It is truly remarkable what the mind can achieve through the process of reading. Take for example the message below.

Were you able to interpret what this message says?

Our ability to ‘read’ this combination of numbers and letters highlights the fact that reading (among other things) has become a deeply embedded feature of our cognition. We cannot help but to read anything that resembles a sequence of words. The automaticity of reading has served as the inspiration for several cognitive phenomena including the classic Color-Word Stroop effect (discussed several times on this blog, for example here and here), and the Transposed-Word effect (illustrated below).

Although some phenomena that result from reading are well known, understanding exactly how words are processed and what information about the word order is encoded during reading is less clear. Word recognition and sentence meaning are not simply dictated by the order in which words are recognized (i.e., one at a time in a sentence). Instead, researchers speculate that readers a priori associate words to plausible locations in their sentence representations. In this way, word position coding is a complex cognitive process that may be influenced by bottom-up visual cues and top-down expectations.

One view holds that words are processed serially, in a one-by-one fashion. In this way, word order information accumulates as words are appended to the sentence representation in memory. An alternative view is that words are processed in parallel, such that information about words are integrated together during processing. Parallel processing might explain why we read the above sentence “Do love you me?” as “Do you love me?” In this case, the transposed-word effect is thought to conflict with the serial-processing view. To this end, the transposed-word effect provides ample opportunity to engage the serial vs. parallel processing debate and evaluate if and how word order information is retrieved.

In a recent article in the Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, researchers Joshua Snell and Jonathan Grainger sought to  understand the role of word location in the recognition reading process. Specifically, they investigated whether word location information is processed when reading sentences or if words are processed divorced from their locations in a sentence.

understand the role of word location in the recognition reading process. Specifically, they investigated whether word location information is processed when reading sentences or if words are processed divorced from their locations in a sentence.

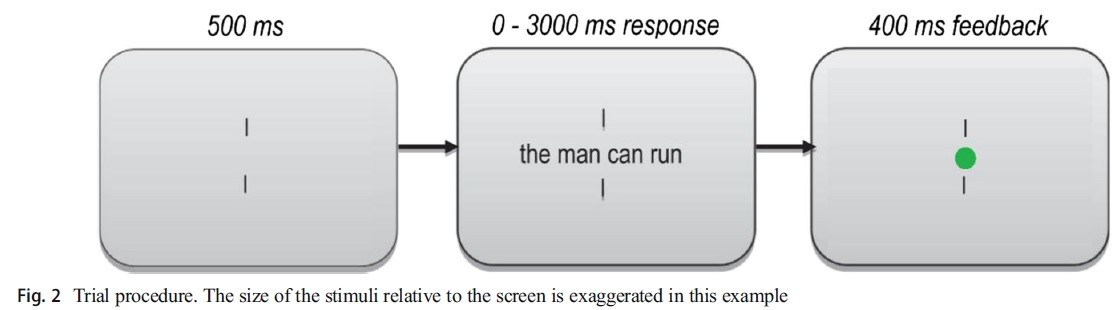

To evaluate this question, the researchers administered a speeded grammar task, where participants judged whether sentences were grammatically correct. The critical manipulation between sentences was the presented order of the words. The sentences were either grammatically intact (e.g., the man can run), the two inner words were re-ordered (e.g., the can man run), or the two outer words were reordered (e.g., run man can the).

120 four-word sentences were shown four times each: once in the inner reordered condition, once in the outer reordered condition, and twice in the intact (i.e., grammatically correct) order condition. This was to ensure that the experiment balanced the number of grammatically correct and incorrect sentence presentations. There were 480 trials in total, and as a speeded task, participants had three seconds to respond. The figure below provides a pictorial illustration of the task.

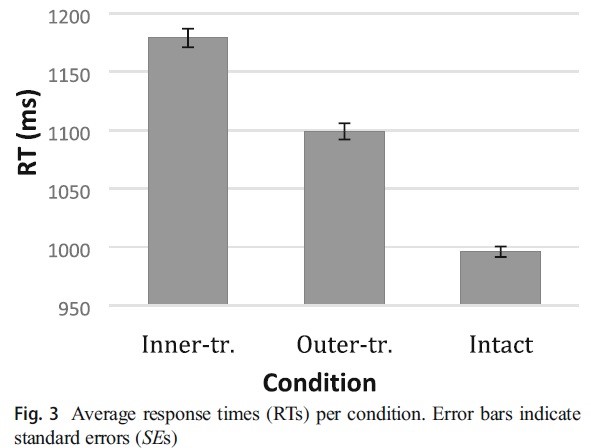

Snell and Grainger predicted that if word location is inherent in sentence processing, readers will represent plausible locations for words in their sentence representations. If this were the case, grammatical errors should be easier to detect in the outer word reordered condition compared to the the inner word reordered condition because words will appear further away from the readers’ expectation of their plausible locations. In the inner word reordered condition, words are moved one space away from their plausible locations, but in the outer word reordered condition, words are moved three spaces away from their plausible locations.

On the other hand, if words are processed independently of their expected sentence location (i.e., serially), there should be no difference in spotting grammatical errors between the inner and outer reordered sentences.

Performance in the task was evaluated by measuring response time and error. Results revealed that participants were slower at classifying inner reordered sentences (e.g., the can man run) as grammatically incorrect compared to outer reordered sentences (e.g., run man can the). These results are shown in the figure below. Similarly, participants made more errors classifying inner reordered sentences as grammatically incorrect compared to outer reordered sentences.

These results suggest that word location information is somewhat inherent in the processing of words during reading. If words were processed independently of their location in the sentence, there should have been no difference in grammaticality judgments of the inner and outer reordered sentences. This work lends further support for the parallel processing view of word recognition during reading.

So it turns out that not only is reading fundamental, but so is the parallel coding of word position.

Featured Psychonomic Society article:

Snell, J. & Grainger, J. (2019). Word position coding in reading is noisy. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. DOI: 10.3758/s13423-019-01574-0.