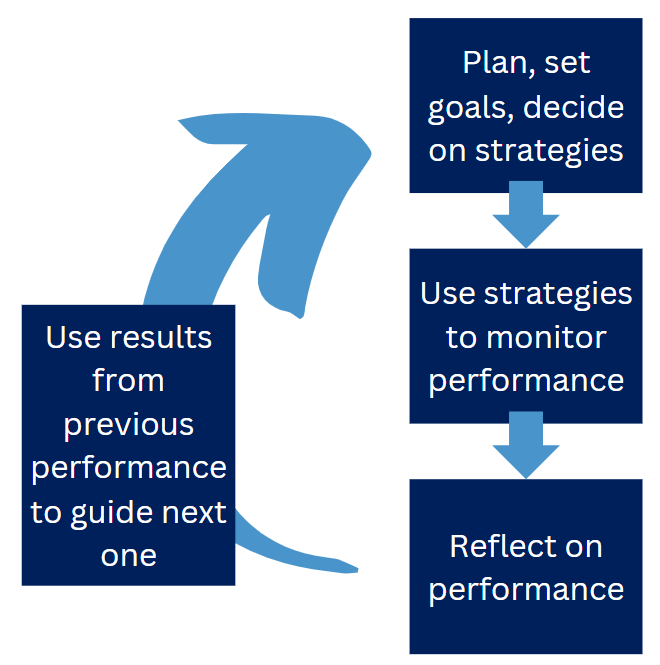

With the start of a new term underway, many students and educators are likely in the process of creating goals for a successful term and developing plans toward achieving those goals. Students’ goals might include earning a certain grade in their course or mastering the course material. To achieve these goals, students may create a study plan including when and how they will study (e.g., what strategies they will use), monitor their ongoing progress, and reflect on performance and feedback. In a similar vein, educators’ goals likely revolve around finding ways to best facilitate their students’ learning. Plans for achieving such goals may include updating their course preps, trying out new activities, or modifying the techniques they use while teaching. They might include measures that help them determine how well they have met their goal, such as ongoing evaluations of student understanding.

Creating goals, developing plans to meet them, and monitoring learning are all essential components of being a strategic self-regulated learner. In this blog post, I’ll focus on monitoring – students’ ability to evaluate their learning, which is necessary for ensuring that they are making progress toward their goals.

How well can students evaluate their own learning? Unfortunately, an abundance of research has demonstrated dissociations between students’ subjective evaluations of their learning and objective measures of it. That is, some educational practices can increase students’ estimates of how much (or how well) they have learned without leading to parallel improvements in their actual learning, an effect referred to as an illusion of learning.

Lectures that make the material feel fluent can cause illusions of learning

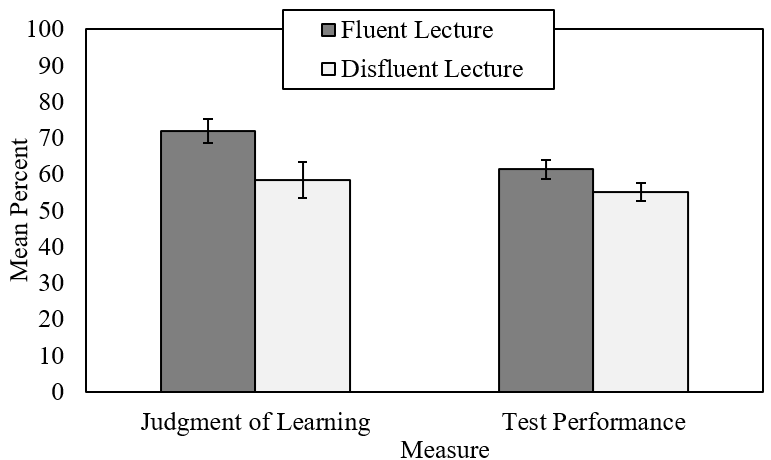

In a recent review, my co-authors (Dr. Shana Carpenter and Dr. Uma Tauber) and I detailed many such illusions of learning and discuss their impacts on various educational outcomes. As an example, students tend to place a high emphasis on the way that their instructor delivers a lecture, thinking this factor influences learning even when it typically has little-to-no impact. This was evidenced in a recent study in which participants watched an instructor deliver a lecture on an educational topic, took notes, and then were tested on the content. In one version of the lecture, the instructor presented the information in a fluent manner (i.e., standing straight, making eye contact, presenting enthusiastically). In another version, the instructor presented the information in a disfluent manner (i.e., hunched over a podium, avoiding eye contact, reading from notes). Most importantly, although the presentation style differed between versions, the actual educational content was identical.

The key question was, would educational outcomes differ depending on the presentation style of the lecture? Regarding objective measures of learning – which included test performance, quantity of notes, and quality of notes – lecture fluency had no impact. However, lecture fluency did impact students’ subjective evaluations of their learning. Students who watched the fluent version of the lecture judged their own learning to be better and rated their instructor as more effective compared to students who watched the disfluent version of the lecture – demonstrating an illusion of learning.

Learning strategies that make the material feel fluent can cause illusions of learning

Similar illusions of learning are evident when students prepare for course exams. Nearly anyone who has taught a course has likely had the experience of a student coming to their office after receiving their grade on an exam. In my experience, these situations usually follow a relatively prescribed pattern. First, the student expresses concern over their grade, usually indicating that they performed significantly worse than they had anticipated. Next, I will ask them to tell me how they prepared for the exam – how did they study, how often did they study, when did they start studying. There is usually some variability in students’ responses to this question, but the consistent pattern that emerges is that students report using study strategies that make material feel fluent and familiar but are relatively ineffective for promoting lasting learning.

For instance, in these conversations, a common strategy that students report using is rewriting their notes. This strategy tends to be a relatively passive strategy that is akin to simply rereading the notes or a textbook. Passive re-exposure to material does not typically produce large learning gains. However, students often tell me that this strategy feels productive, because they are making tangible progress while rewriting their notes. These feelings, unfortunately, are not good indications of learning. Rewriting notes (or rereading) produces a similar sense of fluency as in the instructor fluency study described above. It is easy to remember information that is sitting right in front of you. Thus, when students evaluate their learning while using this strategy, they tend to overestimate their knowledge. Situations such as these are what often lead to students’ surprise when they perform poorly on an exam where they need to retrieve information from their memory.

What can students do to avoid illusions of learning?

1. Use empirically-supported learning strategies (i.e., desirable difficulties).

Strategies like self-testing and spacing (i.e., distributed practice) make learning feel more difficult and less fluent, promoting memory and improving evaluations of knowledge.

When studying for class, students should regularly test themselves on the course concepts. Flash cards are a great way to facilitate this. When using this strategy, it is important that students avoid cheating themselves by looking at the answers before they have tried remembering the full answer on their own – after all, the process of retrieval is what leads to accurate evaluations and lasting learning. When first starting to learn a new course concept, this process will feel difficult and uncomfortable, especially because it can involve failure (e.g., when material is not accurately remembered). However, this is a desirable difficulty because it can facilitate elaboration and create more distinctive memories for the to-be-remembered information, which will ultimately improve learning. Retrieval practice also benefits learning because it mimics what students will typically need to do on their course exams (i.e., retrieve information from only their memory).

Students should also spread their study sessions out over time and test themselves on the same concepts in multiple study sessions. Even if something appeared to be well learned in an initial study session, it is possible that that information will be forgotten before the next study session. Multiple testing opportunities over time will help increase the strength of the memory and increase the likelihood that it will be remembered on a later test. As well, studying material at different times may help students come up with new examples that can serve as new retrieval cues to help them remember the information later.

2. Delay metacognitive evaluations of learning.

People are more accurate at judging their own learning when those judgments are made at a delay compared to if they are made immediately after learning. Immediately after learning, learners tend to rely on the sense of familiarity they have with the material to inform their judgments. Because the material has just been learned (i.e., it is fresh on the mind in working memory), it feels very familiar, and that will inflate judgments of learning. By contrast, allowing some time to pass between initial learning and evaluations of learning will improve the accuracy of learning judgments and ultimately help students make better study decisions.

What can educators do to help students avoid illusions of learning?

1. Provide students guidance on how to study effectively.

Survey estimates suggest that less than 40% of students study the way that they do because a teacher taught them to study that way. Instead, many students develop their study strategies on their own, using strategies that appear, to them, to be effective for learning. The research on illusions of learning, however, suggests that students may not always know what is best for promoting lasting learning. Thus, one way that educators can help is by giving students guidance on how to study effectively. Having these conversations early in the course can help give students the tools to be successful learners.

2. Model effective learning strategies during class.

In addition to encouraging students to use effective learning strategies, educators can structure their courses in ways that encourage the use of such strategies in and out of class time. For instance, asking students questions during class can serve the same purposes as self-testing with flash cards. Informally quizzing students in this way can help them identify gaps in their knowledge and promote learning of that information. Educators can also provide students with opportunities to reflect on their learning experiences, asking them to answer questions such as, “What strategies worked well for me as I prepared for the exam?” and, “What study habits will I try to improve upon for the next exam?”

Take Home

Effectively monitoring one’s learning is an important skill for students to master so that they can achieve their academic goals. Illusions of learning can undermine this skill, leading students to be overconfident in how much they have learned. Being aware of the things that can cause illusions of learning can help students better plan their learning and use more effective study strategies. Together, this can help to safeguard from the negative repercussions of overconfidence.

Recommended Reading:

Carpenter, S. K., Witherby, A. E., & Tauber, S. K. (2020). On students’(mis) judgments of learning and teaching effectiveness. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(2), 137-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2019.12.009