Psychological research could play a critical role in informing policies during times of crisis and uncertainty. However, as stated in a previous post by Patrick Forscher, Simine Vazire, and Farid Anvari during this digital event, issues with generalisability, replicability, and validity may limit the practical implications of our research.

The problems of reliability are compounded by the fact that in times of crisis, the rapid dissemination of evidence is as critical as its quality. Thus, the field finds itself in a challenging situation, where the need for quality and rapid knowledge challenges the utility of psychology research. As Ulrike Hahn put it in a previous post during this digital event; there is a need for proper science without the drag.

But researchers have not sat idle.

On the contrary, some have started building an infrastructure for crisis knowledge management, described in the earlier post by Stefan Herzog. Others have started posting their findings as “living documents”, as described by Yasmina Okan in her post. And many more have published their findings as preprints as soon as they emerge, without the “drag” introduced by peer review.

Preprints offer the opportunity to “speed up”’ the production of (ultimately) peer-reviewed studies by increasing access for the wider community. Across disciplines, the availability of preprints has increased in line with the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the clinical repository medRxiv posts 50-100 daily COVID-19 related preprints. At their best, preprints can enhance communication between academics, many of whom vigorously discuss preprints on Twitter and other social media, and thus allow for a broader range of feedback than is possible through conventional peer review, which is not only slow but limited to a small number of reviewers.

Preprints may therefore aid in facilitating rapid and valid knowledge in the context of COVID-19—maybe they are the new “science without the drag” that we are seeking?

The jury on this is still out, and we cannot adjudicate this possibility here.

Nonetheless, the rapid production of COVID-19 preprints warrants an investigation into the utility, development, and reach of these preprints. The psychological preprint repository PsyArXiv experiences a constant flow of COVID-19 related psychological research, but what happens next with these papers? What disciplines of psychology are being investigated? What is the reach of these preprints via social media and through downloads?

We sought answers to those questions by analyzing 217 PsyArXiv preprints that were posted on COVID-19 before 2020-05-13

Metadata such as preprint URL, study title, corresponding authors, disciplines, tags, upload date, disciplines, tags, google scholar citations, and tweets were collected for each preprint. The disciplines metadata allows the author to describe which psychological subfields the preprint belongs to. The disciplines metadata allows the author to categorize the preprint into subfields of psychology (for example health psychology). A tag allows the author to describe the content of the preprint (e.g., mental health could be a common tag in a clinical psychology preprint).

We contacted corresponding authors informally by email to track the progress of the preprints to date. The authors told us whether they have had any reviewer comments, submitted to journals, and they also provided information about their previous work, and their overall experiences in conducting the research. We then conducted correlational analysis between metadata, used text analysis to interpret author experiences, created twitter preprint citation networks, and word clouds to determine common themes in disciplines, tags, and titles Here we report 4 results, mainly focusing on the metadata.

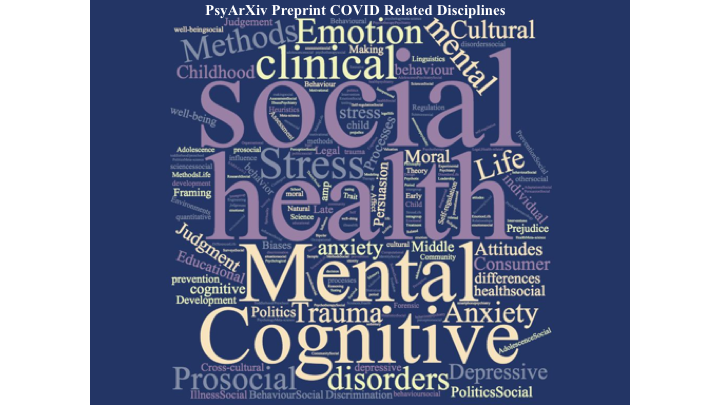

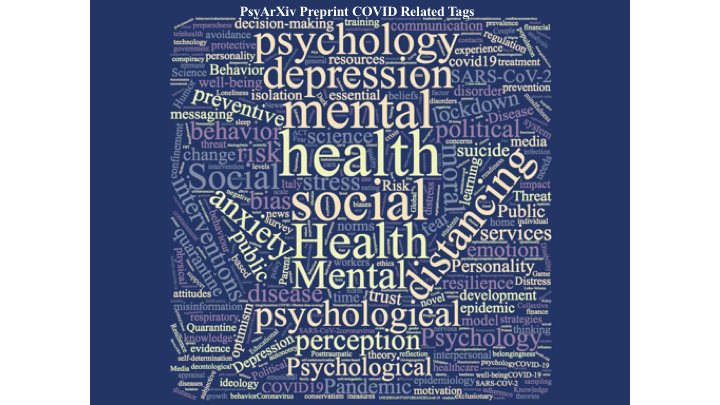

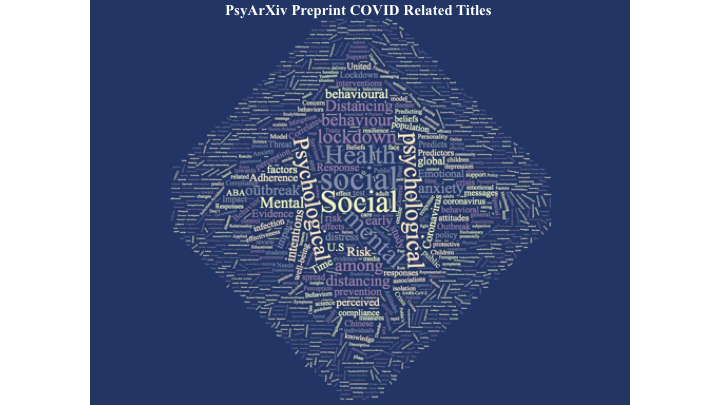

Word cloud

The process of analysing word clouds, although a simple analysis, can draw out some useful information when looking for overarching themes in a dataset. We ran separate word clouds for titles, disciplines, and tags. The word clouds presented below indicated that across the set of metadata, mental health-related terms appeared to predominate. Particularly in the disciplines and tags clouds, words such as trauma, emotion, and depression pop up regularly.

The word cloud below shows the common disciplines attached to the COVID-19 PsyArXiv preprints.

The word cloud below shows the common tags submitted to the COVID-19 related PsyArXiv preprints.

The word cloud below shows the common words found in COVID-19 related PsyArXiv preprint titles.

It appears that COVID-19 related preprints on PsyArXiv have a leaning towards the production of clinical and health-related psychology papers. Funders and scholars can harvest this information and, where necessary, create a better balance in the field of knowledge. For example, COVID related psychology research could focus some efforts into other streams such as misinformation, occupational psychology, and personality.

What do the authors say

Communicating with the corresponding authors provided insight into the development of the preprints. Out of 68 authors who replied to our email, 42 said they had not received reviewer comments, whereas 26 said that they had. 62 out of 68 authors indicated that they had submitted the paper for publication, and 59 reported that they were continuing to work on the topic. It appears that preprints are almost universally a stepping stone towards publication.

Preprint metrics

For each preprint, we recorded the total number of downloads, as well as citations on Google Scholar and mentions on Twitter. Mentions on Twitter were counted manually by entering each preprint URL into the Twitter search tab.

We analyzed the metrics in three ways: First, we classified preprints according to whether or not they had received reviewer comments. As shown below, there was little difference between preprints that received reviewer comments and those that did not in terms of the mean number of citations, tweets, and downloads.

| Reviewer Comments |

Mean Downloads |

Mean Twitter Mentions | Mean Google Scholar Citations |

| No |

493.76 95% CI [230.7012, 756.8188] |

4.62

95% CI [2.4425, 6.7975] |

1.13 95% CI [0.0987, 2.1613] |

|

Yes |

464.68

95% CI [142.7075, 786.6525] |

4.55

95% CI [1.794, 7.306] |

1.06 95% CI [-0.2354, 2.3554] |

There was little difference in elapsed time since being posted between preprints that had received reviewer comments (Mean = 30.16, SD = 14.30) and those that had not received reviewer comments (Mean = 31.26, SD = 14.93).

We then correlated the metrics with each other, as shown in the table below. Unsurprisingly, downloads correlated with citations and tweets, as well as elapsed time—that is, the time since a preprint was posted.

|

downloads |

GS citations |

tweets | |

| GS citations |

0.86 |

1.00 |

0.57 |

|

tweets |

0.58 |

0.57 |

1.00 |

|

elapsed time |

0.51 |

0.43 |

0.27 |

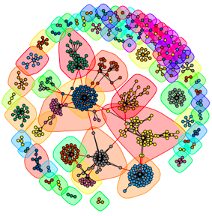

Retweet and Mentions Networks

We collected tweets that either contained the title or URL of a preprint by connecting to the Twitter REST API with the rtweet package. After removing duplicate messages (tweets with identical message text and posting account), this left 634 tweets about the preprints for analysis that were posted between 11 and 19 May 2020. It should be noted, however, that the tweets analyzed here represent only a fraction of the discussion taking place on Twitter. Not only does the standard Twitter API restrict data collection to a ten-day period from the time of searching, but by using full preprint titles and URLs as search terms, we neglect messages where individuals do not refer to a preprint by its full title and messages where the URL has taken a shortened format (e.g., “t.co/” instead of “psyarxiv.com/”).

We then plotted a graph of the preprint sharing network such that links between nodes indicate a retweet, mention, or reply. The resulting network consisted of 580 nodes (i.e., Twitter accounts), with a median degree (i.e., number of links per node) of 2 and a maximum of 114 (SD = 8.97).

Finally, we applied the walktrap community detection algorithm, which identified 93 communities (modularity = 0.88). A community is defined as a sub-network of nodes that are highly related to each other, which in this context simply refers to Twitter accounts that retweeted or mentioned the same preprints. Modularity values describe the segregation between communities and lie in the range 0 to 1. A value M < .4 hints at a low separation among communities, between M = .4 and M = .6 indicates a medium separation between communities, and M ≥ .6 implies a high distinctiveness of the communities. While the walktrap algorithm assumes that each node can only belong to a single community, which is often not the case in real-world social networks, the high modularity suggests the algorithm is an appropriate fit for the data analyzed here. In other words, the high modularity seems to indicate a high distinctiveness between communities, with few bridges being made between conversations and groups. This was also observed by noting that only 27 nodes (4.6% of the Twitter accounts) have greater than zero betweenness centrality.

The graph is visualized in the figure below, using color to identify communities.

Summary

Our brief analysis suggests that mental health-related studies have a significant presence in the overall number of PsyArXiv preprints. Although this stream of research is critical, it may also point to gaps in the current understanding of the psychological consequences of COVID-19.

There are encouraging signs that preprints are helping to facilitate the rapid and valid production of knowledge. Most preprints were submitted for publication, thus indicating a move towards publication.

These findings are far from conclusive, but they are consonant with the idea that preprints are facilitating a shift towards proper science without the drag.

CrediT author statement: Contributors

We are using the new CrediT scheme to acknowledge authors and contributors

Muhsin Yesilada* (University of Bristol) Conceptualization (input on study design), contributed to data curation, project administration, contributed to data analysis, contributed to methodology, contributed to visualisation, contributed to writing [original draft and/or review & editing]

Stephan Lewandowsky (University of Bristol) Conceptualization (input on study design), contributed to methodology, editing of draft posts

Ulrike Hahn (Birkbeck College, University of London) Conceptualization (project idea, input on study design), contributed to data analysis, contributed to methodology, contributed to visualisation, reviewing of draft posts

Stefan M. Herzog (Max Planck Institute for Human Development) Conceptualization (input on study design)

Jason William Burton (Birkbeck College, University of London) Data analysis and visualisation of preprint sharing network on Twitter

Marlene Wulf (Max Planck Institute for Human Development) Recruitment and supervision of volunteers

Erik Stuchly (University of Bristol) Contribution to data curation

Siyan Ye (University of Bristol) Contribution to data curation

Gaurav Saxena (University of Bristol) Contribution to data curation

Gail El-Halaby (University of Bristol) Contribution to data curation