In this episode of All Things Cognition, I interviewed Zoe Hughes (pictured below) about her meta-analysis published in the Psychonomic Society journal Psychonomic Bulletin & Review on the effects of mindfulness on creativity with co-authors, Linden Ball, Jeannie Judge, and Cassandra Richardson. We talked about different types of creativity and which was more impacted by mindfulness. We also discussed the level of mindfulness training that participants need before the strongest effects appear.

Interview

Transcription

Intro

Kosovicheva: You’re listening to All Things Cognition, a Psychonomic Society podcast. Now here is your host, Laura Mickes.

Interview

Mickes: I’m talking with Zoe Hughes about her paper. Published in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review called a “Meta analytical review of the impact of mindfulness on creativity, framing current lines of research, and defining moderator variables.” Hi Zoe, thanks so much for talking to me about your paper.

Hughes: Hi, Laura. Oh, it’s great to be here. Thank you so much for having me.

Mickes: You had some co-authors on the paper. Who were they?

Hughes: So the co-authors were Linden Ball, Jeannie Judge, and Cassandra Richardson.

Mickes: So it was a whole team effort,

Hughes: A group effort, definitely. Yeah.

Mickes: Although this is probably unnecessary because everyone knows what it is, but it maybe start with a definition of mindfulness. Could you describe it or define it?

Hughes: Sure. Yeah. I definitely think it’s got more popular now, so I would imagine lots of people do know what mindfulness is at the moment, but for those who don’t, I guess the best way to describe it is that it’s a form of meditation, which aims to bring attention to the present moment without feelings of judgment or feelings of overwhelm. And it’s probably worth saying as well that it can be practiced in lots of different ways. So a lot of people view mindfulness as kind of this sit down, eyes shut, meditative type mindfulness, whereas actually you can practice it in so many different ways. You can practice it while you’re walking and you can practice it on your mobile phone, in your headphones. You can do these full body scans just before you go to bed. And so there’s so many different ways that you can practice it. So it’s really accessible and I guess that’s what’s so good about it. And yeah, it’s accessible to, to so many different people and in lots of different ways as well and different intensities, which is nice.

Mickes: Right. You investigated the impact of mindfulness on creativity. There are different types of creativity. Did you focus on…I I think you focused on maybe a couple of them.

Hughes: Yeah. Lots of the literature currently or before the review that we were reading typically looked at creativity as kind of one whole construct. And I guess that’s where we had a problem because lots of the studies seemed to report that mindfulness sometimes was beneficial, sometimes it had no impact. Sometimes it was even detrimental to creative performance. So there was obviously something going on that made it very complex. We wanted to separate it in a way that we could separate it easily into two groups without making it too complex. But we definitely wanted to look at it from a different perspective.

Mickes: Right.

Hughes: What we decided to do was separate all of the studies that we reviewed into two categories, and those categories were convergent and divergent creativity.

So just to give a background of each of those, convergent creativity is tasks that require one singular correct solution. So we ask participants to think of one single solution. So, this could be for an example, a compound remote associates task (pictured below). And an example of this is participants are provided with three cue words and are asked to produce a fourth target word that forms three compound phrases. So a participant might be presented with the word “sense”, “courtesy” and “place”, and the solution target word would be “common.” So that would form compound phrases like “common sense”, “common courtesy”, and “commonplace”. So there’s correct answers.

Hughes: It’s different to divergent creativity in that they can just think of as many creative solutions as they can come up with. For example, we’d give them an item like a brick, and we’d ask them to think of as many common uses as they can for the brick.

Mickes: Right.

Hughes: This is where we see a huge amount of variation. So we typically score these on things like originality, usefulness. So they might think of to use a brick as a doorstop, or they might think to grind up the brick to use the dust for red ink or something like that. You can see the difference in how creative you can be with that one.

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: So as an umbrella term of how to describe these convergent problems require one singular correct solution, whereas the divergent problems, you just think of as many creative uses as you can.

Mickes: Okay.

Hughes: That’s why we decided to categorize our tasks into, just to get a bit more of an idea of what was going on really.

Mickes: Right. And a meta-analysis sounds like it was really timely if you’re getting all these results. So sometimes they don’t find a difference. Sometimes they do. And so that’s why you decided to, okay, we’re gonna do this meta-analysis and we’re gonna use these two different types of creativity

Hughes: By grouping them all into just convergent or just divergent tasks, we were able to get some clarification as to how mindfulness was impacting each of those types of creativity. Right. Although I will say there is a little bit of difficulty into categorizing them completely into their own groups. There is a slight little bit of overlap between the processes that are involved in convergent and divergent creative processes. So a little bit of overlap, but that was the best way for us to sensibly group them.

Mickes: Right.

Hughes: So it’s the best approach, I think.

Mickes: How many studies were included in the meta-analysis?

Hughes: So we had a total of 37 studies included in the whole meta-analysis, which I think shows that it’s still a growing area of research. But it was a good time for us to do it, I think because although it’s still a small area, it’s still very confusing. And there was really no general consensus as to what this relationship was. So it was a good time point for us to do it because moving forward, as it grows in popularity, which I hope it does, I think our results and our recommendations will help to guide future research and to perhaps get researchers to think a little bit more about maybe study design or the type of creativity tasks that they’re looking at.

Mickes: Right.

Hughes: Or the, the intervention and things like that. So I think it was a good time to, to pull the review together.

Mickes: Right. People go about it either by including a control group and having a mindfulness group, or they do this pre- and post-test. Did you separate it based on that or that was a separate consideration? Yeah, I think it was separate.

Hughes: Yeah, we separated it. The main reason for that is, had we have kept them all, all 37 studies together, we couldn’t have really reliably compared them. So we couldn’t have compared the studies that take measurements before and after the intervention to a study that compared the intervention group with a control group, what we decided to do was first separate them. So we actually carried out two meta analyses in the paper.

Hughes: The first looking at just the pre and post test studies and the second looking at the control group studies with the control group studies, we then further had a moderator analysis or a subgroup analysis, which looked at the different types of control groups. So not only were we able to then run separate analysis for the two different study designs, we were able to really understand whether the type of control group that was being used, for example, whether it was an active or a waiting list control group or no treatment control group, had an influence on the results as well.

Hughes: So again, we just tried to really understand what was happening and to see the influence that study design was potentially having on the results as well.

Mickes: Right. Did you mention waiting list?

Hughes: Yeah, so waiting list, just to give that, uh, yeah, a little bit of background. So a waiting list control group is often used more so for I guess, ethical reasons. What happens is the waiting list control group, they don’t do anything whilst the other group experiences the intervention. So they just kind of relax. They don’t do anything for, for that amount of time. But then after we collect that post measurement or the data collection of the post intervention time point, we then give them the intervention as well.

Mickes: Okay.

Hughes: So that means that ethically, if we are saying that mindfulness is beneficial for range of things, we then offer it to everyone and, and no one’s at a disadvantage by being placed in the intervention group as opposed to a no treatment control group.

Hughes: But then there are some limitations of using this waiting list control group as well. What we tend to see, and actually what we did report in our review as well, I won’t jump ahead to the findings, but I’ll just, while we’re mentioning it, what usually happens when people are placed into a waiting list control group is they get really excited and they, they know that this course is coming up. So they start doing a little bit of research. So say if they were about to start a mindfulness course, this might prompt them then to download a mindfulness app or to start learning about it. And so what we see is that pre and past measure where they weren’t supposed to be doing anything, they actually are doing something in there.

Mickes: Oh,

Hughes: And that leads to,

Mickes: …interesting.

Hughes: yeah. So that can lead to inflation of effect sizes.

Hughes: So that’s quite a big problem with, with all intervention studies I guess, but specifically in mindfulness as well, we do see that people are going off and doing their own thing and trialing their own methods of meditation or even, even not mindfulness. They might just try something else or they’re learning more about it, they’re being more mindful naturally.

Mickes: Wow.

Hughes: And this changes their post-test results to what we would’ve expected if they didn’t do anything at all. So it can be a little bit problematic. And we did see that in our review as well. It’s something we have pulled out towards, towards kind of the discussion area of the review. And I guess it’s something for future research to really consider when they’re thinking about study design, is that, yes, waiting list control groups are really useful when there’s ethical reasons to include them. But otherwise we kind of come to the conclusion that we would strongly recommend future research use active control groups instead.

Mickes: Right. What is an active control group?

Hughes: So an active control group as opposed to a no treatment control group is where the control group do get to do something. And so instead of a mindfulness intervention, which the uh, intervention group will experience, they may sit in a room and do yoga instead if we wanted to compare them or they do something along similar grounds, right. Just without the specific characteristics of mindfulness.

Mickes: Okay.

Hughes: So it could be identical in length, in intensity, in duration, but it just doesn’t include those specific characteristics that we are really interested in. So with that, paying attention to the present moment nonjudgmentally. So it just skips out that area that we are looking at. And what that enables us to do is if there are any group differences, we can then confidently say, well, the only difference in what they did was those mindfulness characteristics. So it must because of those that we’ve seen these outcomes.

Hughes: So active control groups are preferred. You do get a lot of studies still using these no treatment control groups as well. And I guess you can kind of understand what that is from the name in that the, the control group doesn’t do anything again.

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: – quite similar to that waiting list control group, but they don’t get to do the intervention at all. They just don’t do anything during that time. So yeah, that’s kind of the difference in, in the control groups. And, and we did separate the studies based on the control group they used and we ran some moderator analysis on those.

Mickes: Okay.

Mickes: Well I guess we should get to the bottom line. What’d you find?

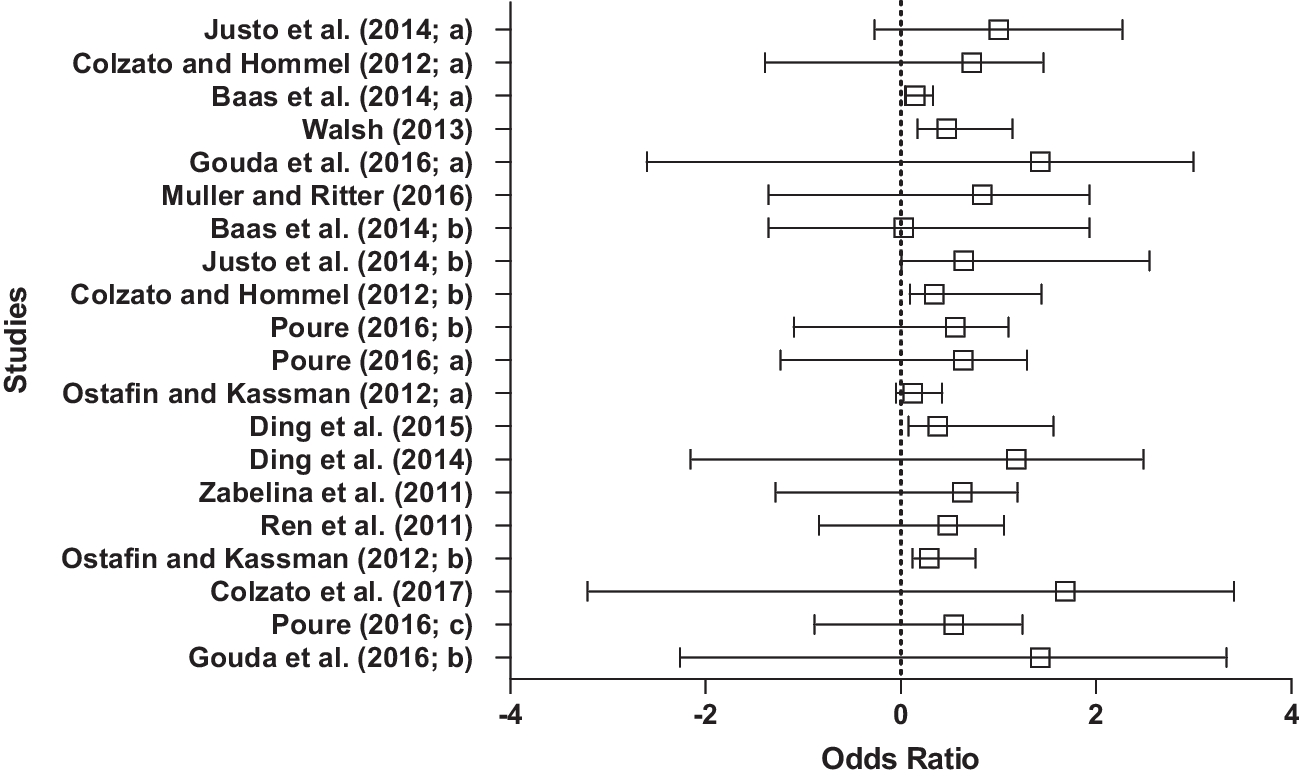

Hughes: Yeah, I’ll try to describe it in as logical way as I can. So I’ll describe it in the same order that we did in the paper. And I’ll start by just telling you overall what we found for the main meta-analysis. And then I’ll go a little bit in depth of the subgroup analysis as well, so we know the moderator variables. So firstly, we did find that mindfulness was beneficial for creativity in both groups.

Mickes: Oh.

Hughes: So yeah. So that’s pretty cool findings.

Mickes: That’s cool.

Hughes: For the control group studies, we had an effect size of 0.42. So this told us that for studies using these control group designs, mindfulness interventions were successful at improving creativity with this small to medium effect size. So that’s great. For the pre and post designs as well. We found another significant effect of mindfulness on creativity, which told us that mindfulness increased creativity with a medium effect size of 0.59,

Mickes: hmmm!

Hughes: Higher effect sizes for those pre and post design studies. And we do offer some explanation as to why we do in the review, and I can touch on that a little bit later.

Mickes: Okay.

Hughes: Otherwise I’ll, I’ll end up going on lots of tangents when I talk about all the results.

Mickes: Okay.

Hughes: So they were the kind of the main effect sizes from our pooled meta-analyses. So when we looked at the moderator variables, so our second aim of the paper was to understand what the most influential moderator variables were in this relationship between mindfulness and creativity. So the things we looked at were the type of creativity that’s being measured. As I mentioned, we categorized into convergent and divergent creativity. We also looked at intervention length as well, because this varies so much in the literature. Some studies look at what we call inductions, which is kind of just five or 10 minutes here and there, while other studies look at really long-term structured mindfulness courses and.

Mickes: mm-hmm.

Hughes: An example of that is the mindfulness-based stress reduction course. So that’s an eight week structured, quite intense course. It’s, it’s weekly meetings with daily home practice. So you are on that when you’re on that course. It’s, it’s every day.

Mickes: Wow.

Hughes: And so it can be quite intense. And currently in the literature, researchers tend to think that the longer the mindfulness course, the more intense the mindfulness courses, the stronger the outcomes, which I guess makes sense people are getting more chance to practice it. And

Mickes: Did you find that?

Hughes: I guess, yeah, we did. So for the studies that utilized a control group, we did find a significant difference between the intervention length that was employed and the outcomes on creativity. And to say more about that, medium interventions were actually the most effective with medium effect size of 0.55. And that was followed by the short interventions with small to medium effect size and then long interventions with a small effect size.

Mickes: Whoa.

Hughes: So this is quite surprising.

Mickes: That is surprising if people expected it’s the long ones that …

Hughes: Yeah. So, yeah, we would expect that longer interventions would increase the effect size. We’d see more stronger outcomes on creativity. But we found that yeah, the strongest effect came from these medium length interventions and, and these were anything from 20 minutes to one week. So it’s quite a broad category.

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: It was a difficult one to explain why we saw that actually. We’re not really entirely sure.

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: But I guess it comes down to our grouping. So we grouped things on short being anything under 20 minutes, medium between 20 minutes and one week, and long, anything over that one week mark. And perhaps that had something to do with our grouping. There’s no real set guidelines as to how you categorize mindfulness interventions into short, medium, or long. And I’m sure every researcher would approach that a little bit differently. So it could have been that we grouped them potentially a little bit differently than we should have. But yeah, we found the most strongest effect sizes in this medium category, which I don’t really know why we did, but I think it’s great that we did because it just means that anyone who was thinking about using mindfulness as a tool to enhance creativity, they wouldn’t have to sit for eight or 12 weeks and do daily practice.

Mickes: Exactly. That is good news.

Hughes: Yeah.

Mickes: For researchers who are continuing to do this, all right, well I don’t need an eight-week course for my participants. That’s really helpful to know.

Hughes: Exactly. Yeah, that was one of the points that we made towards the end is that perhaps researchers shouldn’t feel the pressure to, to have to put on these structured long-term mindfulness courses where they bring in a mindfulness instructor. Perhaps we see the same effects from just half an hour in the lab or a few days or anything under one week, which is gonna be really helpful when it comes to participant recruitment. It’s gonna be really helpful when it comes to funding and things like that.

Mickes: Yes, exactly.

Hughes: Yeah. It’s a great thing, I think.

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: like I said, I’m not sure why <laugh>, but yeah, I’m not gonna argue with it. It’s, it’s probably a good result.

Mickes: Someone else can then look at the data and group it differently and…

Hughes: yeah. Perhaps, yeah.

Moving forward, perhaps that’s something we could look at as to if we did group things differently, if we did look at the literature in a different perspective, would we see different results. But the aim of grouping it was to really just ensure that those long-term interventions or anything structured that was delivered by a professional mindfulness instructor was grouped together. And all these inductions, which is typically anything 20 minutes or under were grouped together as well. So that was really our only way of doing that was to then have this quite broad category of 20 minutes to one week. Perhaps there’s something more there where we can look at just these 20 minutes to one week and further examine those as to whether it’s, you know, longer than one day or shorter than one day.

Mickes: Right.

Hughes: So that might be something that, that we look at in the future.

Mickes: Oh, that sounds like a good future direction.

Hughes: Yeah.

Mickes: You know, I published a paper on mindfulness once participants did a mindfulness induction. I think we had a regular control group or a passive maybe, I can’t remember the details, to tell you the truth, but they all took part in a recognition memory test and the people who did the mindfulness training had more false alarms than those who didn’t do the mindfulness training. Yeah. So a lot of people didn’t like that finding and said our induction was too short. And now I can say, well, look at this meta-analysis <laugh>.

Hughes: Yeah, we’ve kind of carried on this research and done some more empirical work looking at these shorter term mindfulness interventions. And I, I won’t go off on a tangent and discuss that, but I will just say that we found the same thing. We, we found really promising outcomes from just 10 minutes of SAT doing a breathing exercise and that was on just cognition, attention and things like that. So.

Mickes: Right.

Hughes: Yeah. We shouldn’t completely dismiss these really short,

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: Short interventions or inductions and actually they might be really valuable and certainly a lot more appealing to most people I think.

Mickes: Yeah, exactly. Eight weeks doesn’t sound that fun to me. So, okay, so what, what were the other findings?

Hughes: The control group, we saw that these medium interventions were most effective. Our findings were a little bit different for studies using the pre and post design though. So we had no significant difference between intervention length in these designs. So if researchers were looking at before and after intervention, it didn’t matter the length of the intervention at all. We still saw an effect to creativity.

Mickes: Wow.

Hughes: Which was really interesting. So that again, just speaks towards the importance of ensuring you have an appropriate study design.

Mickes: Yes.

Hughes: Again, yeah, it’s always important and we were able to make some recommendations for future research in our paper as well because of that.

Mickes: Mm.

Hughes: So I guess moving towards the really fun findings that we found. So when we look at the type of creativity that’s influenced by mindfulness, we found that convergent creativity was, well, benefited more than divergent creativity from the mindfulness practice.

Mickes: Oh, so coming to one answer that,

Hughes: Yeah,

Mickes: kind of creativity.

Hughes: Yeah. So when there’s one singular correct solution, people were better at doing that after mindfulness than just producing lots of creative ideas. Not, well they both were benefited from mindfulness, but that it was that convergent creativity that seemed to benefit a little bit more and we found that really difficult to explain why – it’s not something we expected to see.

Mickes: That was what I was gonna ask you, why?

Hughes: We have some, we have some explanations as to why, and I’ll just speak towards them. But I think most of these are very much just proposed explanations and there is more work that needs to be done. So in terms of why mindfulness might be improving creativity first for each of them. And then I’ll touch on why convergent more than divergent. So mindfulness enhances divergent thinking in tasks such as the alternative uses task. We think by increasing the efficiency of brain networks such as the executive control network, the default mode network, thereby enhancing executive aspects of attentional processing that are required to do well on these divergent thinking tasks. So that’s very much kind of what is already proposed in literature. It’s very in line with what we call the business as usual view of creativity and that it’s a very analytical step-by-step process to reach your solutions. So that makes sense to us and, and I think that’s a reasonable conclusion to come to. Whereas when we look at the convergent creativity, we kind of have this alternative explanation of our findings that’s perhaps more new to the field. So that is that the act of practicing mindfulness might instead of improving just one aspect of attention or one aspect of cognitive control, it improves the ability to flexibly shift between different modes of attention.

Mickes: Oh.

Hughes: Which allows for participants to go from this de-focused attention or this broad attention right back into this focused attention again and keep shifting between the two. And the reason we think this is the case is because when we’re solving solving these more convergent type problems, we have to inhibit an incorrect solution. So once we’ve evaluated a solution, we’ve realized that it’s an incorrect one, we then inhibit it and we come back towards this evaluative stage or this idea generation stage where we again have this broad or diffused attention, we have to think of as many ideas as we can, and then we focus in again and we evaluate this specific idea. If it’s correct, great. If it’s not correct, again we inhibit it and we go back to this broad attention. So it is this need to shift between two different types of attention. And actually that’s exactly what you do in mindfulness.

Mickes: Oh.

Hughes: So some of the common areas of mindfulness is that first you focus on this focused attention, which is what you focus on the breath or you focus on a specific part of your body or a sensation, but it also has this open monitoring attention as well where you are very aware of your surroundings in a non-judgmental type way. So it, over time when you’re practicing mindfulness, it does encourage this ability to shift between two different types of attention. Exactly what’s needed for this convergent creativity.

Mickes: Right.

Hughes: So that’s our explanation as to what’s going on then. And as far as I’m aware, I don’t think many people have really proposed that as an explanation yet.

Mickes: It’s a testable idea and it’s not the same old idea that everyone talks about. It sounds exciting.

Hughes: It is exciting. I think that’s where we’re at currently. So in terms of what we’re doing now, this is what we’re trying to test. We’re, we’re kind of playing with the idea of writing a position piece on this, is mindfulness actually encouraging this cognitive control to improve flexibility? So if we start there, if we can see first, if mindfulness is doing that, then we can bring that over to creativity if we see that it is. But I think it’s exciting and it’s something new to the field, something that’s not been considered before that. We’ll definitely, yeah. We are testing at the moment. Um, yeah. And hopefully, well, who knows, maybe, maybe we’ll see something with that. Maybe we won’t, but it’s exciting that we’ve been able to pull that out of a, of a review piece and offer something new. I think it’s, it’s nice.

Mickes: Yeah. Excellent.

Mickes: Did your reviewers give you a hard time about any of this, the new idea, the way you grouped things? Did the reviewers have any problem, or did it sail right on through?

Hughes: <laugh> No, it didn’t sail on through. We did get lovely reviewers, um, but they were great. They actually made us think about things that we hadn’t thought about. And they did pick up on things like, why did you group the interventions as small, medium, and long? Like that was a strange way to do it, but we really didn’t know how else to do it. You know, we had to start somewhere. And although the reviewers raised this as a point, it wasn’t really a critical point, it was just could you provide a little bit more explanation? And really our explanation for that was just that, well we, we didn’t really know another way to do it. We wanted to make sure the long-term interventions, so the structured ones were together and the induction ones were together. So, um, they were fine with that. Yeah, so great. They give us a hard time with that. They did question again, the grouping of convergent and divergent.

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: And they offered some recommendations that perhaps this could have been split in terms of type one and type two processing, but when we reviewed it, we found that there was much more overlap when it came to type one and type two processing than there was with convergent and divergence.

Mickes: So, so convergent-divergent is the better grouping then.

Hughes: Yeah, that’s what we concluded anyway. And the reviewers seemed, seemed happy with that. I think it sets the scene for us now a little bit better in terms of – there is a relationship between mindfulness and creativity. It does seem to be doing something perhaps with this flexibility but perhaps with different mode networks or something’s going on there. And our review confirms that and now we need to put in the work to understand exactly what is going on, just to further understand that relationship. I guess that’s what me and my co-authors are, are up to at the moment as well and trying to just continue on with it.

Mickes: Okay. So you’re following up on, on doing studies, individual studies now?

Hughes: Yes, we are. So we’ve currently got some intervention studies going on. We’ve also opted to do some studies looking at just trait mindfulness, so getting rid of the intervention, just seeing if there’s a correlation between trait mindfulness, dispositional mindfulness and creative problem solving. And if there is, then we don’t need to always have the intervention inducing the outcomes. Would we see the same outcomes from someone who’s just got naturally occurring mindfulness traits? And…

Mickes: Right.

Hughes: the reason behind that again, is we know that by practicing mindfulness over and over it can create changes to trait mindfulness. So we’ve kind of made it easy for ourselves in a, in a sense and skipped that stage of having the intervention all the time and gone straight onto just mindfulness traits and if we can see effects that way, and if we can then, we can go back and investigate that in more detail with an intervention. But it just makes things a little bit easier not having to have these long-term intervention based studies all the time, I guess.

Mickes: You’re doing some good follow ups on this meta-analysis and I saw that you had several recommendations for researchers doing mindfulness studies. Do you wanna name a few?

Hughes: I think it’s an important part of the review paper. And the, I guess, the main reason we’ve done this is to help future research carry on with this, the research that’s looking at mindfulness and creativity. So yeah, I can definitely include some of the main ones that we’ve addressed in our paper. So the first is the use of active control groups. So our findings do support the use of these active control groups, but we do still highlight that there are limitations in these active control groups being too varied or too broad. And what we do suggest is that moving forward a clear definition of active control groups is required to just ensure consistency across studies.

Mickes: Right.

Hughes: And so we’d recommend that that’s something that researchers work on in ensuring we’ve got these appropriate active control groups across all studies.

Mickes: Yes, that’s a sound recommendation. Really good.

Hughes: I think so, it’s definitely we’re trying something we’re trying to do include in our own work moving forward as well to making sure we’re being consistent with them and we’re using yeah, relevant and appropriate active control groups. In terms of study design as well, we also think that our review further highlights that this is something that should be carefully considered in future studies. So the current analysis that we conducted supports the use of these pre and post measures, but that should not completely kind of discredit previous criticisms, um, that have been raised with these pre and post control groups. And that future research should just examine this perhaps in more detail or just be careful in terms of when they’re designing their studies that they are using the most effective design.

Mickes: Yeah. Okay. So those are your main recommendations.

Hughes: I think so yeah, mostly in terms of study design. Um, I know we touched on the intervention length as well and our findings do support the use of these shorter term interventions. And we do also recommend future research rather than focusing strictly on these structured mindfulness courses that they do pay more attention to these little inductions and just yeah, not, not completely discredit them. They, they are useful and they, they do elicit beneficial effects that we’ve seen in our review and we’ve seen across some other studies too. And so yeah, I think research should definitely consider these shorter interventions as well as longer ones or perhaps this mid-range too, somewhere in the middle.

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: Seems to be beneficial. And then in terms of creativity task, we did have one recommendation here and that was for future studies to select a creativity task with minimal overlap between convergent and divergent processes.

Hughes: So where they can, if they choose a task that has minimal overlap, it will ensure, I guess a bit of validity across results and limit this uncertainty in grouping. So it’ll be able to draw firmer conclusions as to how mindfulness is affecting a certain type of creativity.

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: We’ll understand that a little bit better rather than having just any creativity tasks or just a, a broad creativity task with lots of trials because it could be that in, well, participants are approaching each trial differently even. So what we really need to understand and ensure is that the task we’re using, we understand how the participants are approaching it, whether that they’ve approached it in an analytical way or in a step-by-step, or they’ve just had a light bulb moment where it just came into their mind. Perhaps getting that feedback after each trial will be useful and helping us determine first how they solved it and then how any effects of mindfulness might have influenced that particular solving process.

Mickes: Right. Did you look for publication bias?

Hughes: Yes, we did. So we did look at publication bias. Off the top of my head, I think we did see some publication bias, which I think is expected in most meta analytical reviews, to be honest. We did find some and we used trim and fill methods to, to tackle that, to ensure that our data was, was, was appropriate for the meta analysis that we were conducting. So yes, it’s something we did encounter. Something I wasn’t, well, we weren’t too surprised about.

Mickes: Yeah.

Hughes: I think the heterogeneity as well, we did see quite a large amount of that, the differences across studies as well, which I guess is so difficult when it comes to any type of review. Pulling everything together when they’re so different can be really difficult and challenging. So that’s something we did see and we tried to tackle that with our moderator variables. We tried to see where the biggest differences were.

Mickes: Mm-hmm.

Hughes: And in our case, it, it was the length of the intervention and the type of creativity task and then this, this study design as well. But of course there are lots of other differences, individual differences, perhaps age that could have also influenced findings. But I mean, there’s only so much you can do in, in one analysis and we, we couldn’t have included loads of moderator variables. But I think again, moving forward, perhaps those things are something worth considering as well. So individual characteristics.

Mickes: Yeah. Right. Oh, that sounds exciting. There’s still so much to understand about what mindfulness is doing and this is a good step toward that. Do you have anything you wanna say that I didn’t ask?

Hughes: I think we addressed everything I’d like to say in terms of our explanations of, of the relationship and, and ultimately I guess that yes, mindfulness does seem to be beneficial for creativity and I think that would be a good, a good note to end on.

Mickes: That is perfect to end on. We’ll end there then. Thank you again, Zoe.

Hughes: Perfect, thank you Laura for having me.

Concluding statement

Kosovicheva: Thank you for listening to All Things Cognition, a Psychonomic Society podcast. If you liked this episode, don’t forget to follow the channel using your favorite podcast player or app. All members of the Psychonomic Society receive free access to our seven journals and are invited to attend our annual conference at no charge. Learn more and become a member by visiting us online at http://www.psychonomic.org.

Featured Psychonomic Society article

Hughes, Z., Ball, L.J., Richardson, C. & Judge, J. (2023). A meta-analytical review of the impact of mindfulness on creativity: Framing current lines of research and defining moderator variables. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-023-02327-w