When was the last time you looked for a T among Ls?

Unless you spend a lot of time in the lab, running in visual search experiments, your experience of visual search probably isn’t looking for Ts amongst Ls. Your experience of visual search in day to day life is probably more like “where’s my phone?” or “where did my child lose their shoe?” – and if I’m looking for my phone, I should probably check under the cat first – visual search in the world can also be a huge part of your job.

Some of the classic examples here are radiologists looking at medical images, like mammograms, or security personnel looking at x-rays of bags. Those kinds of search tasks are really very different from Ts among Ls, and they’re different in a crucial way from the kinds of search that we engage in all the time (where did I leave my keys?).

There’s a huge amount of variability in the kinds of searches these experts do all the time – to say nothing of how weird an image looks! Imagine you’re a baggage screener, and you’re looking at a colourized X-ray image of someone’s bag – it’s a flattened, jumbled mess of shapes and colours, looking nothing like the bag would if you opened it up. How do these experts do this kind of search?

I’m all out of radiologists!

We can probably learn a lot about how these experts search for what they are looking for by studying them, but they are not easy to recruit. It is kind of a big ask to get radiologists to come to the lab (or even do an online study) in the middle of the day, when they have urgent scans to read for patients who need treatment. So, with this problem in mind, and a desire to learn about this particular corner of visual search, Michael Hout and colleagues (pictured below) asked themselves “can we build a stimulus set that lets us ask the same questions, but does not require us to find and persuade experts to participate in our studies?”

Making suitably odd stimuli

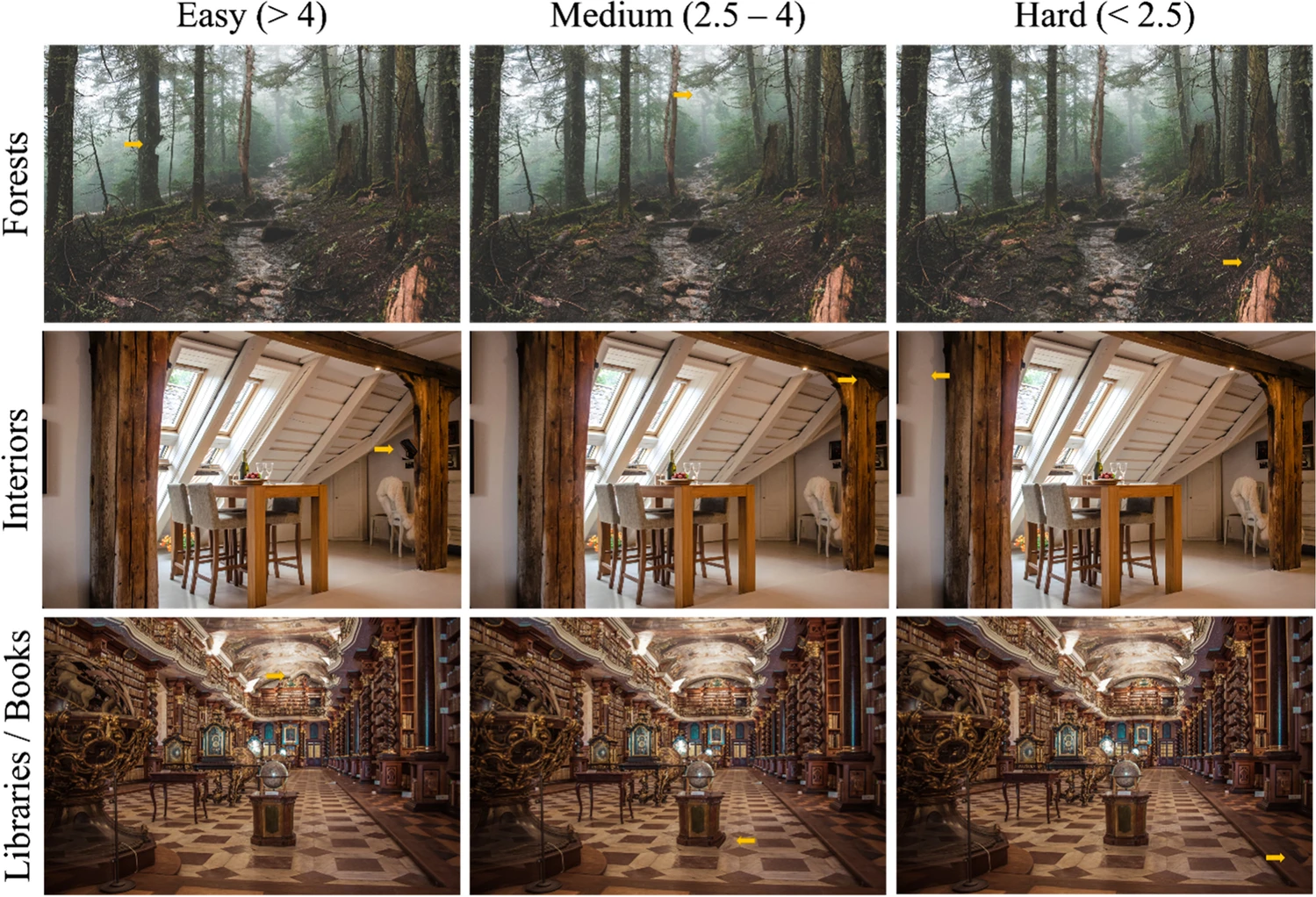

What really defines these sorts of search tasks is just how weird the search targets can be, and how jumbled the backgrounds can be – it’s not as simple as looking for a chicken amongst rabbits on a grey background! The thing is, most of us don’t have experience looking at X-rays of bags, or CT scans of body parts, but we all have experience looking at a huge range of natural scenes – in essence, we are experts and don’t even know it! So, Hout and colleagues used a range of natural scenes – indoor and outdoor scenes – and made a small portion of each one just a bit weird, distorting it in a way that people could find, if they were looking for it. Turns out, we’re pretty good at finding oddities like this, because the world isn’t usually distorted like this.

Is this search task hard in the right way, or is it just odd?

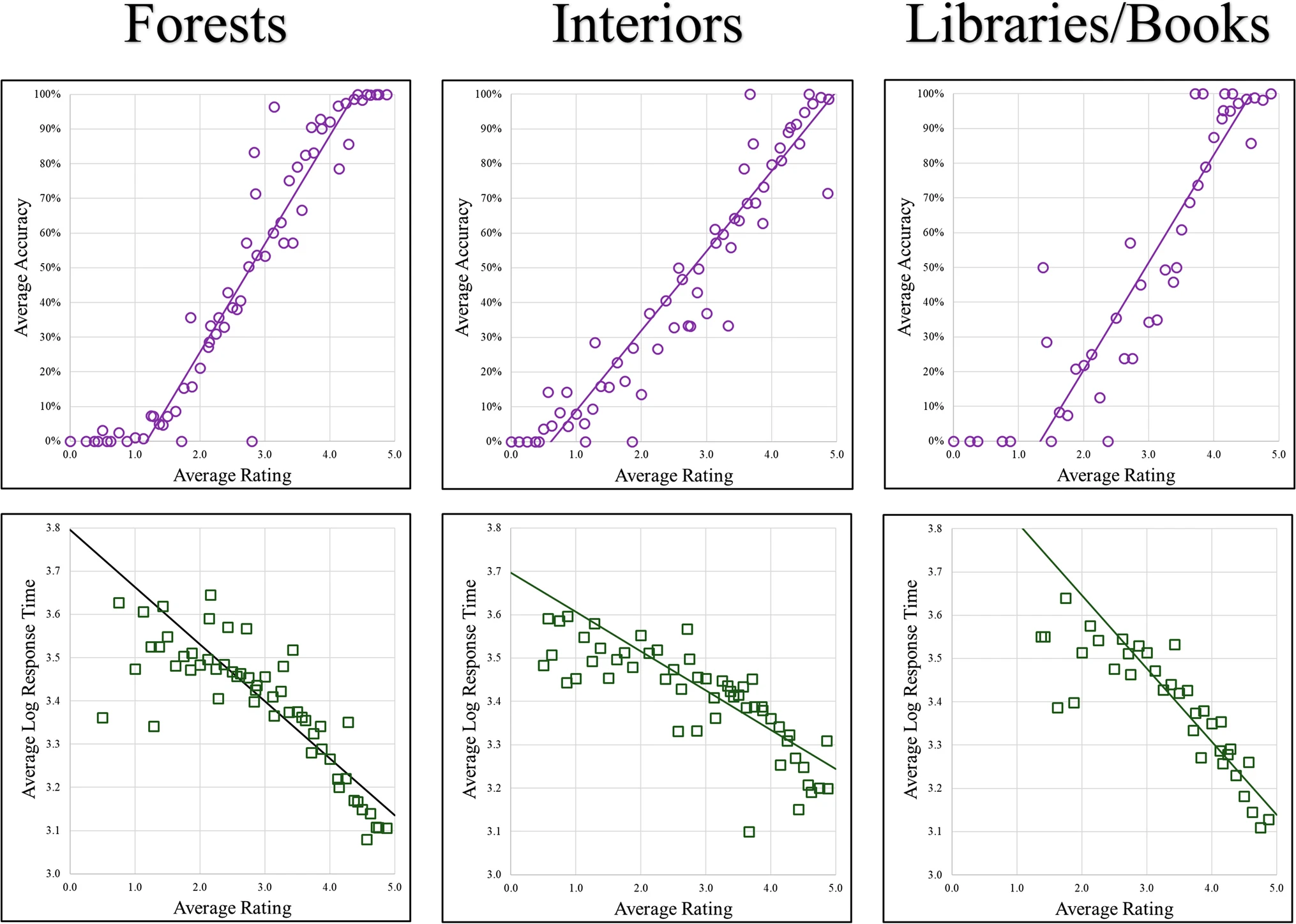

While building a new stimulus set is good, the key question for what Hout and colleagues needed to know was if they had built a stimulus set that would be useful for asking these sorts of real-world search questions without having to persuade experts into the lab. They rated the difficulty of the search task for each image and predicted search outcomes. To put this simply, if the team who built the stimulus set thought the search task, with an oddity in a given location, was easy, did other observers also have an easy time finding the oddity? That is, were they faster to find easy ones than hard ones? Fortunately, that’s exactly what Hout and colleagues found when they used their very odd stimuli in a search experiment!

What are the odds that the ODDS is useful for me?

So, if you’re interested in studying questions in visual search that look a lot more like our everyday experiences, or even that look like the special cases of search that radiologists and baggage screeners do all the time, the ODDS database might be just the tool you’re looking for. If you just want images of weird things, maybe it’s not the right tool for you, but if you want to know how people look for strange things in complex scenes, the odds are good that ODDS is what you might want. You can find it on the OSF – let’s all be a little odd!

Featured Psychonomic Society article

Hout, M.C., Papesh, M.H., Masadeh, S., Sandin, H., Walenchok, S.C., Post, P., Madrid, J., White, B., Pinto, J.D.G., Welsh, J. and Goode, D. (2022). The Oddity Detection in Diverse Scenes (ODDS) database: Validated real-world scenes for studying anomaly detection. Behavior Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01816-5