Have you ever met anyone who dislikes magic tricks? No, me neither. Magicians and magic tricks seem to be universally appreciated in western culture. Whether it is at corporate events, kids’ birthday parties, or simply at the pub down the road, magic is fun and attracts an appreciative audience of all ages.

One question that is invariably at the top of everyone’s mind after watching any magic trick, is “how did you do it”? Presumably you didn’t really saw that woman in half?

The answer is never obvious, even in very simple tricks, such as this one:

The magician taps the coin once, twice, … and by the third tap it has seemingly vanished.

A recent article in the Psychonomic Society’s journal Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics investigated the cognitive processes underlying magic tricks. Researchers Anthony Barnhart, Mandy Ehlert, Stephen Goldinger, and Alison Mackey focused on the way in which magicians suppress our visual attention to make their tricks work.

For example, magicians suppress our attention so we fail to notice that the coin is thrown from the open palm into the hand holding the wand right before the wand strikes a third time. (Watch the video again and chances are you still won’t see it.)

The reason we fail to see the coin being moved is because our attention has been entrained by the rhythmic tapping. As a result, the sleight which occurs during an attentional “trough” in between taps goes unnoticed. Magic, it turns out, is simply an application of the cognitive science of attention.

This was already known during the 19th century, when Max Dessoir noted that:

“If we count ‘One! two! three!’ before the disappearance of an object, then the actual disappearance must take place before and not just at the ‘three’; for while the attention of the audience is fixed upon ‘three’ anything taking place at ‘one’ or ‘two’ entirely escapes it.”

In the laboratory, such entrainment has been observed repeatedly. For example, detection rates for subtle visual targets have been found to increase when they were presented in phase with a rhythmic visual entrainer. However, less is known about cross-modal entrainment, which is what is at the heart of the vanishing-coin trick: we fail to see something because we are entrained to a rhythmic sound.

Barnhart and colleagues asked whether a rhythmic auditory input stream would entrain visual attention. In their study, participants had to detect a subtle visual stimulus embedded in noise. The figure below shows the stimulus display before (A) and after (B) the target has been presented:

Can you spot the target in panel B?

If not, then the next figure might help in which the target is highlighted:

I did mention that the stimulus was subtle.

On each trial, participants monitored the visual noise stimulus while listening to a sequence of 150-ms tones at either 750 or 900 Hz, one of which was an “oddball” of the other frequency. So people might hear a number of 750-Hz pulses with one 900 Hz oddball, or vice versa. The sequence of tones was either slow (a tone every 1.5 seconds) or fast (one every 650 ms). Orthogonally to the speed manipulation, participants were either instructed to attend to the auditory sequence or to ignore it.

The manipulation of greatest interest was the timing of the visual dot probes. Probes were either temporally aligned with the onset of a tone, offset by 25% or by 50% of the entraining frequency on a given trial.

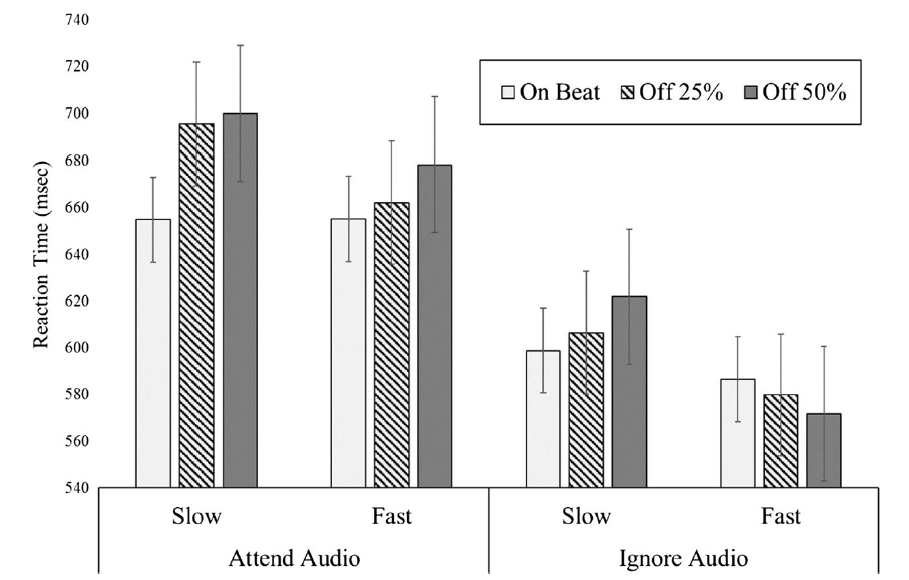

The main results are shown in the next figure, which displays response times to detect the visual probe for all conditions:

It is clear that participants responded to the probes more quickly (and more accurately, although the data are not presented here) when they were aligned in time with the onset of a tone in a rhythmic stream. Participants responded more slowly when the probes were misaligned with the tones.

Translate the probes into coins and the above figure shows the workings of a magic trick.

This conclusion is, however, accompanied by one caveat: the entrainment occurred only when the rhythm was relatively slow. However, at the slow speed it generalized across both attentional conditions: it did not matter whether participants were actively listening or were ignoring the rhythmic stream—as one would be likely ignoring the tapping of the magic wand.

In a second, nearly identical experiment, Barnhart and colleagues changed the temporal sequence of the tones from being invariant (i.e., a steady rhythm) to being either slowing or accelerating. On a random half of trials, the tones were presented increasingly quickly, and on the other half the sequence slowed down.

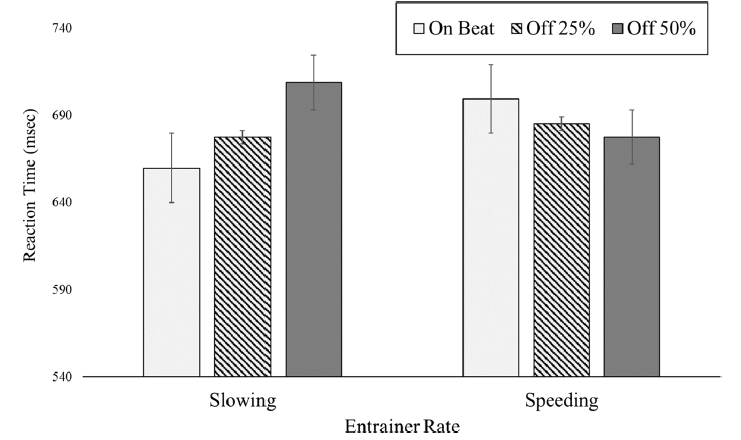

The results are shown in the next figure (collapsing across attention condition):

The results are compatible with the idea that people rely on the most recent interval between tones to anticipate when they should deploy attention for the next one. In the slowing condition, this estimate would lead to premature deployment (as each additional tone is delayed further), but that deployment would still benefit a—slightly delayed—event. By contrast, participants in the speeding condition would deploy attention too late (as each additional tone arrives sooner than anticipated), thus being slower to detect targets on the beat, but quicker for those that were delayed (and hence accidentally fell into the anticipated window).

The data of Barnhart and colleagues have clear implications for magicians: keep the distracting speech or sounds steady when you get ready to hide your coin.

The data of Barnhart and colleagues also have clear implications for cognitive scientists: go and watch a few magic shows. Understanding the methods of magicians may well reveal additional attributes of our cognitive systems.

And right on cue, here is the conference for precisely that.

Psychonomics article featured in this post:

Barnhart, A. S., Ehlert, M. J., Goldinger, S. D., & Mackey, A. D. (2018). Cross-modal attentional entrainment: Insights from magicians. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 80, 1240-1249. DOI: 10.3758/s13414-018-1497-8.