While you might not think of it, your life and your experience of moving through the world is governed by innumerable sets of rules that you’ve learned. We tend not to think much about these rules or grammars, much less how we learn them, but they’re nearly as ubiquitous as the air we breathe.

Imagine picking up a new video game, and learning how to move your player through the game world – the game might give you a little bit of explicit instruction in the basic mechanics of movement (for a PC game, this might be the classic WASD keyboard mapping), but the game’s tutorial isn’t going to guide you through each and every possible action and consequence. At most, you’ll get a few brief training sessions, and then go on to play your game. If this is an experience you’ve had, you might not have thought about what it takes for you to become a skilled player, but a great deal of what you have to learn here comes down to inductively learning a chain of actions, since the game (or the world!) isn’t exactly going to walk you through everything that might or might not happen – you have to learn as you go.

While learning a video game might be an experience some of us are more familiar with than others, the larger question of what we can learn implicitly is an incredibly important question. When we think about how we learn, we tend to focus on explicit learning and consciously accessible knowledge, but the vast majority of what we know about the world – the knowledge and skills that let us function in the world – are implicit, and rarely impinge on our consciousness. This is, frankly, a good thing – when was the last time you consciously had to think about the act of walking? To better understand implicit learning, Răzvan Jurchiș and Zoltan Dienes (pictured below) asked whether we can learn sequence grammars from more natural stimuli, since those are what the world, of course, asks us to learn. Authors of the featured article, Răzvan Jurchiș (left) and Zoltan Dienes (right).

Authors of the featured article, Răzvan Jurchiș (left) and Zoltan Dienes (right).

What’s meant by a grammar?

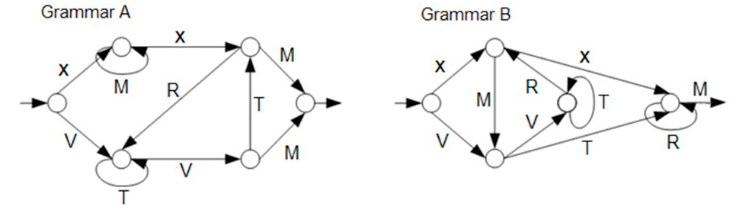

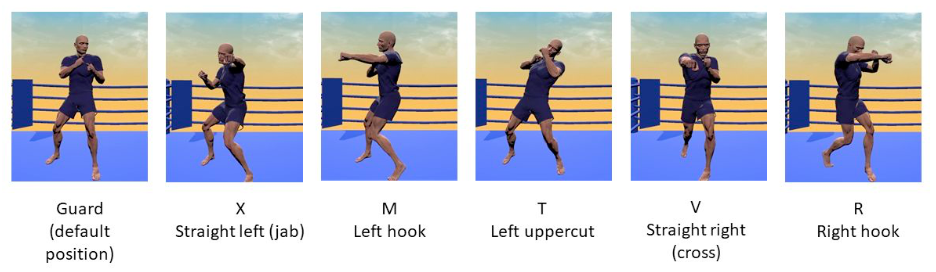

You might be used to thinking of grammar as something exclusively in the domain of language, but the larger idea of a grammar as a set of rules that constrain how we do something, whether it’s speaking or pouring a cup of coffee, pervade our lives. While it’s possible to learn a grammar – linguistic or otherwise – in an explicit fashion, it’s not something we do that much. To test whether we can learn these sorts of rules in a more naturalistic fashion, Jurchiș and Dienes adapted a common technique from studies of implicit learning – the Artificial Grammar Learning task (shown in the image below) – and translated it to boxing motions in VR (see image below).

The Artificial Grammar Learning (AGL) task is a very abstract way to study our ability to learn rules and detect violations, usually tested by asking participants to memorize strings of letters and reporting whether those strings include grammatical violations. In their study, Jurchiș and Dienes transformed these strings into sequences of boxing moves made by a virtual boxer, bringing the AGL much closer to the kinds of sequences we might learn in the world rather than in the laboratory.

Is it really implicit?

The key question in Jurchiș and Dienes’ work isn’t whether we can learn these sorts of predictions, but whether we do so without conscious awareness. Their results suggest that we very much can learn these grammars implicitly. You might imagine, having learned such a grammar, that you’d be able to articulate the rules of the grammar explicitly, but in much the same way that you probably can’t articulate each and every grammatical rule for English, Jurchiș and Dienes’ participants knew when a sequence was right or wrong, even if they couldn’t necessarily articulate why. Our lives are pervaded by this kind of implicit knowledge and implicit learning – we acquire some knowledge explicitly, but we pick up far more without actively seeking to learn it because our existence in the world demands that we do.

What does this mean for me?

Jurchiș and Dienes’ paper gives us an intriguing window into a usually-closed part of how we learn about the world – while implicit learning is undoubtedly a huge part of how we develop the skills to move through and interact with the world, its very nature makes it hard to study. Moving towards stimuli that look more like the world we inhabit – like their boxer stimuli – helps us understand how we learn implicitly when we’re outside the laboratory. While you might not need to learn a sequence of boxing moves, the rules of how we move our bodies and the sequences in which we do so – the grammar – is something we have all been learning since birth.

Featured Psychonomic Society article

Jurchiș, R., & Dienes, Z. (2022). Implicit learning of regularities followed by realistic body movements in virtual reality. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-022-02175-0