I have played sports my whole life—swimming, tennis, basketball, track, cycling, fencing, soccer—you name it, I have probably tried it. Even though I loved working hard and competing, I still remember boys snidely remarking, “Girls can’t play sports” or “You run like such a girl!” I tried not to listen, but I would be lying if I said it didn’t make me a little self-conscious. I wasn’t able to compete as well when they were watching either—I didn’t want to prove them right. Luckily, for sports like fencing, where I could compete against boys, beating them handily usually made me feel better.

In situations where people are afraid that their performance could reinforce a negative stereotype, especially when around other people, they often perform worse than they might otherwise. This unfortunate, self-fulfilling prophecy is called stereotype threat. The ramifications of being threatened by harmful stereotypes extend far beyond sports and into cognitive science, potentially throwing into doubt long-held assumptions about the mind.

One of the most widespread stereotypes about the mind is that the older we get, the worse our memory becomes. While the occasional memory error can be funny—it’s hard not to giggle when someone needs help finding the glasses currently perched on their own head—this stereotype can carry darker implications for how older adults see themselves and their own capabilities.

To dig into the potential cognitive consequences of this stereotype, a recent study published in Memory & Cognition by Marie Mazerolle, Lucas Rotolo, and François Maquestiaux (pictured below) tested whether older adults’ poor performance on a classic memory task might actually be due to stereotype threat. Their results are sobering: if experimenters purposefully try to reduce the presence of the “older adults have bad memory” stereotype, older adults do much better on the memory task. In some conditions, older adults performed just as well as younger adults.

“This [finding] challenges traditional beliefs about age-related memory decline,” the authors said.

They tested a specific type of memory called associative memory. Think of this type of memory as the ability to remember which things belong together. For example, my associative memory allows me to remember (without peeking) that my lunch today consists of oatmeal, dried cranberries, and an orange. These single items are linked together by virtue of them being my lunch, and I am able to recall them as a collection.

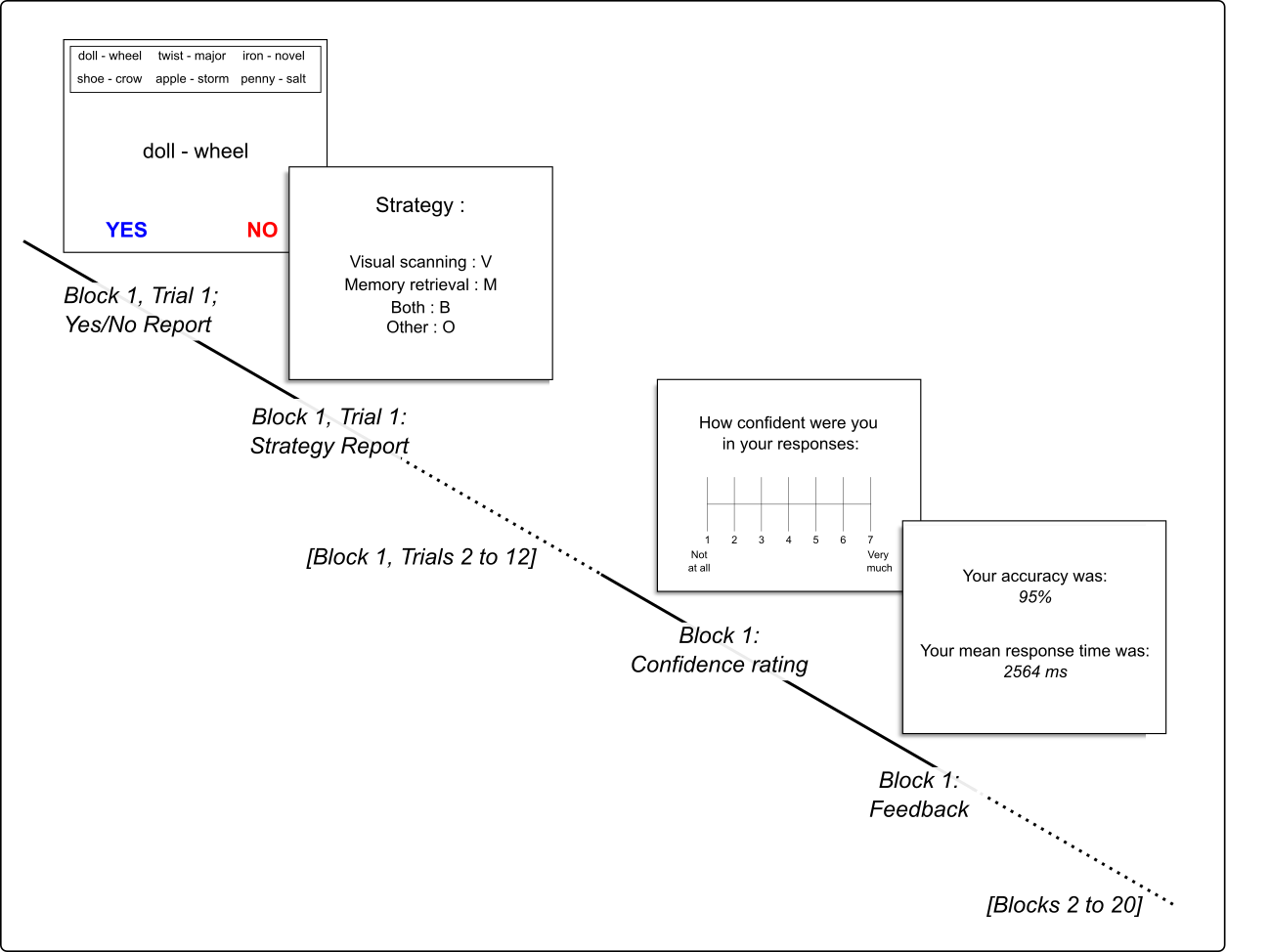

Forty older (ages 59-88) and forty younger (ages 17-27) adults took part in the study. For the task (shown below), participants decided whether or not a pair of nouns presented on the screen (e.g., doll – wheel) matched one of the six noun-pairs listed along the top of the screen.

Typically, participants chose one of two strategies to do the task well. The safer strategy is to visually scan the list of noun-pairs at the top for the target. While this strategy is usually highly accurate, it’s also quite slow. The faster strategy is to memorize all of the listed noun-pairs so that when a new target appears, the participant can quickly tell, via memory retrieval, if the target pair matches any on the list.

Critically, experimenters manipulated the presence of stereotype threat for the older and younger adults taking part in the study. The older adults in the high-threat condition had their age prominently displayed on the screen and were told that younger adults were also taking part in the study, giving the declining memory stereotype the limelight. The stereotype activated for younger adults involved intellectual achievement and comparison with other students.

The authors hypothesized that inducing the stereotype threat would cause older adults to default to the more conservative visual scan strategy instead of the faster memory retrieval strategy to avoid “proving” that their memory was in decline.

In the low-threat condition, everyone was told that older and younger adults were participating but that the experimenters did not usually see an age difference in the task. In sum, the high-threat condition was designed to bring stereotypes about aging and intellectual performance to the forefront of participants’ minds, while the low-threat condition made the task feel more like a leisurely walk in the park.

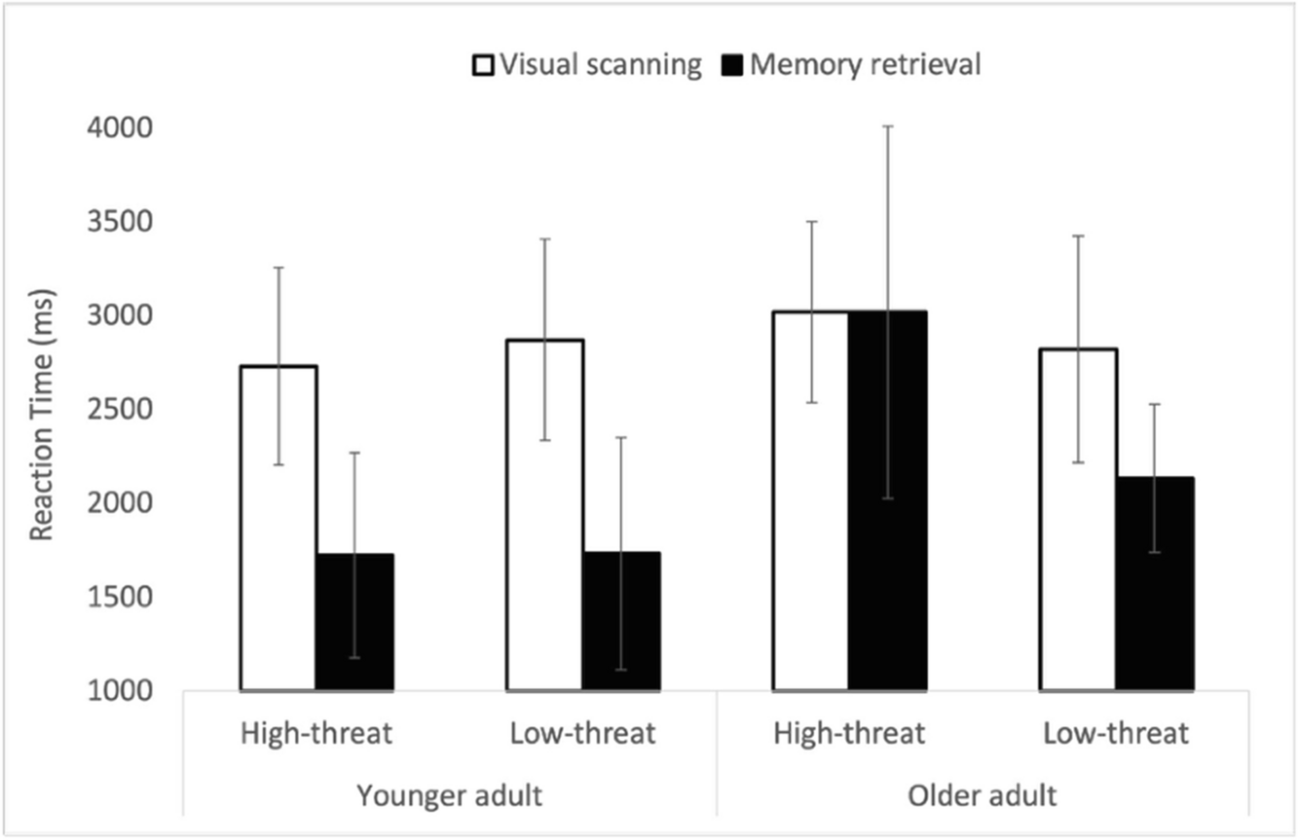

The results were startling but promising for older adults. The older adults in the low-threat condition did not perform significantly differently than the younger adults in the low-threat condition. In other words, when age-pertinent stereotypes were opposed by the experimenters, older adults did just as well on the memory task as the younger adults.

This contrasts starkly with the results in the high-threat condition: older adults were an average of 832 ms slower than the younger adults, replicating the classic finding that older adults perform worse on this memory task. Interestingly, older adults also reported using the memory retrieval strategy less often in the high-threat condition, suggesting that stereotype threat might have influenced how they chose to approach the task (see graph below), lending support to the authors’ hypothesis.

The authors remarked on the consequences of this finding,

“…urging a reevaluation of testing conditions to minimize stereotype threat and better understand the true potential of older adults’ memory capacity.”

So, where does this leave us? At the very least, we should be more mindful of how we interact with our participants can, sometimes dramatically, affect how they perform. These results also bear on our lives outside of the lab—like my experience playing sports. To combat stereotype threat, we can all work harder to keep our words kind, respectful, and stereotype-free. So, please, let’s drop comments like “throws like a girl.”

Featured Psychonomic Society article

Mazerolle, M., Rotolo, L., & Maquestiaux, F. (2023). Overcoming age differences in memory retrieval by reducing stereotype threat. Memory & Cognition. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-023-01488-2