Warning: Some of the words in this post may be considered offensive.

One beauty of the English language is the seemingly infinite possibilities when it comes to making new words. People seem to get especially creative when they’re coming up with new phrases for insults and curse words—the type of language that tends to be taboo in polite company.

Take, for instance, one elected official’s Twitter declaration in February 2017, retweeted more than 13,000 times, in which he called another politician a “fascist, loofa-faced, shit-

gibbon.”

At the time of this post, the colorful term shitgibbon took Twitter by storm. Everyone wanted to know what a shitgibbon was, and it inspired people to offer additional compound

words as taboo insults (e.g., cockwomble, jizztrumpet, and fucknugget). I suppose some people bring out the best in all of us.

Furthermore, this tweet inspired Jaime Reilly and colleagues to ask the question: What makes a good bad word? They investigated this in a recent study that they published in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

Of course, the idea of combining two words to make a memorable obscenity is nothing new. Shakespeare had a propensity for coining clever new terms in his dialogue—such as flesh-monger (from Measure for Measure), lily-livered(from Macbeth), and puke-stocking (from Henry IV Part I)—but these words are not necessarily taboo. On the other hand, there are some compound words that sound offensive, but they are not intended to be—such as clatterfart (a person who gossips), kumbang (a hot, arid wind), and nicker-pecker (a European green woodpecker).

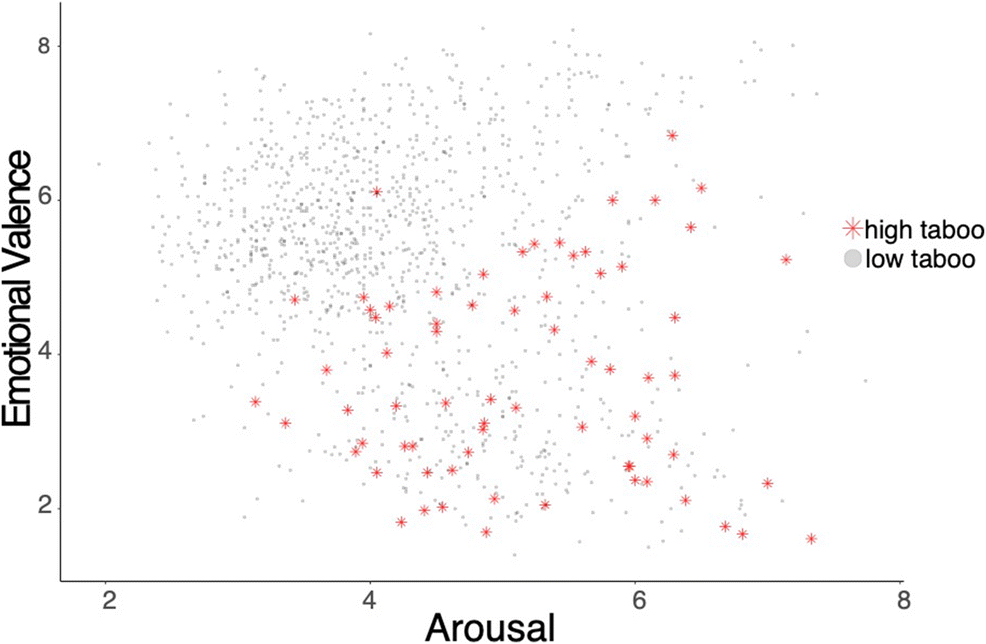

So what is it that makes a word particularly taboo? Janschewitz, in a 2008 paper published in a Psychonomic Society journal, Behavior Research Methods, proposed that tabooness is at the intersection of negative emotional valence and high physiological arousal, as displayed in the figure below.

In their recent publication, Reilly and colleagues suggested that there might be other factors that predict tabooness. To test this, they compiled a set of 23 psycholinguistic variables that could be potential predictors, as well as a corpus of 1,194 words. The word list included a combination of taboo and non-taboo entries. They recruited 190 participants via Mechanical Turk, and each rated approximately 500 words from the corpus using a 1-9 scale of tabooness.

Using these ratings, Reilly’s team found a linear model of predictive factors that accounted for 43% of the variance in tabooness. As predicted from the Janschewitz (2008) hypothesis, arousal and valence contributed the most to the model. They also found that words considered taboo were more often abstract rather than concrete, and these words often related to body parts, bodily acts, gender, and/or disease. Regarding word form, taboo words tended to have sharp consonants that abruptly cut off airflow (known as obstruents).

Reilly and colleagues took their investigation a step further by asking which common nouns would combine nicely with existing taboo words to create plausible new compounds. In this experiment, participants were given a common noun, and they rated it on a scale from 1 (very poor) to 7 (outstanding) for the potential to make a taboo compound. Words that already form taboo compounds—like hat, head, and hole—were removed from the list. Participants were encouraged to think of their own taboo word to make the compound and imagine it either before or after the common noun. For instance, if you see the word rocket, you could think of shit-rocket, rocket-shit, or whatever floats your boat. Then you would rate your newfound creation based on how acceptable it would be in the realm of profanity.

The results of this experiment were analyzed using a linear model that accounted for 24% of the variance in tabooness. The model revealed that participants preferred nouns that were shorter and had more stop consonants. Regarding semantic variables, words with emotional valence, physiological arousal, and reference to body parts, receptacles, animacy, and professions were judged to pair better in taboo compounds.

“The five strongest candidates for taboo compounding… included:

sack, trash, pig, rod, and mouth.

The five least acceptable candidates were

fireplace, restaurant, tennis, newspaper, and physician.”

These data show that taboo compounding is a legitimate process of word formation and not just random word combinations. This is important because it may guide treatment protocols for certain neurological disorders that involve uncontrolled taboo-word productions, such as severe expressive aphasia, Tourette Syndrome, and traumatic brain injury.

As shown in this study, the recipe for taboo words in American English typically includes the following ingredients:

- Physiological arousal

- Negative emotional valence

- Stop consonants

- Body relations, disease, or gender

With this list of ingredients, Reilly and colleagues posit that certain non-taboo words (such as welfare, abortion, and sodomy) have the potential to become taboo over time. I suppose it’s possible that we could also take a turn in the opposite direction and start using more non-taboo substitutions—like jeepers or fudge. The NBC sitcom The Good Place portrays an afterlife existence where curse words are spontaneously replaced with more respectful terms. But if this actually made a prominent impact on the English language, we would be royally forked.

Psychonomic Society article featured in this post:

Reilly, J., Kelly, A., Zuckerman, B. M., Twigg, P. P., Wells, M., Jobson, K. R., Flurie, M. (2020). Building the perfect curse word: A psycholinguistic investigation of the form and meaning of taboo words. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 27, 139-148. DOI: 10.3758/s13423-019-01685-8