Each year around Thanksgiving I am faced with the same dilemma: nibble on a small amount of snacks as the food is being prepared, or delay gratification for the glorious full plate of edible treasures. Although this may seem trivial, allow me to set the stage:

Imagine that it’s the morning of Thanksgiving. Your refrigerator is stocked with various foods to be dressed. As you navigate around the kitchen where various loved ones are preparing their own tasty contributions, they are hounding you to taste this and try that. You are well aware that you can either take small amounts of samples now to satisfy your roaring belly or you can wait until dinner is served and enjoy a large plate of good home cooking. What do you do? And once you’ve made decisions about food, how might hunger impact your decision for shopping the next day during “Black Friday”?

From a cognitive perspective, my preference for instant gratification (i.e., eating small snacks now) over waiting for dinner is known as delay discounting. Delay discounting refers to the depreciation in the value of a reward with respect to the time in which the reward is received. A person who shows delay discounting will discount the value of a larger reward that will be available later, and will instead prefer a smaller reward sooner.

Although delay discounting is often associated with impulsive behaviors, such as gambling and addiction, it is also linked to physiological states like hunger. An interesting question that remains is: does hunger also lead to delay discounting of non-food items?

In a recent article published in the Psychonomic Society journal, Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, researchers Jordan Skrynka and Benjamin Vincent (pictured below) investigated how reward valuations for food and non-food items change under the undesirable psychological state of hunger.

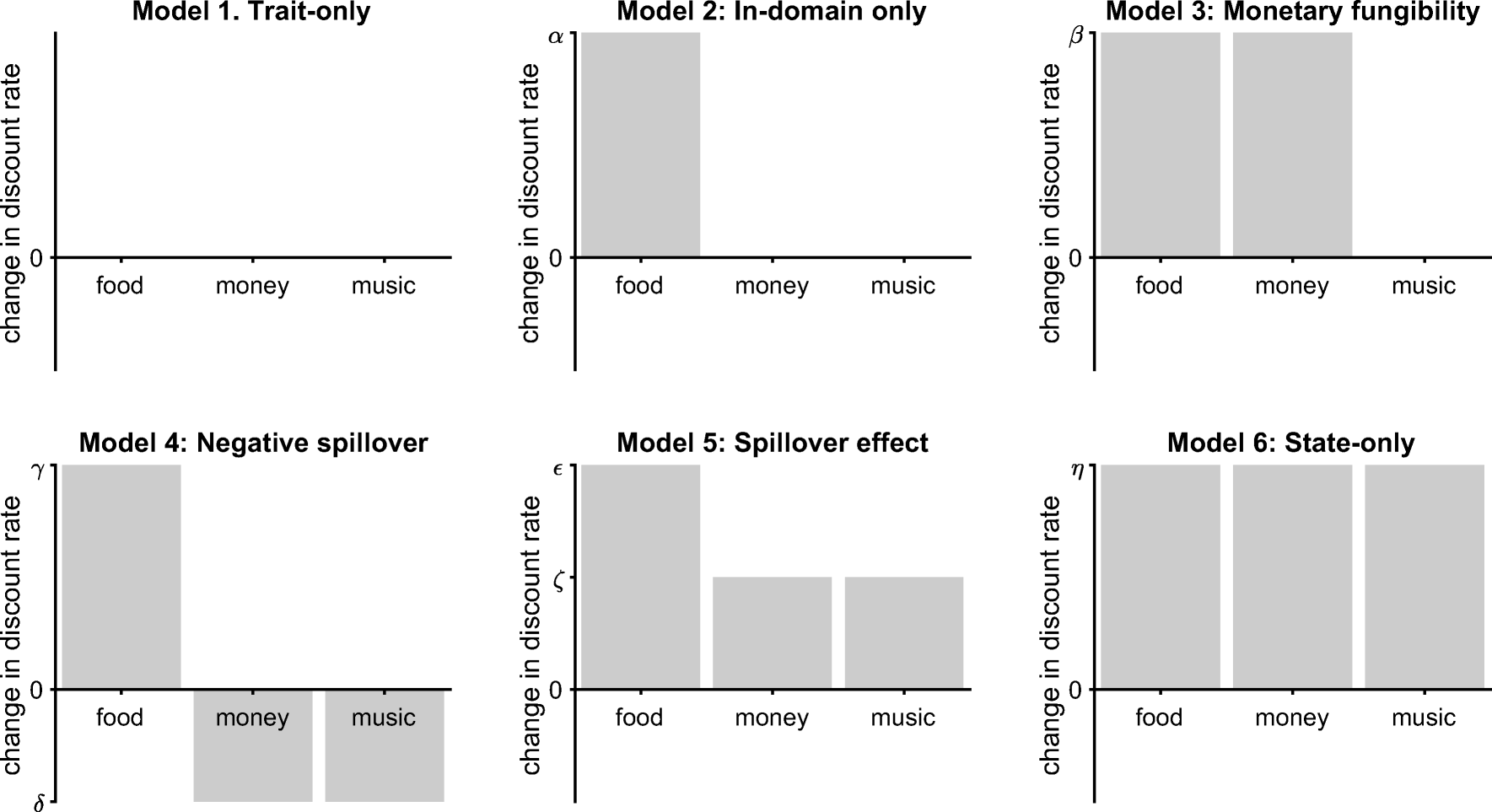

In the article, the researchers explored six possible discounting behaviors that might result from hunger:

- Trait only model: hunger will not affect delay discounting of food or non-food items.

- In-domain only model: hunger will affect discounting for food items which could satisfy hunger (produce a desired state change), but not non-food items.

- Monetary fungibility model: hunger will increase delay discounting of food items and money because money can indirectly satisfy hunger (buying food can produce a desired state change).

- Negative spill over model: hunger will increase delay discounting for food, but decrease discounting for non-food items.

- Spill over model: hunger will increase delay discounting for food items, and cause a small increase in discounting of non-food items.

- State-only model: when comparable, hunger will equally affect discounting for all items (i.e., food and non-food items).

To assess these six possible outcomes, the researchers measured discounting for three commodities: food, which directly satisfies hunger, money, which can indirectly satisfy hunger, and music via song downloads, which has no direct impact on hunger. The figure below shows predictions for discounting behavior for each of the three commodities under the six models.

In the experiment, participants were tested either first in the hunger condition (session 1) and then in the control condition (session 2), or vice versa. Individuals in the hunger condition were instructed to fast for 10 hours prior to being tested. Individuals in the control condition were told to eat within the 2 hours of being tested. For each session, participants’ blood glucose levels were measured, followed by completing a subjective hunger questionnaire, and then a delay discounting task.

In the discounting task, participants completed 35 discounting trials where the wording was, “You can have [X] chocolate bars now, or [X*d] chocolate bars in [Y hours/days]”.

In this example, X refers to the quantity of the reward, d refers to the magnitude increase in X to denote a larger later reward, and Y refers to the time delay for the larger later reward. For example, a sample trial sentence might read, “You can have [X=5] candy bars now, or [d=2; X*d=10] candy bars in [Y=4 hours]”. The time delay varied from 1 hour to 1 year and the later value was always fixed (20 pounds of money, 20 song downloads, and 10 chocolate bars). Bayesian computational approaches were used to determine immediate reward amounts and time delay.

Discounting behavior was assessed using a hyperbolic discounting function that measures the subjective value of a reward given the magnitude of the reward change and the time delay between award amounts. In other words, it’s a measure of how much people value the reward amounts given the increase of the later amount and the amount of time before the later reward.

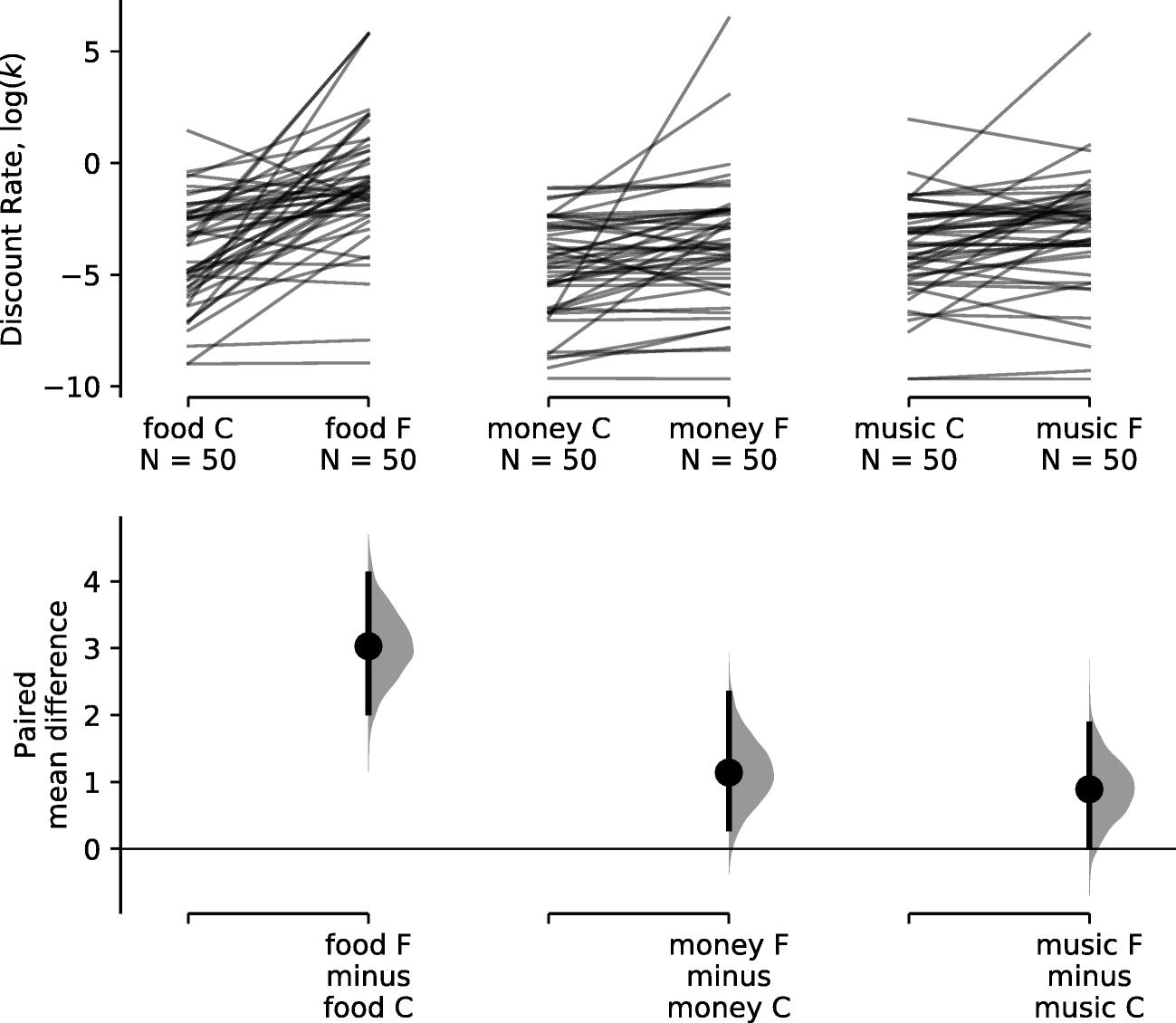

The results of this experiment were interesting! First, the 10-hour fasting procedure induced hunger, evidenced by increased subjective hunger ratings on the hunger questionnaire. Discounting (preferring the smaller sooner reward) was lower in the control condition than the hunger condition for all commodities (upper panels in the figure below). In addition, there was a greater increase in discounting for food compared to money and music (lower panels in the figure below).

Lastly, the visual and quantitative analyses of the data strongly favored the Spillover model compared to all others. This means that hunger can bring about substantial delay discounting (preference for smaller sooner rewards) for food and this can carry a 25% spill over to non-food items, like money.

Given the results of this study, my advice to all the shoppers in the world, do not go to the grocery store (or any store for that matter) on an empty stomach! You might wind up settling for smaller rewards sooner, rather than larger later rewards if you’re hungry!

Featured Psychonomic Society article:

Skrynka, J. & Vincent, B. (2019). Hunger increases delay discounting of food and non-food rewards. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, DOI 10.3758/s13423-019-01655-0.