If you are a cognitive psychologist, you have probably used the Deese-Roediger-McDermott paradigm in your lectures as a false memory demonstration. If not, try the demo now by reading the following list. Try to remember the words for a memory test (don’t take notes!):

- soda

- heart

- tooth

- tart

- taste

- sour

- bitter

- good

- sugar

- candy

- nice

- cake

- pie

- chocolate

- honey

Now, take the following memory test: Did you read the word “sweet”?

If you are convinced that “sweet” was indeed in the list above, you are experiencing a false recognition error. In most circumstances, more than 50% of my class would confidently state that they had read/heard the word “sweet”. This class demonstration always gets students intrigued about the reconstructive nature of our human memory system. Memories are not like a photograph, but rather, it is a reconstruction of the past each time we try to bring an episode to awareness. In the example above, “sweet” is the critical lure (CL), or the theme-word, that many participants end up misremembering. The key question, however, is why this false memory is so commonly induced and what causes it? Is this false memory a result of an automatic, involuntary process, or is it a product of a conscious memory search?

In an article recently published in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, Jerwen Jou and Mark Hwang (pictured below) borrowed the DRM paradigm to test an interesting effect called the “dud” effect found in eyewitness testimony research. Recent studies have shown that when highly dissimilar characters (duds) to the suspect are put in an eyewitness lineup, the rate and confidence for selecting the suspect goes up. Take a real-world example to further illustrate this point. If you witnessed a White man committing a robbery and were later asked by the police to identify the culprit from a lineup, you are more likely and confidently to identify a White innocent man from among several individuals (fillers) of other races than from among several fillers of White men. This blog has touched on this topic before. Because the other-race fillers are very different from the suspect, hence called “duds,” they increase the similarity of the only White innocent man to the suspect, which in turn increase the likelihood of wrong identification.

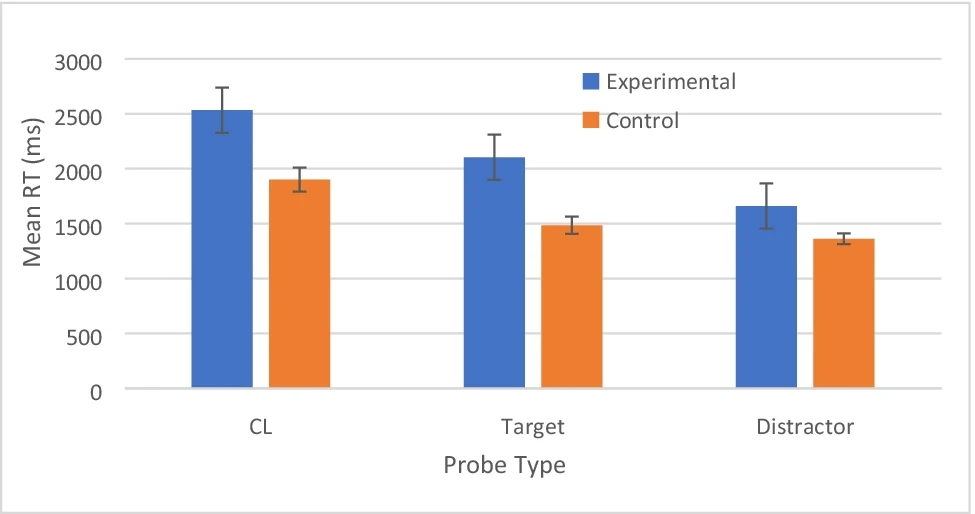

The authors manipulated the number of similar and dissimilar probes in their DRM test lists and found that participants were indeed more likely to falsely recognize the critical lures when fewer studied probes were presented. Participants also appeared to have an increased RT while making these false memory errors. This account is contrary to the traditional cognitive account of interference and spreading activation, which suggests that false memory is generated by an involuntary process, and exposure to related concepts increases its rate. Also, according to traditional cognitive theories, false memories usually occur when we make quick, automated decisions.

However, Jou and Hwang (2022) found that this is not always true, as their study revealed that a slow, monitored process with the majority of the probes being highly implausible actually increased false memory errors, as shown in the figure below.

Using the DRM paradigm as a parallel, they found that if participants studied bed, tired, night, dream, blanket, snoring, etc.(but without the word sleep), and were later asked to recognize the studied words among bed, wake, tired, sleep versus among desk, clothes, grass, sleep, they were more likely to falsely recognize sleep as a studied word in the latter, rather than in the former, lineup of the test words. This heightened false recognition is due to their conscious deliberation, rather than memory confusion caused by the similarity among the test words – thus challenging a traditional perspective long-held by cognitive psychologists.

Let’s end this article with a funny eyewitness lineup video – enjoy!

Psychonomic Society article featured in this post

Jou, J., & Hwang, M. (2022). A memory-interference versus the ‘dud’-effect account of a DRM false memory result: Fewer related targets at test, higher critical-lure false recognition, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-022-02083-3