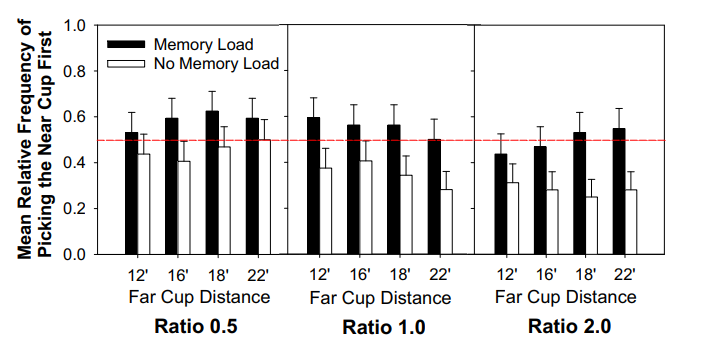

In a follow-up experiment, Fournier and colleagues further assessed the tradeoffs between physical and attentional cognitive demands. In this experiment, the buckets of golf balls were replaced by cups of water. To replicate the golf ball transport task, the nearer cup was filled with water to capacity and the further cup was only half-filled. The researchers predicted that balancing the near cup without spilling the water would increase attention demands and thus decrease picking the near cup first.

Results from this experiment, in contrast to Experiment 1, revealed that the overall preference to start with the near object first dissipated across water ratios and cup distances. However, one noteworthy, and possibly counterintuitive finding from this experiment is that the probability of precrastination (choosing the near cup first) in the memory-load group increased as attentional cognitive effort increased (i.e., distance to the far cup) (see the last panel in the figure below). This might be because when sharing attentional and cognitive demands (balancing the cup and maintaining digits in memory), the attentional demands tied to physical effort (not spilling the water) was sacrificed for the cognitive effort of remembering the digits.

Taken together, the results from both experiments suggests a tradeoff between cognitive demands and physical effort. When cognitive demands are low, a willingness to exert extra physical effort is observed. As cognitive demands increase (water transport task), the willingness to exert additional physical effort generally attenuates (i.e., reduced precrastination). In this way, overall physical behavior is structured to minimize cognitive effort.

Featured Psychonomic Society article:

Fournier, L., Coder, E., Kogan, C., Raghunath, N., Taddese, E., & Rosenbaum, D. (2019). Which task will we choose first? Precrastination and cognitive load in task ordering. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 81, 489–503. DOI 10.3758/s13414-018-1633-5.