In the late 1970s, a chimpanzee named Sarah watched a human named Keith struggle to complete simple tasks. When given various solutions, Sarah picked the solutions that would help Keith succeed in his tasks. In one task Keith attempted to grab for an unreachable object (see the left figure below). Sarah chose the option to move a crate over to stand on it to reach and grab the object (see the right figure below).

The results of this experiment were published by Premack and Woodruff in 1978. In that paper, the authors coined the term “theory of mind.” Theory of mind is the ability to understand people’s mental states. Sarah, the chimpanzee, had a theory of mind because she knew that Keith wanted to get the unreachable object, and knew how to solve his problem so that he could reach it.

The Premack and Woodruff article inspired thousands of experiments. Experiments with humans included investigations of the development of theory of mind and how it changes as we age; or how theory of mind deficits may be present in people with autism, schizophrenia, addiction, mood disorders, and so on. These experiments have resulted in a better understanding of theory of mind—however, there remains a problem. That problem is that there was no formal way to conceptualize individual differences.

To address this issue, Jane Conway, Caroline Catmur, and Geoffrey Bird developed a new theory that allows for testable predictions to better understand these individual differences. Conway and colleagues published their new theory, called “mind-space” in the Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. The mind-space framework was inspired by the face-space framework. In a nutshell, the face-space framework provides a way to understand how faces are psychologically represented. Similarly, by extension, the mind-space framework can tackle the question of how minds are psychologically represented.

published their new theory, called “mind-space” in the Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. The mind-space framework was inspired by the face-space framework. In a nutshell, the face-space framework provides a way to understand how faces are psychologically represented. Similarly, by extension, the mind-space framework can tackle the question of how minds are psychologically represented.

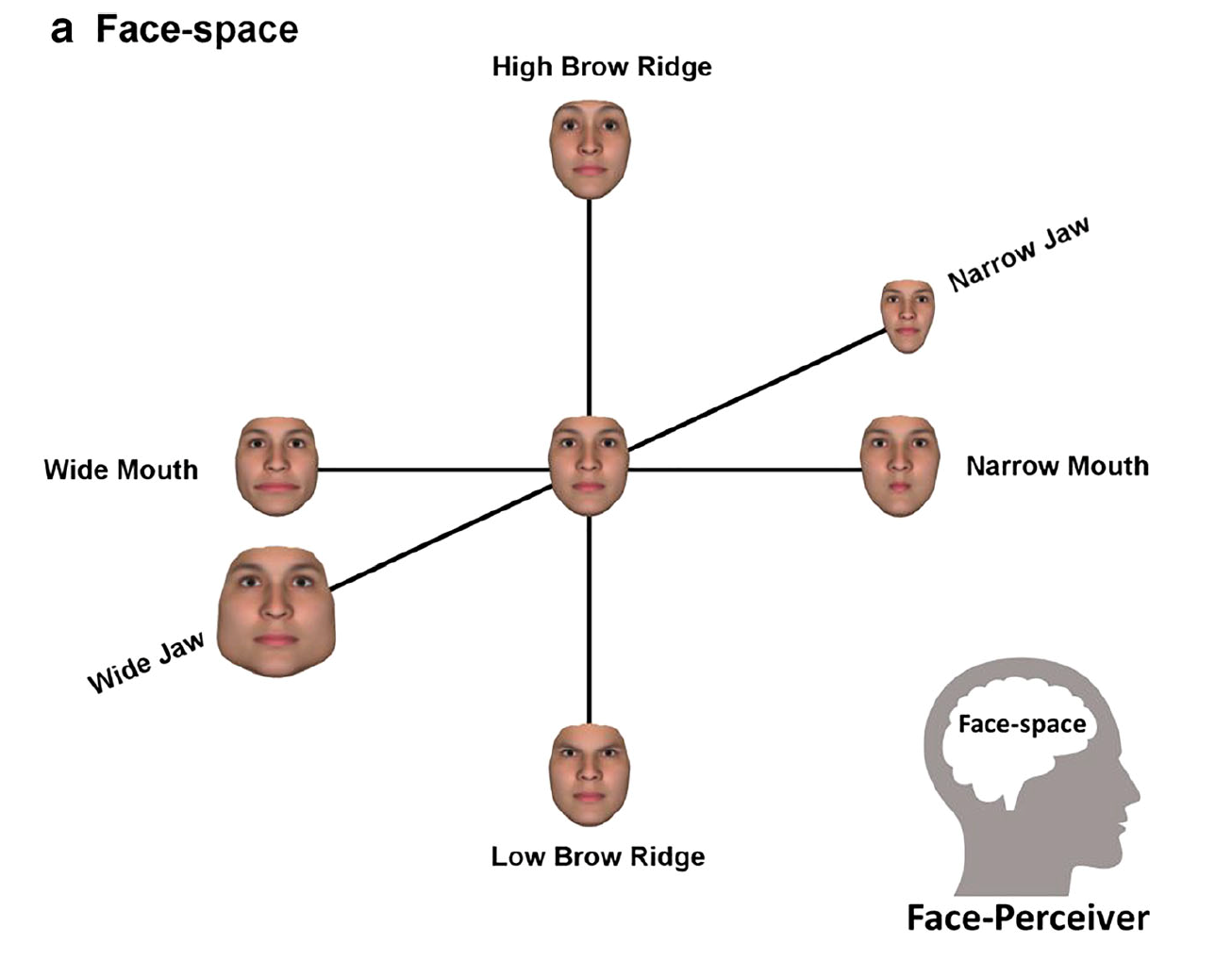

The face-space framework essentially works like this: faces are represented as vectors in the space on many dimensions. In the center of the space is the average face. Faces with distinct features move along the dimensions away from the center. The more distinct the feature, the further from the center that face would be. In the diagram below, three dimensions, mouth, jaw, and brow ridge, are represented, and as those features vary, the faces move away from the center. This framework has provided a way to test and better understand how faces are psychologically represented, and can account for many phenomena. For example, it can explain why we remember faces of people of the same race better than faces of people of other races (a phenomenon known as the other race bias).

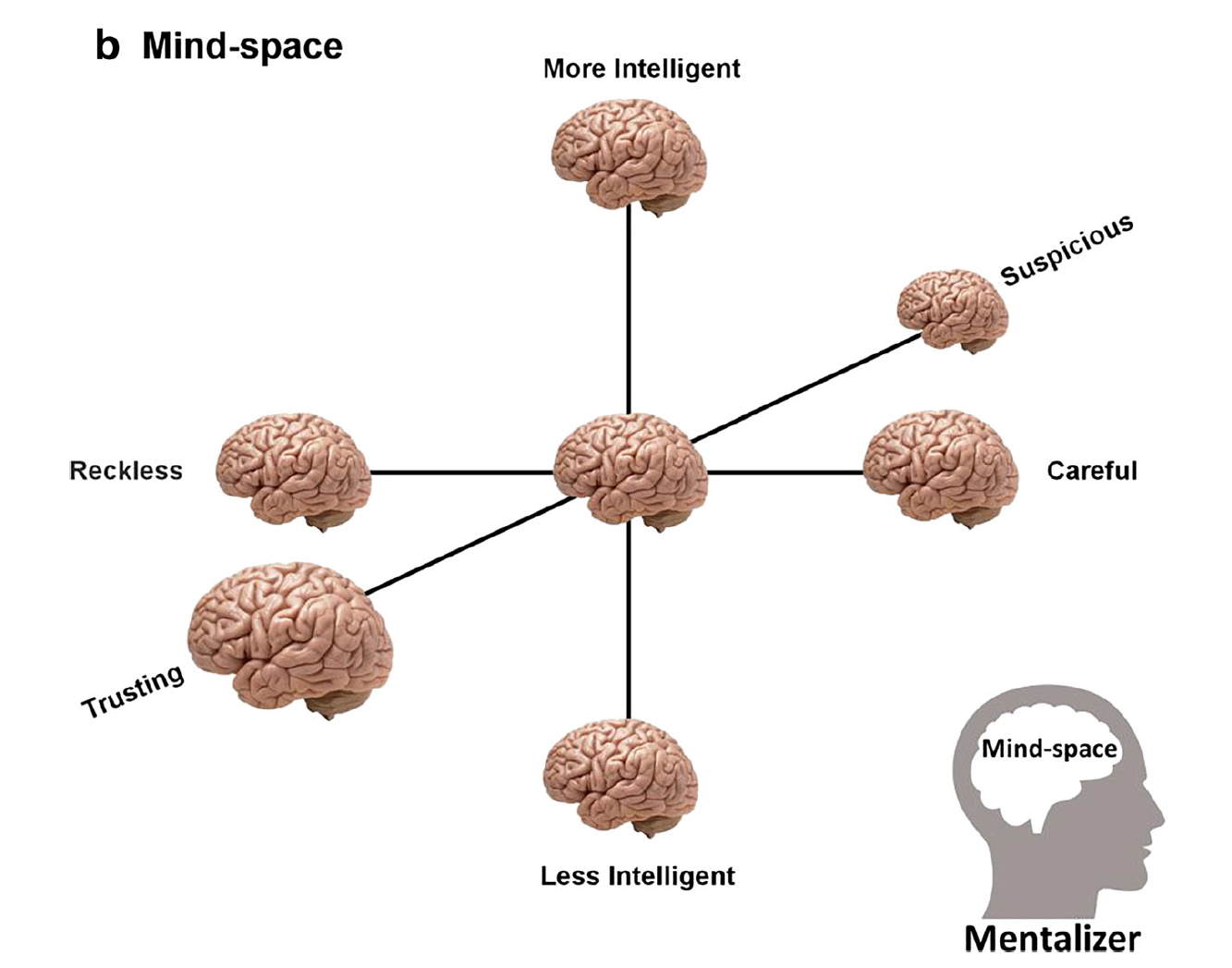

The mind-space framework created by Conway and colleagues works in a similar way: minds are represented as vectors in the space on many dimensions. In the center of the space is the “average mind”. There are many dimensions on which ways of thinking, traits, and behavioral tendencies can vary. In the diagram below, three of those dimensions, namely intelligence, recklessness, and suspiciousness, are represented, and as these things vary, the minds thus characterized move away from the center. This framework, like the face-space framework, has the potential to account for a number of theory-of-mind effects.

Conway and colleagues provide an example of a testable prediction.

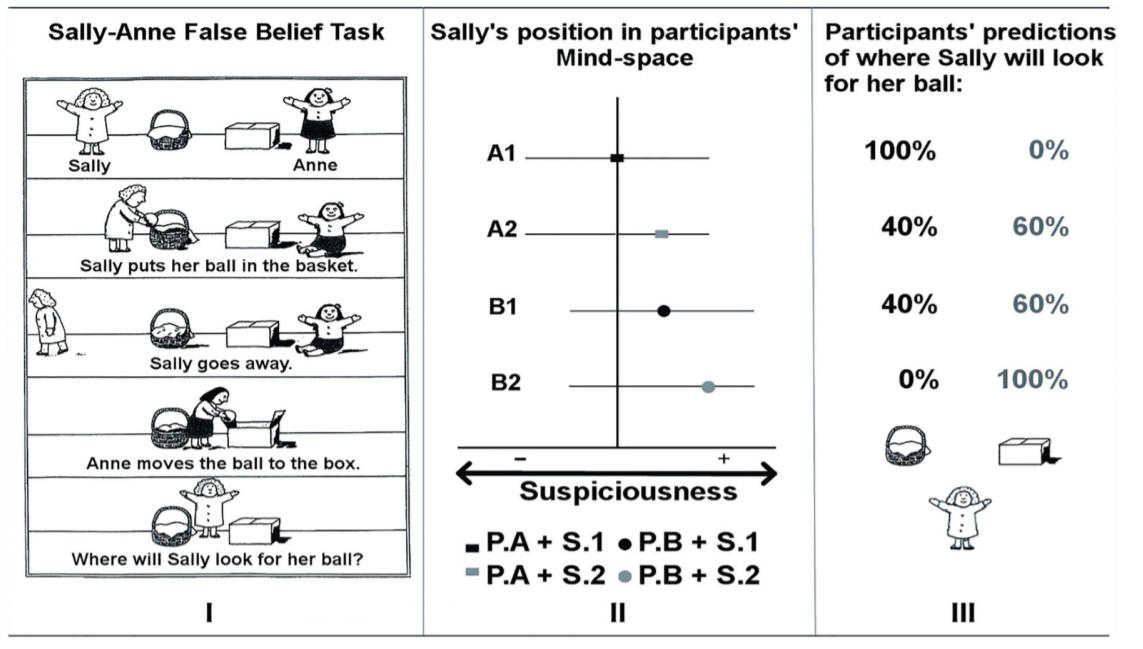

Theory of mind has often been tested using a false belief test, called the Sally-Anne task. In this task, the participant is shown two dolls, Sally and Anne. Sally has a basket and Anne has a box. Sally puts a ball into her basket, and leaves the room. When she is away, Anne moves the ball from the basket to the box. Upon Sally’s return, the participant is asked where Sally will look for her ball. The incorrect answer is “in the box” because it indicates that the participant does not understand Sally’s perspective. Sally does not know that the ball was moved, and would look in the location where she last left it. The correct answer is “in the basket” because it indicates that the participant takes Sally’s perspective into consideration.

You can see the Sally Anne task in action in this video where two children have different (and adorable) responses.

To demonstrate the utility of the mind-space framework, the authors describe a way to manipulate a dimension in mind-space, in this instance the level of suspiciousness, and how that individual difference could account for different responses in the Sally-Anne task. In the standard task, participants would have no information about how suspicious or trusting Sally is inclined to be. In that case, they would presumably represent her mind in the center of mind-space and likely say that Sally would look for the ball in the place where she left it last, in the basket.

However, the more participants think that Sally is suspicious, the less likely they would think that she would look in her basket upon her return. As shown in the figure below, as Sally suspiciousness increases, the probability that participants will say “in the basket” decreases. This is one of many testable predictions that this new framework offers.

Conway and colleagues draw a distinction between “mind” and “mental states”, where “mind” means one’s set of cognitive systems, and “mental state” means the content that is generated by the mind. The mind-space framework provides a way to better understand how these interact and how individual differences influence these interactions.

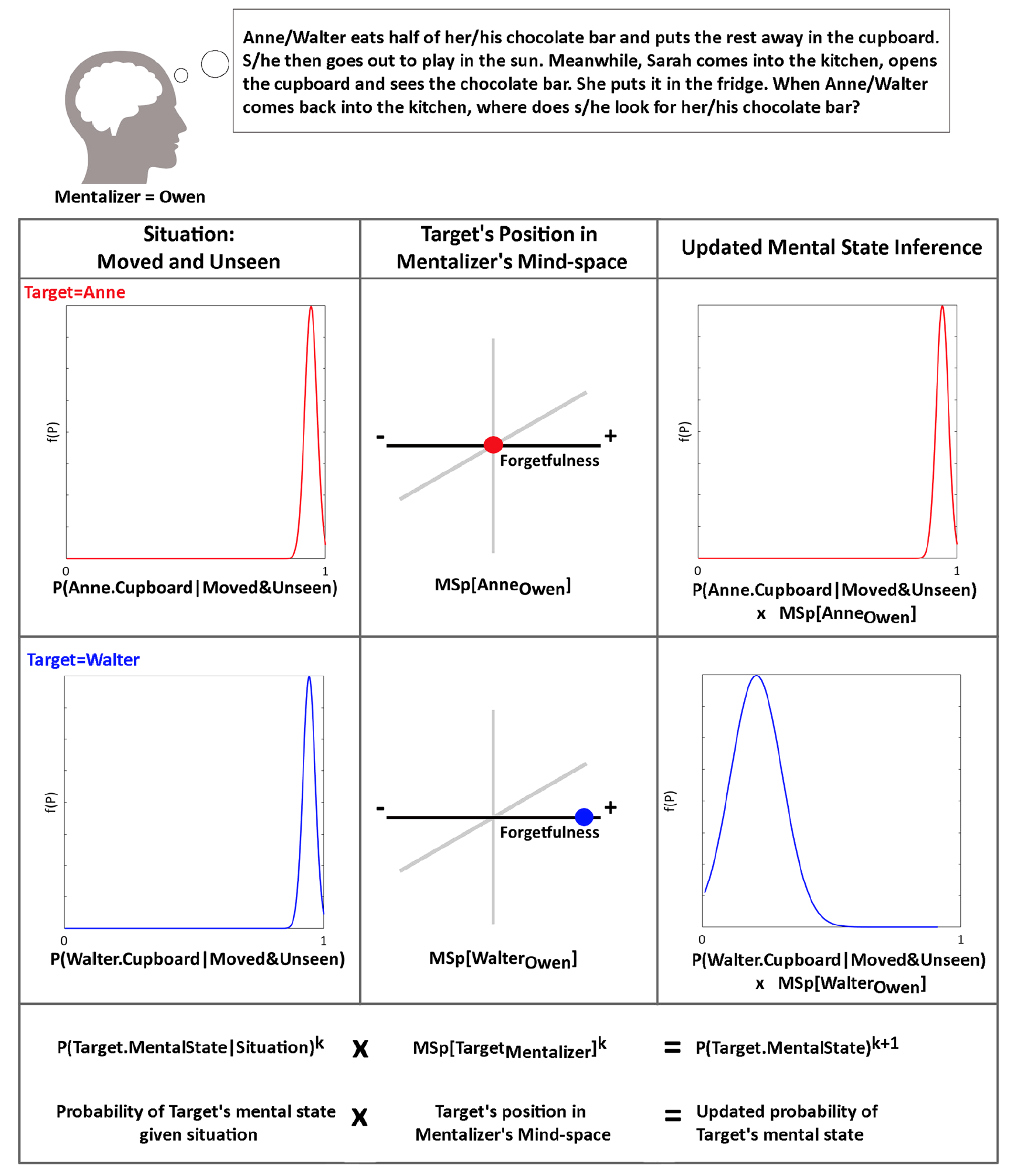

The figure below shows an illustration of how the situational factors and where the mind is located in the participant’s mind-space can differentially impact responses. In a modified Sally-Anne task, Sally and Walter both put an object away and later return to retrieve the object. The participant (referred to as the “mentalizer”), Owen, first predicts that Anne and Walter will look for the object where they last left it, but when he learns that Walter tends to be forgetful, he changes his response about where Walter will search for the object upon his return. This is another testable prediction made by this new framework.

This new mind-space framework has great potential to impact our theoretical understanding of the theory of mind.

The framework addresses the major problem in the field by providing a way to investigate individual differences by generating many testable predictions. And the mind-space model links mind representation with mental state inference. The authors wrote,

“We hope that this introductory sketch of mind-space is a first step towards an understanding of individual differences in the representation of whole cognitive systems, where minds are recognized as complex multidimensional stimuli. It should be noted, however, that even if minds are not represented in a multidimensional space, the ability and propensity to represent another’s mind is still likely to be an important source of individual differences in the accuracy of mental state inference.”

I personally look forward to tracking the impact that this framework has on the field.

Psychonomics article focused on in this post:

Conway, J. R., Catmur, C., & Bird, G. (2019). Understanding individual differences in theory of mind via representation of minds, not mental states. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 10.3758/s13423-018-1559-x.