Memory is such a fickle thing. Have you ever found yourself forgetting things that you should have remembered and remembered things that you should have forgotten? This happens to me all the time! I can completely forget where I placed my cell phone, even if placed minutes ago. However, I can remember lyrics to a song I haven’t heard in years, maybe even decades (ahem…do not try to do the math!).

What’s more is, even if I can recall a thing (like an item from a list I need to purchase from the store), that does not necessarily mean I will be able to recognize that exact thing from a written list given to me. Sounds nutty, right? This phenomenon is known as “recognition failure for recallable words.” Memory researchers have found that during a cued-recall test (where participants are shown one word from a studied pair of words and are asked to recall or recognize the other word pair), participants can reliably generate words from memory (i.e., recall), but not identify those very same words from a list (i.e., recognize).

The reverse can also happen. If I am able to recognize an item from a presented list (or at least part of the item), there is no guarantee that I will also be able to recall it.

So why might I not be able to recognize something I just recalled? And what are the cognitive processes in the brain that underlie the recognition failure for recallable words phenomenon? These are the very questions Ozubko, Sirianni, Ahmad, MacLeod, and Addante (pictured below) examined in a recent paper published in the Psychonomic Society journal, Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience.

They explored whether recognition failure occurs because of:

- the way recall is probed. It may make a difference if participants are given a cue during recall or if they must try to generate responses without a cue). Or,

- the task demand. Participants might wonder why they are being asked to recognize a word they just produced and might behave in an artificial way. That is, they may overproduce words during recall, knowing they can reject them later, and they may reject words because they feel obligated to during recognition.

To test this, in Experiment 1, participants studied 24 target words and later asked them to recall those words. The manipulation occurred during recall. One group of participants was given a word cue (the cued-recall condition), and the other group did not receive a cue (the free recall condition). In the cued-recall condition, the word cues were either semantically related to the target word (e.g., PRINCESS as a cue for KING) or unrelated (e.g., GALAXY as a cue for KING) to the target.

After each time participants recalled a word, they then saw that exact word in the middle of the screen and were asked to judge whether it was old (i.e., presented on the study list) or if it was new (i.e., not presented during study). Experiment 2 used a similar study design as Experiment 1, except the recognition question (the old/new judgment) was omitted.

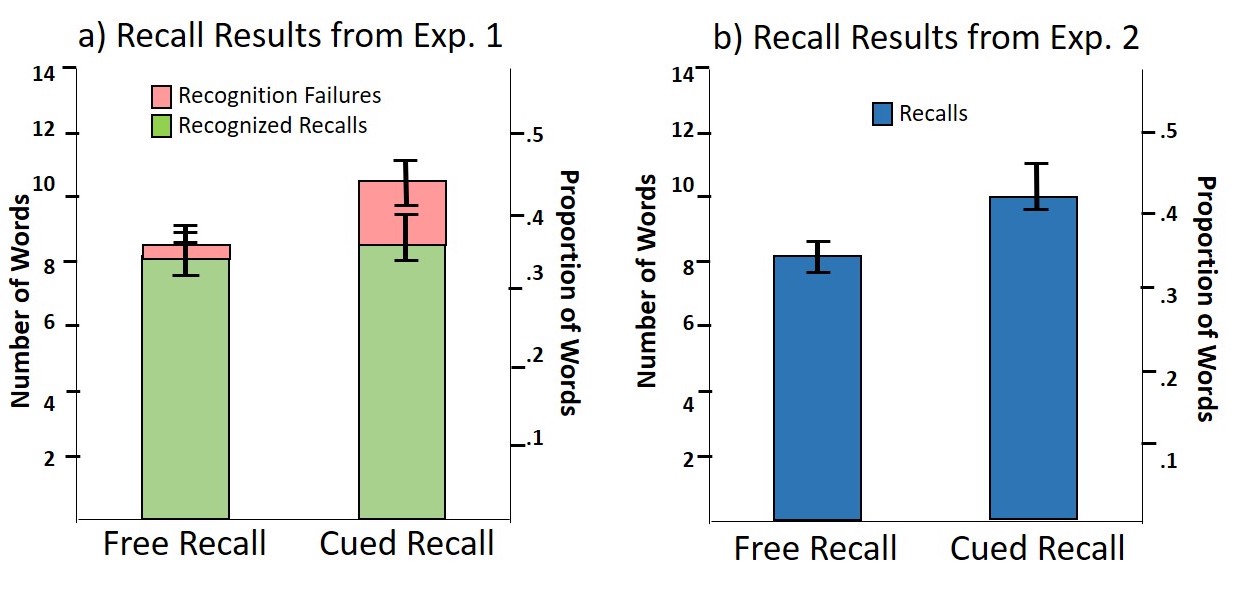

The results were quite interesting, as shown in the figure below. First, there were significantly more recognition failures in the cued-recall condition than in the free-recall condition. Also, there was no difference in either the number of recalled words in the cued-recall conditions between Experiment 1 and Experiment 2, or in the free-recall conditions.

Taken together, the results suggest that recognition failures are a product of having cues present during recall and are likely to be present even if an explicit recognition decision is not required.

The researchers also used electrophysiological methods to understand whether recall responses and recognition failures fundamentally differ at the electrophysiological level (the figure below shows a participant engaged in the task). In two experiments measuring event-related potentials (ERPs) and memory simultaneously (using a task similar to Experiment 1 and 2), they found distinct neural signatures for recognized recalls and recognition failures. Recognized recall items were likely to be driven by neural processes associated with recollection and familiarity, while recognition failures are likely to be driven by processes associated with implicit semantic priming.

There are instances where although we can recall a thing, we might not be able to recognize it immediately after. And whether or not a semantic cue is presented plays a prominent role. This research takes us another step toward better understanding the fickle nature of memory.

Featured Psychonomic Society article:

Ozubko, J.D., Sirianni, L.A., Ahmad, F.N., MacLeod, C.M., & Addante, R. J. (2021). Recallable but not recognizable: The influence of semantic priming in recall paradigms. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 21, 119-143. DOI.10.3758/s13415-020-00854-w.