What are little boys made of

Snips & snails & puppy dogs tails

And such are little boys made of.What are little girls made of

Sugar & spice & all things nice

This very popular rhyme, probably written by English author Robert Southey, has persisted in western culture for nearly two centuries. It embodies western culture’s belief, or expectation, that girls are, or should be, sweet. But as we will see, this expectation is very culturally specific.

There is evidence that coordination in collaborative tasks increases prosocial behaviors between the people who took part in the tasks. And there is much less is known about when in our lifespans this starts.

There is some mixed evidence that the prosocial behaviour extends beyond the people who took part together in a task.

There is also evidence that women are more prosocial than men (but see this review). However, in Chinese culture, it is boys that are encouraged to be more prosocial than girls.

Researchers Yingjia Wan, Hong Fu, and Michael Tanenhaus explored this cultural context and tested whether a coordination task would lead to more prosocial behaviour than a shared-goal-only task in arguably the cutest group of participants: 4-year old children. Wan and colleagues present their results in a paper published in the Psychonomic Society’s journal Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

In 4-year-old Chinese children, Wan and colleagues tested the following:

- Whether coordination, over a shared-goal-only task, would lead to more prosocial behaviours;

- The extent to which, if at all, prosocial behaviours would extend beyond pairs who completed the coordination tasks together; and

- Whether boys would be more generous than girls.

There were three phases in the experiment:

Phase 1: Block Assembly Phase

In this phase children were paired and tasked with building a tower made of blocks that matched a model tower. The model tower, as shown in the figure below, had alternating rows of orange and green color blocks.

The children were randomly assigned to the coordination or the shared-goal-only condition. In the coordination condition, pairs had to work together to build the tower. One child of the pair only had orange blocks and the other child only had green blocks. In the shared-goal-only condition the children had orange and green color blocks and worked separately to build the right or left side of the tower that would later be joined to match the model. This manipulation phase allowed for comparing prosocial behavior differences between working together and working separately.

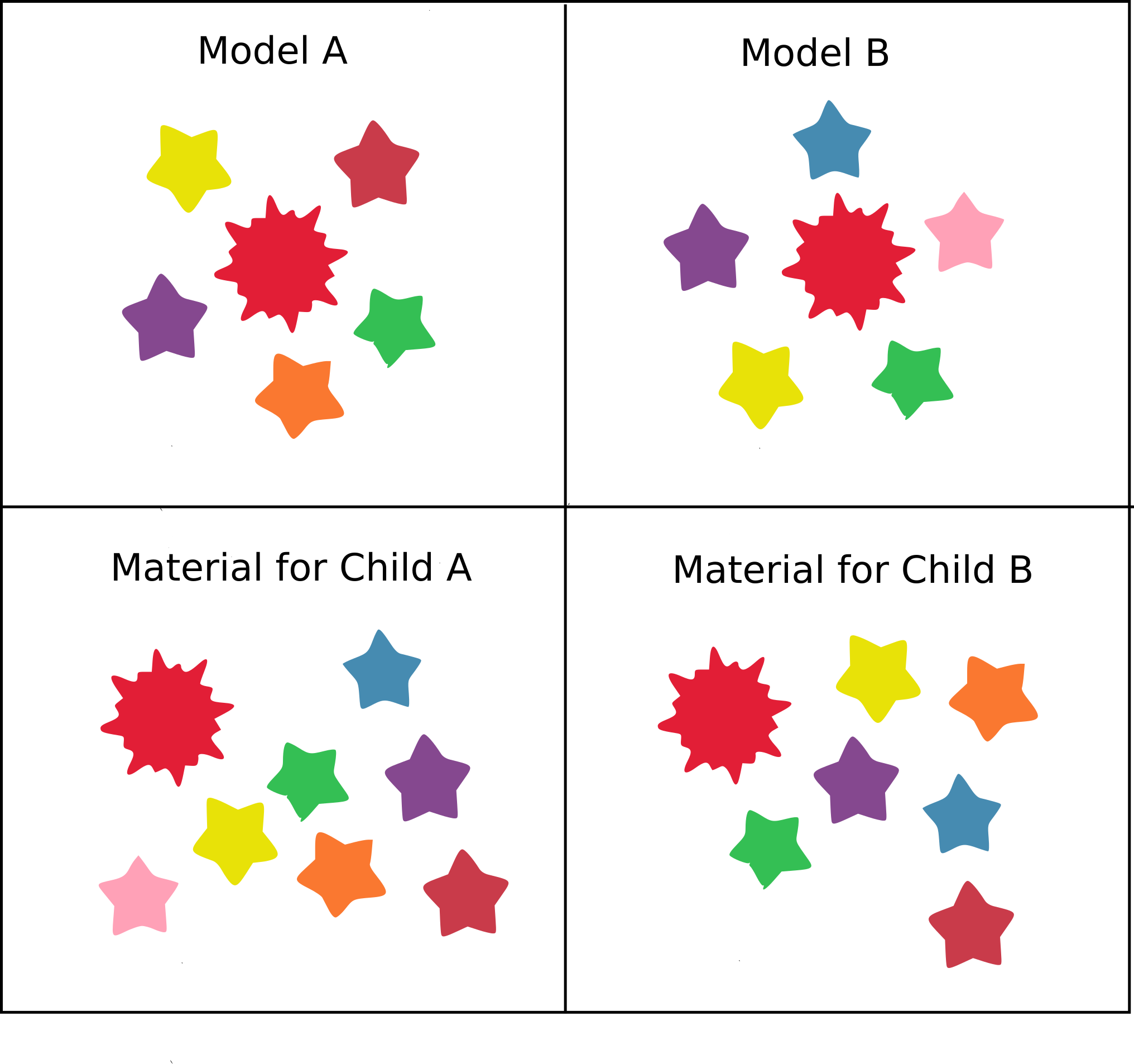

Phase 2: Star Arrangement Phase

In this phase, each child matched a slightly different model of design of stickers. As shown in the figure below, one child of the pair had one too many stickers (material for Child A in the figure) and one had one too few stickers (material for Child B in the figure) to match the model. The children were told that they could do anything they wanted if there were extra stickers. For both children to successfully complete this task, the child with the extra sticker needed to give it to the other child. This test phase allowed for measurement of prosocial behaviour within the pair.

Phase 3: Envelope Phase

In this task, each child could choose 10 stickers out of 20 stickers. The researcher said that she was short on time and could not divvy all of the stickers out to children. She told each child that they could keep their stickers or give some to other children (children who were unknown). The researcher gave each child two envelopes – one for their stickers and the other for any stickers that they wanted to share. This test phase allowed for measurement of prosocial behaviour beyond the pair.

Were the children in the coordination condition more prosocial to their partner than the children in the shared-goal-only condition in the star arrangement task? Yes. Children in the coordination condition shared in 77% of the trials with their partners so that they could complete their task. This was much more than in the shared-goal-only condition, in which children only shared in 39% of the trials. Thus, the hypothesis that coordination would lead to more prosocial behaviors was supported.

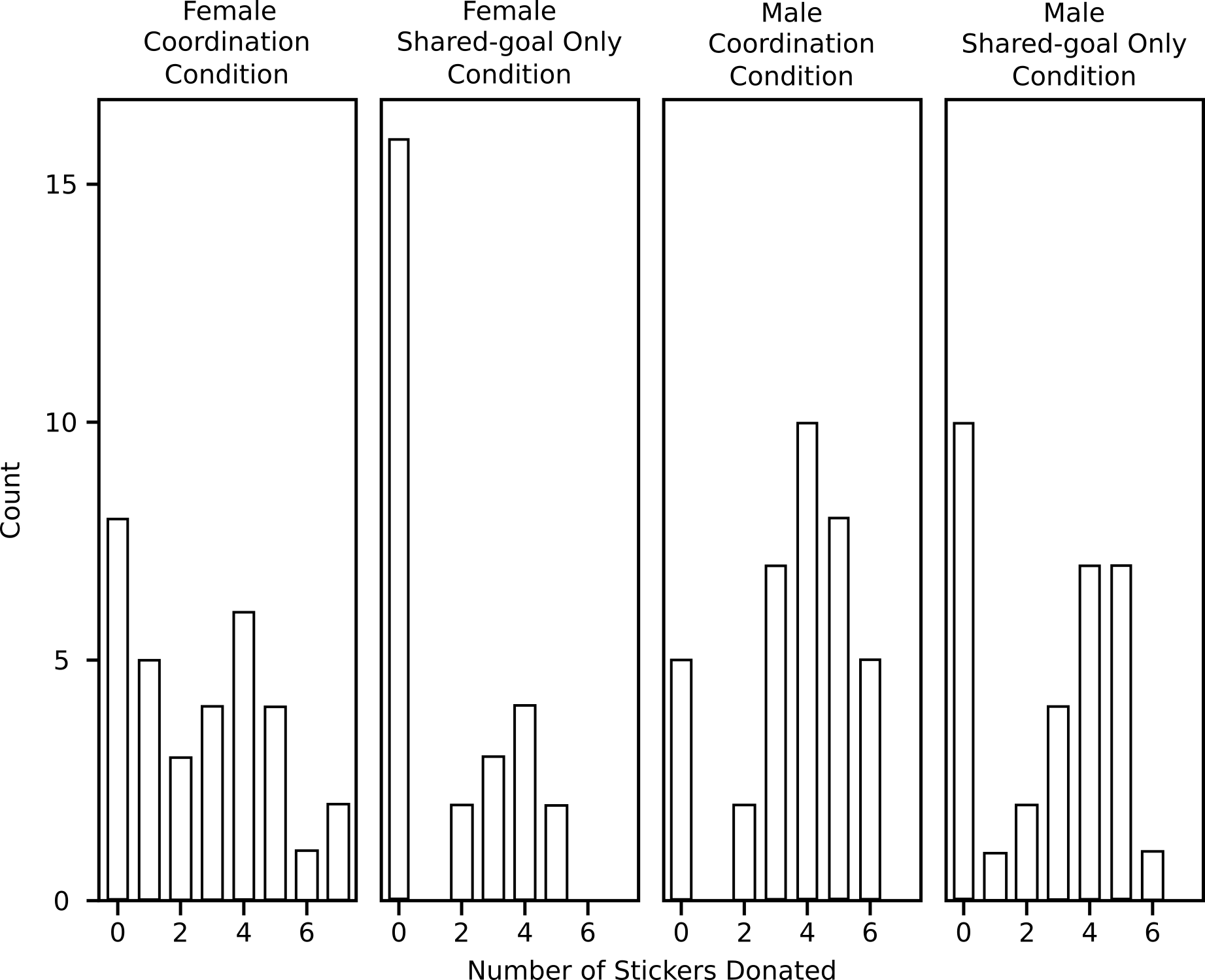

Were the children in the coordination condition more prosocial to strangers than the children in the shared-goal-only condition in the envelope task? And were boys over girls more likely to be prosocial to strangers?

Yes, and yes.

Coordination and gender impacted the likelihood of sharing stickers in the envelope task. In the figure below are the number of shared stickers by condition and gender. Children in the coordination condition shared about 1 more sticker than those in the shared-goal-only condition (3.17 vs. 2.12, respectively). Boys shared about 1 more sticker than girls (3.20 vs. 2.10, respectively).

Interestingly, coordination increased prosocial behaviour in children as young as 4 years old, and in Chinese children, boys were more likely to share than girls. The fact that in this condition, children were more likely to share than children in the shared-goal-only condition, suggests that having to coordinate increases prosocial behaviour beyong having shared goals alone.

Wan and colleagues suggested that the joint attention needed in the coordination condition may play a role, although they also questioned whether “joint attention would generalize to generosity to unknown anonymous children.”

Regarding the finding that boys shared more than girls in both tasks, the authors wrote, “Cultural effects on gender differences in prosocial development might be more pervasive than previously appreciated, a topic that clearly merits further research.”

Though not a main part of the research question, because boys are more aggressive than girls across cultures and throughout development, Wan and colleagues conducted a post-hoc, exploratory analysis of aggression. Taking or attempting to take the stickers off the partner during the star arrangement task were coded as aggressive. Lo and behold, boys were over twice as likely to behave aggressively than girls, regardless of condition.

These results call for editing the “What are little boys made of” nursery rhyme to suit Chinese children. The boys can keep their snips and snails and puppy dog tails, but maybe add some sugar and spice.

Psychonomics article focused on in this post:

Wan, Y., Fu, H., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2018). Effects of coordination and gender on prosocial behavior in 4-year-old Chinese children. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26, 685-692. DOI: 10.3758/s13423-018-1549-z.