As you try to make sense of this sentence, do you find yourself looking at individual letters, or processing each word automatically? If you are an expert English reader, you probably said the latter.

Evidence suggests that at least some word recognition occurs due to holistic processing, or perceptually integrating letters into a unitary whole. The same is true for our recognition of faces – instead of taking in each facial feature individually (e.g., eyes, nose, mouth), we tend to integrate them during perception.

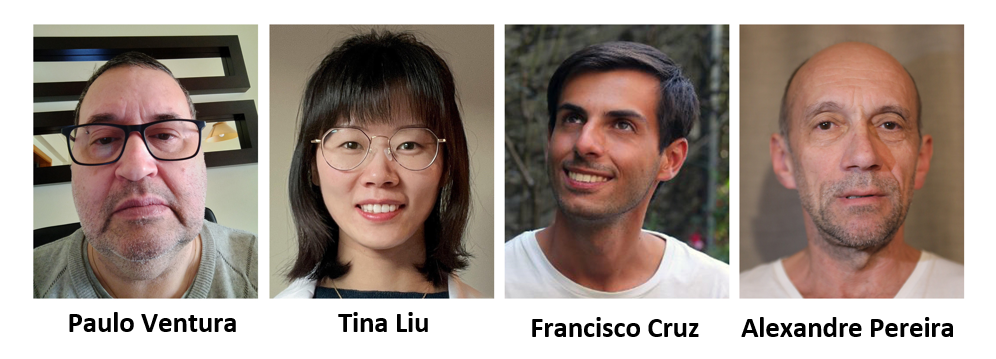

Holistic processing occurs for both words and faces, but does such processing rely on a shared mechanism? This was the question that Paulo Ventura and colleagues (pictured below) set out to answer in a recent paper published in the Psychonomic Society journal Memory & Cognition.

The Composite Task and prior outcomes supporting holistic processing

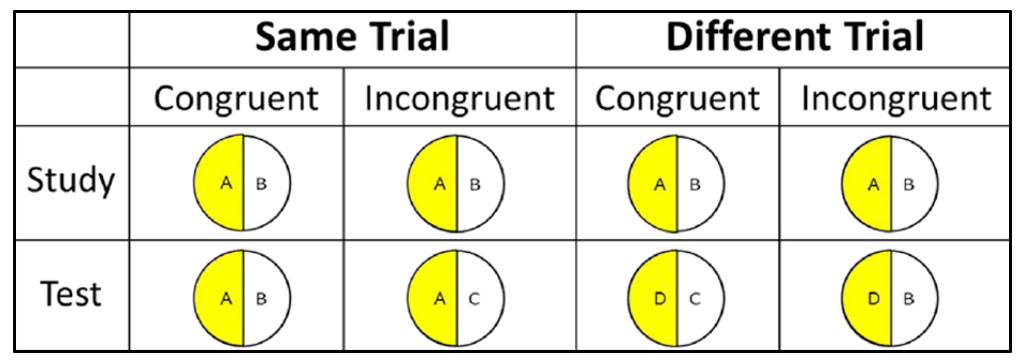

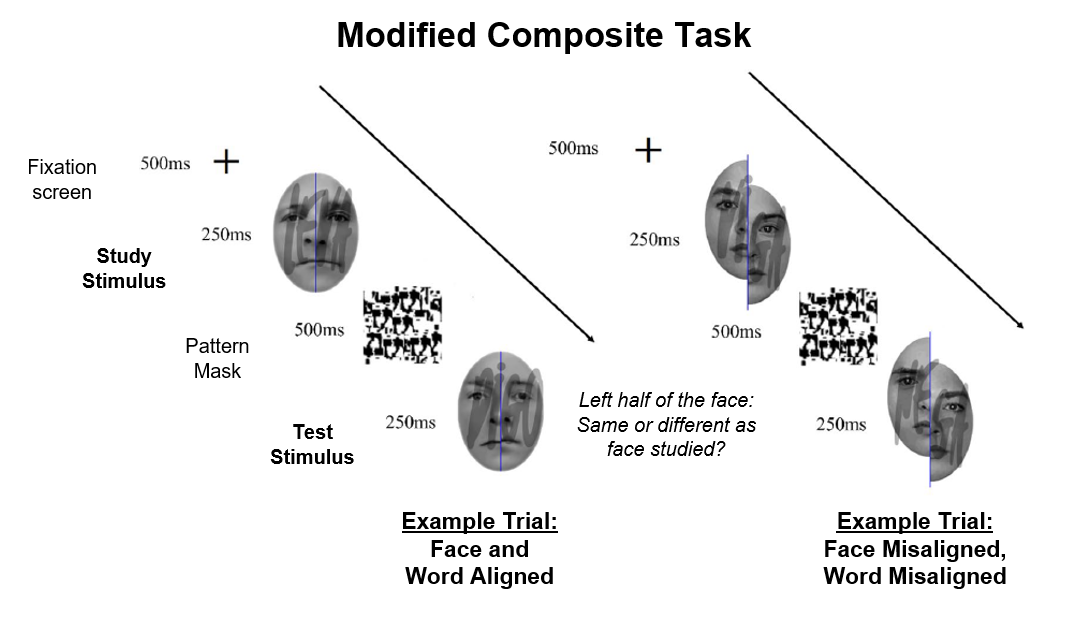

To understand what the authors did to answer their question, we first need an understanding of the composite task – a perceptual task commonly used to assess holistic processing of faces. In this task, illustrated in the figure below, participants undergo multiple trials in which they are briefly shown a face (composed of two sides) to study, then shown another composite face at test. At test, participants make same-different judgments – that is, they judge whether the left side of the face matches the left side of the face they saw during study.

Prior outcomes using this task support holistic processing of faces. First, consider the congruency effect: The right half of the composite face is irrelevant to making accurate same-different judgments about the left side of the face, but participants generally perform better (i.e., make fewer errors) when the two sides of the faces presented during study are congruent with those presented during test compared to when they are incongruent. For example, on a trial in which a participant should make a same response (“same trial”), they would perform better on trials in which both the left and right sides of the face composites are the same during study and test compared to trials in which the left side of the face is the same at study and test but the right side of the face changes from study to test.

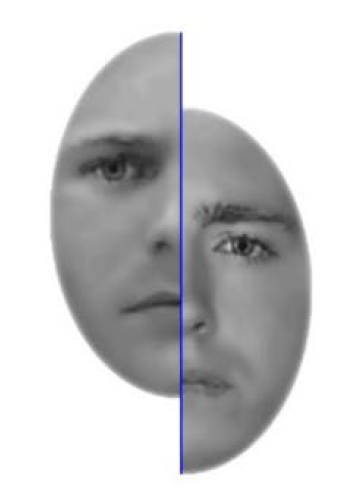

Second, the congruency effect is drastically reduced when the two parts of the face are misaligned – that is when the right part of the face is presented slightly lower than the left part (as in the image below), producing an alignment by congruency interaction.

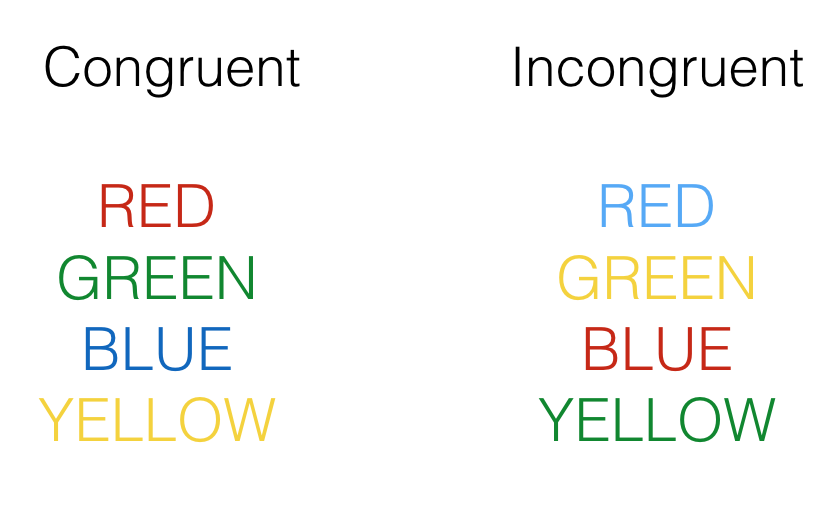

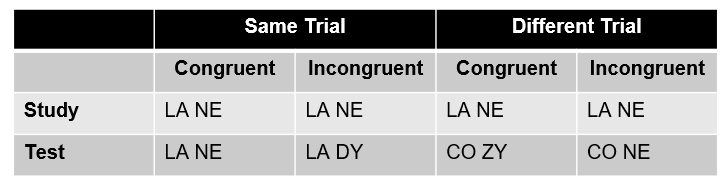

The congruency effect has also been found when words are used rather than faces (examples are in the table below), suggesting holistic processing of words as well. Does this mean that the mechanisms supporting holistic processing of faces and words are the same? Not necessarily, which is why the authors developed a modified composite task for their experiments.

Modified Composite Task

In the modified composite task, composite words were superimposed over composite faces – as in the figure below. Participants were then asked to ignore one stimulus (e.g., the words) while focusing on the other stimulus (e.g., the faces).

This task allowed the authors to investigate whether holistic processing of faces and words interfere with each other and thus share similar mechanisms. If so, the authors predicted that faces would be processed less holistically – as evidenced by a smaller congruency by alignment interaction – when superimposed with aligned rather than misaligned words (because aligned words are also processed holistically).

Ignore words, focus on faces

In the first experiment, undergraduate students from a university in Portugal underwent the modified composite task with instructions to focus on the faces and ignore the words. Participants completed 384 trials that all involved 4 phases: (1) fixation screen, (2) study stimulus (i.e., a face with a 4-letter word overlaid), (3) pattern mask, and (4) test stimulus (i.e., a face with a 4-letter word overlaid). Faces varied in whether they were congruent or incongruent, and aligned or misaligned. The superimposed words could also be aligned or misaligned.

Holistic word processing interferes with holistic face processing

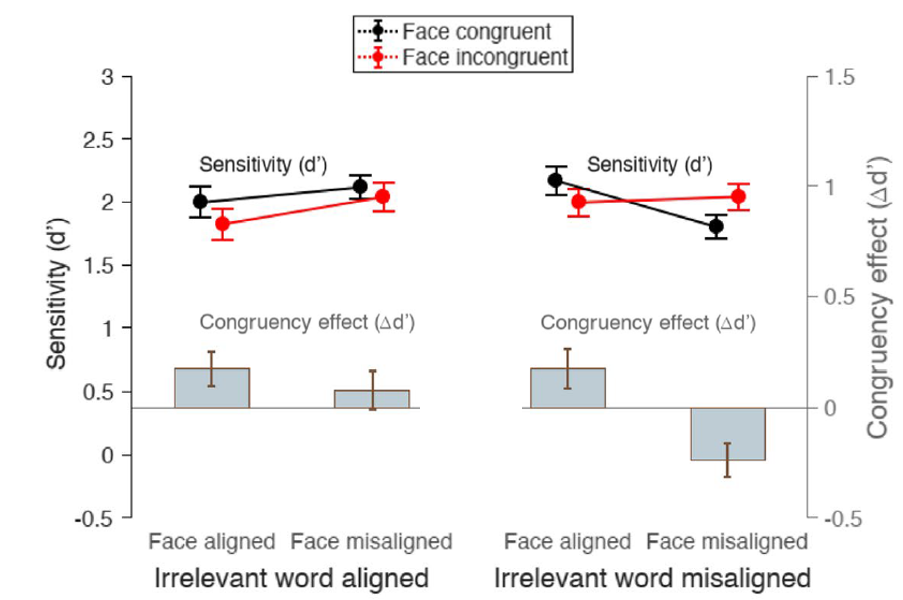

Consistent with the hypothesis that faces and words share mechanisms, the authors observed a significant three-way interaction between face congruency, face alignment, and word alignment on task performance (see figure below). Let’s break that down!

When the superimposed words were misaligned, an interaction was observed between face congruency and face alignment. Thus, holistic processing of faces was not impacted by irrelevant stimuli (words) when they were misaligned.

Critically, when the superimposed words were aligned, no such face congruency by face alignment interaction was observed!

Thus, whereas holistic face processing was found in the presence of misaligned words, no holistic face processing was found in the presence of aligned words – ultimately suggesting a specific interference with holistic face processing due to word alignment.

Putting it all together

Perceptual processing of faces and words is distinct, with dedicated regions in the brain. But Ventura and colleagues provide initial evidence that holistic processing of faces and words might share cognitive resources.

According to Ventura:

“These findings have important implications for our understanding of a hypothetical shared mechanism (i.e., shared cortical resources and cognitive processes) between face and word processing, and more broadly, the functional architecture of the mind.”

Featured Psychonomic Society article:

Ventura, P., Liu, T.T., Cruz, F., & Pereira, A. (2022). The mechanisms supporting holistic perception of words and faces are not independent. Memory & Cognition. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-022-01369-0