Given all that has been recently written about the current state of psychology and the challenges that we face as a field, I am happy to say that the 50th anniversary of the Atkinson-Shiffrin model and the special issue in Memory and Cognition celebrating it couldn’t have been timelier. Although highly cited (over 10,000 times, according to Google Scholar), my feeling is that Atkinson and Shiffrin’s chapter is woefully underread, with most people encountering the work in it through secondary sources. This situation is unfortunate for many reasons. One of them is that it is harder to appreciate its enduring influence in a lot of research conducted these days. Despite their breadth, the papers included in the special issue provide only a snapshot.

Another reason – in my view more important – for reading the work of Atkinson and Shiffrin is that it features many notions regarding theory development that should be more prevalent in psychological science at large. Also interesting is the fact that some of the features popularized today as necessary for the `salvation’ of psychological science, such as pre-registration, are clearly absent. As I will argue below, these features turn out to be pretty much redundant in a theory-centered research program like Atkinson and Shiffrin’s.

Putting Theory and Effects in Their Place

In a tour de force spanning over 100 pages, Atkinson and Shiffrin propose a theoretical framework for human memory. The first 30-odd pages of the chapter are dedicated to describing the two types of processes that are going to be considered and the different ways in which they can interact: On one hand, we have structural processes corresponding to permanent features of the memory system. Among these are the sensory register and the short-term and long-term memory stores. On the other hand, we have control processes, which are differentially applied to the structural processes at the convenience of the subjects. Examples of controlled processes include strategies regarding the allocation of attention to different stimuli; the way information is searched in the different memory stores, and so on. Notable among these is a rehearsal buffer in the short-term store that allows for information to be preserved either via rehearsal or through a transfer to the long-term store. Later on, the focus is shifted to a long series of experiments (eight are highlighted) designed to showcase how control is exercised, along with the fits of models satisfying the principles laid out by the theoretical framework.

Right at the forefront, we are given a proposal for a mechanistic explanation of mnemonic capacities: How exactly can people learn/remember things, and how can they do so in an active manner. The key here is the fact that the processes proposed are general enough that they transcend any specific ‘effect’, and that the discussion of the latter is completely subservient to the former. In other words, effects are only interesting to the extent that they can be used to put different explanations to the test.

Interestingly, this stance by Atkinson and Shiffrin anticipates subsequent philosophical work on the nature of explanation in psychological science. Echoing an earlier piece by Iris van Rooij discussing this work, I find it unfortunate that a disproportionate amount of researchers’ efforts are currently being placed on the study of the reliability of effects rather than on the development of plausible explanations of human capacities and understanding how they can be empirically assessed. After all, a poor understanding of how theory relates with data can have drastic consequences and lead researchers astray for decades, even if the effects being studied are robust. A recent paper by Caren Rotello and colleagues published in Psychonomic Bulletin and Review discusses several examples.

For instance, in a research program like the one developed by Atkinson and Shiffrin, pre-registration efforts are of little use because pre-registration is, in a sense, already implied by the relationship between theory and data (whether the researcher is aware of this or not; see the recent posts by Danielle Navarro and Iris van Rooij in the Psychonomic Society’s previous digital event on preregistration).

Take the case of the list-strength effect: According to a large class of global matching models, the memory-judgment accuracy for a given set of studied items should be dependent on the memory strength of other studied items. But as shown by Ratcliff, Shiffrin and colleagues, such an effect is found in the case of free-recall tasks but turns out to be absent in the case of recognition memory. This null result rejects the class of global matching models. At the end of the day, it is irrelevant whether the effect was predicted beforehand or discovered by accident. What matters is that the effect is at odds with an entire class of global matching models.

Theories, Models, and Their Evaluation

Another important feature in Atkinson and Shiffrin is how the theoretical and empirical sections are linked. Specifically, we see a clear distinction between the theoretical framework and the different models that can be constructed based on it. The models fulfill the ideas found in the theory (e.g., there are different memory stores; a buffer), but also include a series of auxiliary assumptions (e.g., items are transferred from the buffer at a constant rate) that help us to implement the different processes assumed to be operating in a given task. Auxiliary assumptions are always necessary because data are always insufficient to determine all parts of a theory. Various justifications can be used in the selection of these auxiliary assumptions, such as their tractability or flexibility. In some cases, the choices made might be completely arbitrary (see Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968, p. 171).

The presence of auxiliary assumptions means that one needs to be very careful when assessing the relative success of a model. After all, they might be behind a model’s failure to account for some data. Because of this possibility, researchers should be careful when determining which criteria to use in the evaluation of models. In some cases, a model’s ability to provide a minute description of some data might not be as important as just being able to capture a general pattern of findings. In other cases, it might be reasonable to expect models to produce more fine-grained accounts. Atkinson and Shiffrin’s discussions of model fits reflect these concerns, and in many cases they only focus on the models’ ability to capture the gist of the data. Some of the challenges and dynamics present in model development, such as the tinkering with different auxiliary assumptions, and evaluation of model performance under multiple criteria are discussed in detail in a great piece by Shiffrin and Nobel.

Attitudes towards model fits has somewhat shifted since then, with many people now focusing on some model-performance statistic that (in some specific way) takes into account the finer details of each model and their contrast with the data. But as discussed by Danielle Navarro, this new attitude comes with considerable risks, given that it can distract researchers from the main patterns of results in the data.

The Challenge of Modeling Control

Separating the contribution of the structural and control processes in a given task is far from trivial. One major challenge is the complexity of the notion of control, which includes many types of behaviors, from attempts to overcome or suppress some process to the adoption of a specific strategy that only happens to be adaptive in a given environment. One way to overcome the complexity or multiplicity of control processes is to take a piecemeal approach in which we determine how control is likely to be exercised in a particular task, given the task characteristics and the participants’ goals and expectations. Atkinson and Shiffrin adopted such an approach: Instead of trying to explicitly model control processes in a general manner, they developed different models across tasks, each reflecting the specific ways in which they expected control to be exercised.

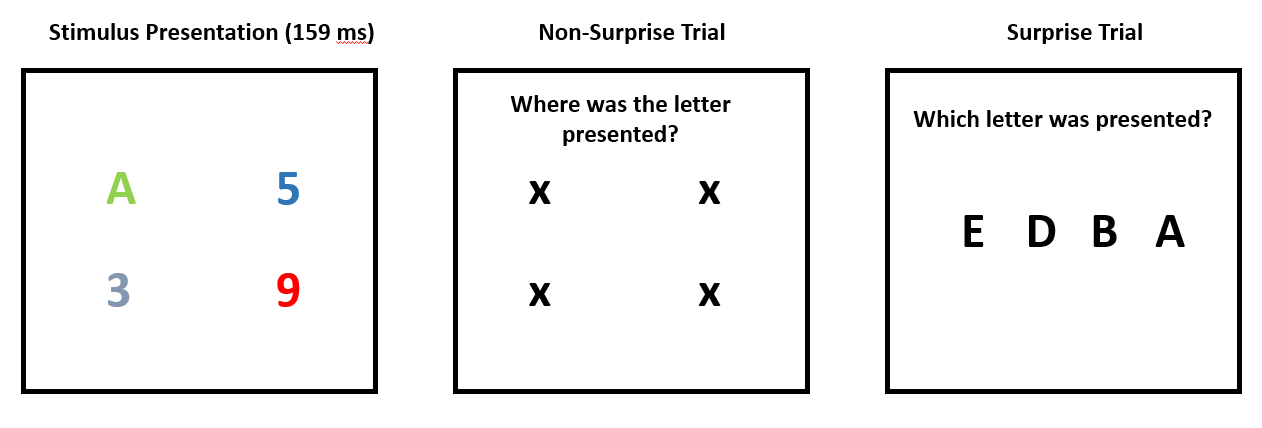

This brings me to one of the papers in the special issue, entitled “Learning how to exploit sources of information” by Brad Wyble and colleagues. This paper focuses on the way individuals’ expectations regarding a visual working-memory task modulates the type of mnemonic information available to them at the time of judgment. Wyble and colleagues argue that feature information that is integral to the stimulus, but not relevant for the task at hand, should become less available than it could otherwise be. This unavailability should increase as participants become more accustomed to the task. The figure below illustrates the stimuli used in their task.

Each trial of the first experimental task used involved the brief presentation of four stimuli, 3 numbers and 1 letter (see the leftmost panel in the above figure). After this brief presentation, participants were asked to indicate the position (but not identity) of the letter stimulus on the screen among four alternatives. After a number of non-surprise trials (ranging from 0 to 49), participants were given a surprise trial in which they were instead asked to indicate the identity of the letter stimulus among four possible alternatives. Results showed a clear decrease in accuracy on surprise trials as a function of its delay: When the surprise trial was the first one, participants identified the correct letter with 60% accuracy (chance level is 25%). By contrast, when the surprise occurred on the 50th trial, accuracy was only 30%. Accuracy in the non-surprise trials prior to the surprise was generally stable (around 80%).

The results from this study highlight a very important issue. The way participants engage with tasks is closely tied to the characteristics of the experimental design, likely in ways that are overlooked by researchers. This raises the possibility that our understanding of the underlying mechanisms might be severely biased by the distribution of experimental designs that we usually adopt. If that is the case, then the more similar to each other our experimental designs become, the greater this bias should be. Also, results would appear to be more consistent, giving us a false sense of confidence.

Final Thoughts

Although the chapter by Atkinson and Shiffrin is half a century old, it continues to inspire a large body of progressive research programs that are likely to continue prospering in the foreseeable future. However, it is too often celebrated from afar, with people missing out on some of its qualities. Today is a perfect day to (re)read it, maybe together with other classics: The original 1967 technical report (no. 110) is freely available in the archive of the Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences. The archive is a goldmine for classic articles in early cognitive science.

Psychonomics article being highlighted:

Wyble, B., Hess, M., O’Donnell, R.E. Chen, H., & Eitam, B. (2018). Learning how to exploit sources of information. Memory & Cognition. DOI: 10.3758/s13421-018-0881-x.