TikToks are short videos that typically show a set of movements. Doing the Macarena requires remembering a sequence of movements to make up the dance.

Our communications are full of hand gestures and body movements. These “co-speech” hand gestures are meaningful and often relate to the content of our speech. Co-speech gestures enhance the understanding of a listener, help a speaker “find the right word”, facilitate learning new knowledge (such as a mathematical concept or a foreign language), and help people retrieve previously stored information.

Gestures that are related to the information to be remembered enhance the memory of that information – a construct called the “enactment effect”. For example, if a participant acts out digging with a hoe, the participant will remember “hoe” more often when asked at a later time, if allowed to “dig with a hoe” at retrieval. The enactment effect doesn’t work if the participant has to “eat with a spoon” instead of “dig with a hoe” at retrieval.

Other research has shown that unrelated motor activities can sometimes enhance memories while in other contexts they inhibit memories. This phenomenon has been discussed within the context of a theoretical gesture production framework. This account suggests that gesturing during speech activates the motor system, which will also activate a perceptual state that may trigger a thought or memory.

One possible mechanism for this framework that has been tested is the direct-activation account, which suggests that unrelated motor movements can sometimes enhance recall but at other times inhibit it. To test the direct-activation account, a typical experiment requires participants to watch a video portraying an actor use a gesture, or not, that accompanies a phrase. For example, if the phrase is “playing the piano” the video shows an actor saying the phrase while she curves and wiggles her fingers (as in the left image below) or shows the actor saying the phrase without making a gesture (as in the right image below).

For studies in which the direct activation account is tested, participants do a variety of motor activities. For example, while viewing a video of an actor playing the piano for the first time (the encoding phase), participants may be asked to 1) engage in the same piano finger movement, 2) not engage in any hand movement, 3) tap out a specific rhythm with their hands, or 4) rhythmically tap their toes. When asked to recall action sequences experienced during the encoding phase, participants either repeat the same motor action experienced during encoding, produce a different motor action, or produce no motor action.

The best recall occurs when participants engage in the same motor actions at recall that they either observed performed (the actor gesturing piano playing) or were able to perform when first exposed (participants themselves gesturing piano playing). If participants were asked to do an irrelevant hand motor action at encoding or at retrieval (tapping), recall was lower. Interestingly, engaging in foot motor actions at either encoding or retrieval does not harm or improve recall.

The question explored in a recent article by Halvorson, Bushinksi, and Hilverman published in the Psychonomic Society journal Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics was: What would happen to recall of action sequences if encoding specificity (i.e., when items/events at encoding and retrieval match) was considered during the use of irrelevant hand-based motor actions?

Halvorson and colleagues investigated whether irrelevant motor actions were as effective as meaningful gestures if participants were allowed to produce the same action at encoding and at retrieval. That is, if the participant rhythmically tapped during the viewing of a person saying “playing piano” with or without a gesture and then tapped again when recalling action sequences observed during encoding, would recall be facilitated if the participant was mismatched between encoding and retrieval phases (i.e., did not do the same motor action from the encoding phase)?

Their reasoning was that despite the motor action being irrelevant to the action sequences they were supposed to learn, having a match in motor action at both encoding and retrieval would create a consistent set of cues that were included with the stimulus action stored during encoding.

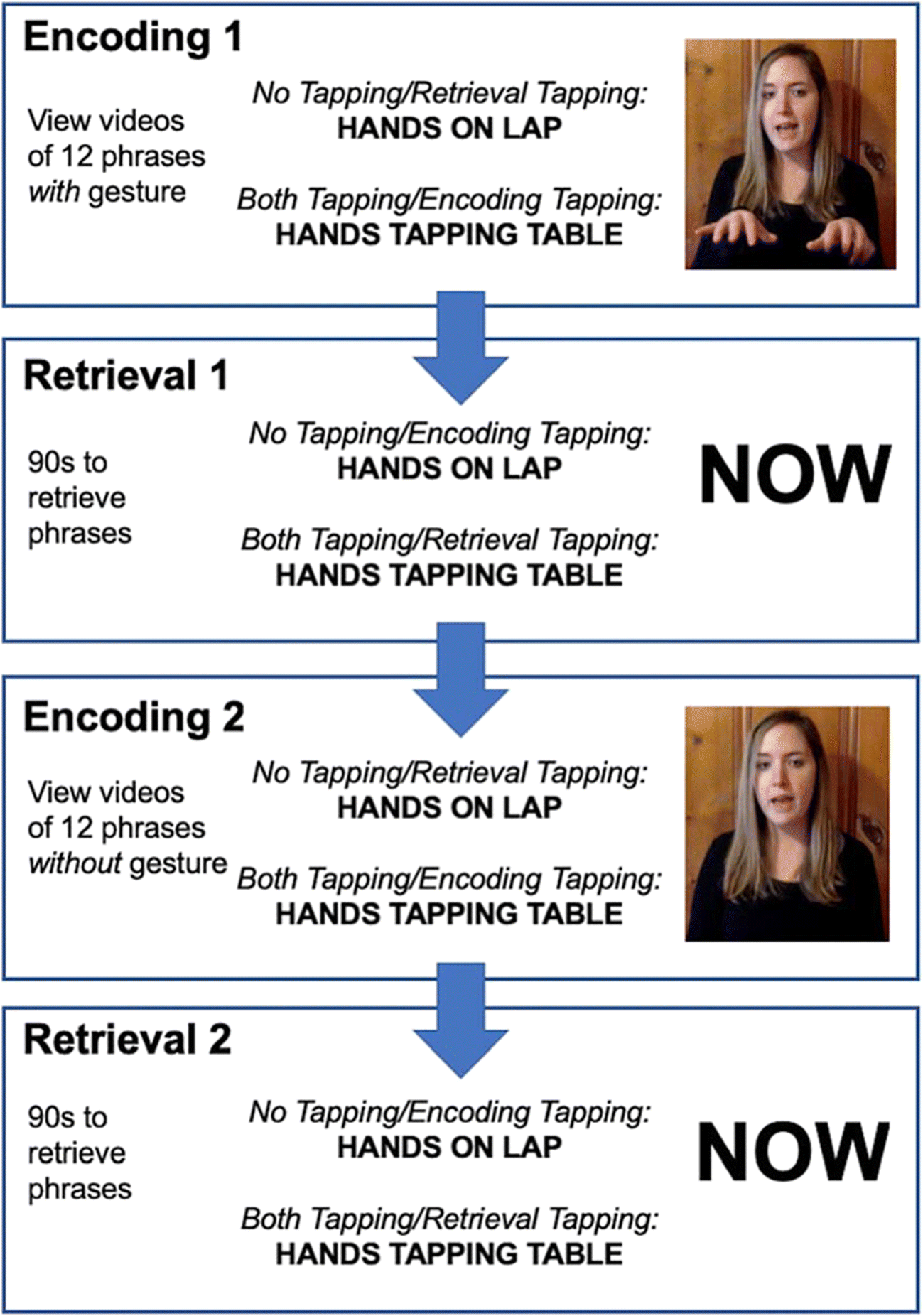

To explore this question, participants produced irrelevant motor actions (tapping with hands) that did not correspond to the action phrases observed across different videos with or without gestures. As shown in the image below, participants experienced one of four conditions for two sets of videos that were counterbalanced (with relevant gesture and without relevant gesture): (1) match control – no tapping at either encoding or retrieval, (2) match experimental – tapping at both encoding and retrieval, (3) mismatch experimental – tapping only at encoding but not retrieval, or (4) mismatch experimental tapping only at retrieval.

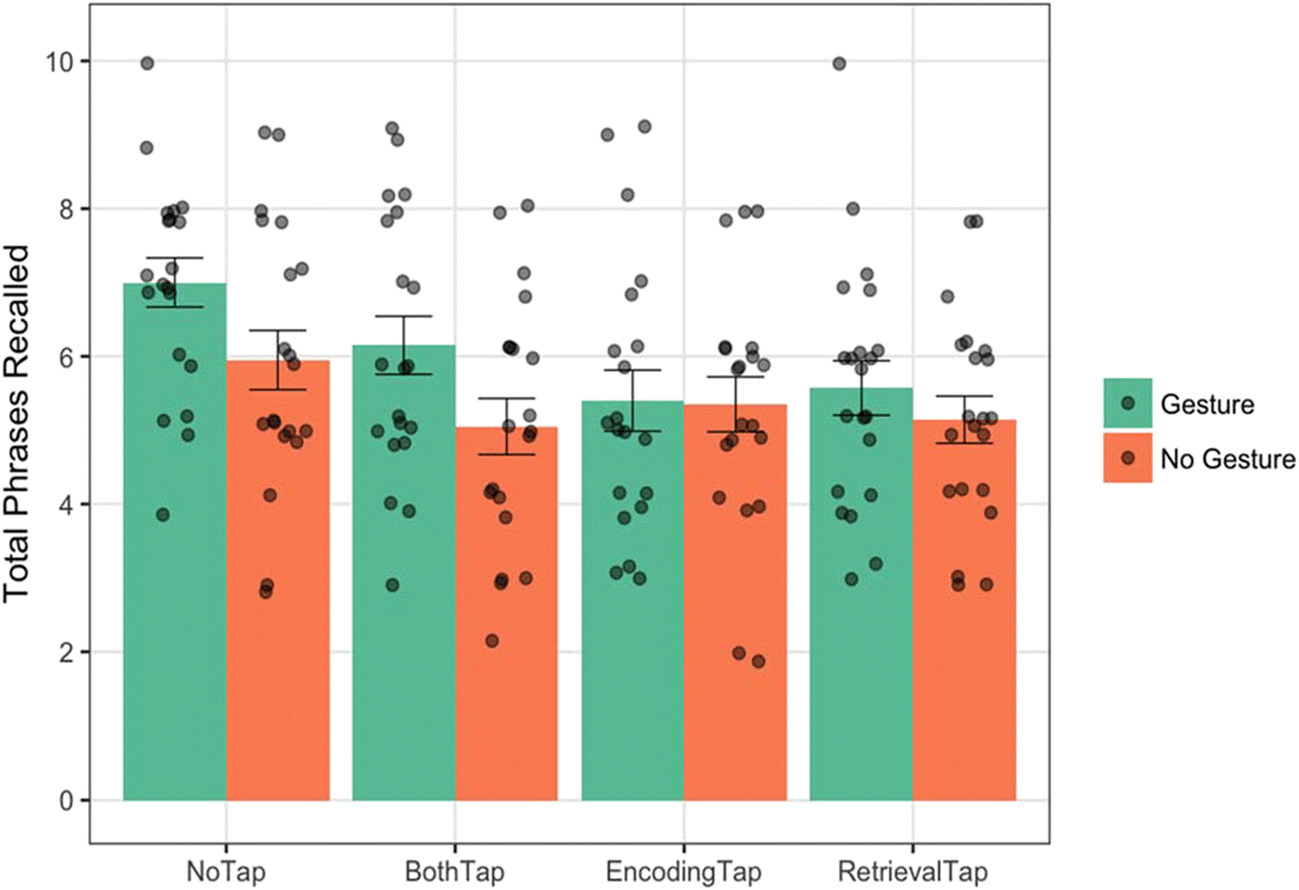

The results supported the encoding-specificity account with the best results for matched conditions at encoding and retrieval (both, match-no tapping and match-tapping).

As shown in the figure above, recall was best facilitated when the irrelevant motor action was not performed at all (No Tap and Both Tap). Performance for mismatched conditions at encoding and retrieval illustrated that recall accuracy was lower.

Interestingly, the presence of relevant motor actions in the video at encoding (i.e., the model gesturing playing the piano when saying piano playing), as shown by the “Gesture” green bars facilitated recall accuracy for both matched conditions over above the videos in which there was no accompanying gesture, as shown in the orange bars.

The presence of a gesture was especially helpful when participants produced paraphrased responses. For example, participants were given the phrase “whisking eggs” with a relevant motor action of “whisking eggs” but remembered “beating eggs” or “ stirring eggs” during the recall test, instead of “whisking eggs”.

The authors pointed out that these results may be very helpful for classroom instruction, therapeutic settings, and other learning environments. If we could find ways to facilitate encoding and retention by pairing motor actions with content, we might be able to increase the efficiency of learning while also making it fun. While this idea isn’t necessarily new, it could encourage people to try things they aren’t normally comfortable with by pairing it with things they love such as having your teen make a TikTok for human geography terms or performing the Macarena to remember the list of items you need at the grocery store.

The Psychonomic Society article covered in this post:

Halvorson, K. M., Bushinski, A. & Hilverman, C. (2019). The role of motor context in the beneficial effects of hand gesture on memory. Attention Perception & Psychophysics, 81, 2354–2364. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-019-01734-3