Atkinson and Shiffrin’s seminal 1968 paper is best known for outlining a possible structure for the memory system. Their concepts of sensory memory, short-term memory and long-term memory are still highly influential. Often forgotten, however, is that Atkinson and Shiffrin also described multiple control processes that determine how and if information moves through the memory system. That is, whether information will be remembered or forgotten. These control processes include regulating attention to determine what moves from sensory memory to short-term memory, rehearsing information to maintain it in short-term memory, and the processes used to search through long-term memory, among others. In fact, all memory strategies can be considered types of control processes within the Atkinson and Shiffrin model.

Today, I want to talk about a specific control process not mentioned in their paper – the ability to determine when information is presented and for how long. This level of control is rare in many naturalistic situations. One cannot control the timing and length of a sunset in order to ensure that it will be remembered. However, this level of control is common when people are intentionally trying to remember information. A student who is trying to learn new vocabulary terms will often use flashcards to study for an upcoming test. The student is in control both of how long she spends studying each word and definition, but also when the next flashcard is displayed. Does this level of control improve memory? That is the question tackled by Patel, Steyvers and Benjamin in this special issue.

First, let’s discuss controlling the amount of time spent studying each item. There are a number of reasons why having this level of control might be valuable. Some information is inherently more difficult to remember than others and people may benefit by spending additional study time on difficult items. In addition, our attention fluctuates over time and it may be useful to wait out lapses of attention. For example, if it is optimal to study each item for two seconds, but you catch yourself mind wandering 1 second into a trial, you’ll now want to study that item for 3 seconds.

Research suggests that this level of control is helpful. Learners remember more information when they are able to control how long they study each item. Furthermore, this finding has been replicated numerous times – occurring with words, word pairs, and faces. In a typical study, one set of participants is asked to study a list of items and they are able to control how long they study each item (self-paced group). A second set of participants has no control and is paired with a participant in the self-paced group. These participants either study each item for exactly as long as their paired participant or for the average study time for that participant. The results consistently show an advantage for the self-paced group.

In the current article, Patel and colleagues examine if controlling when information appears has similar advantages. Controlling when an item appears may help memory by allowing learners to continue rehearsing an earlier item until they are ready to move on. Alternatively, learners whose attention has wandered may postpone the next item until they are focused and ready to continue. Yet, across four experiments, the authors find no evidence that controlling when a to-be-remembered item appears improves memory.

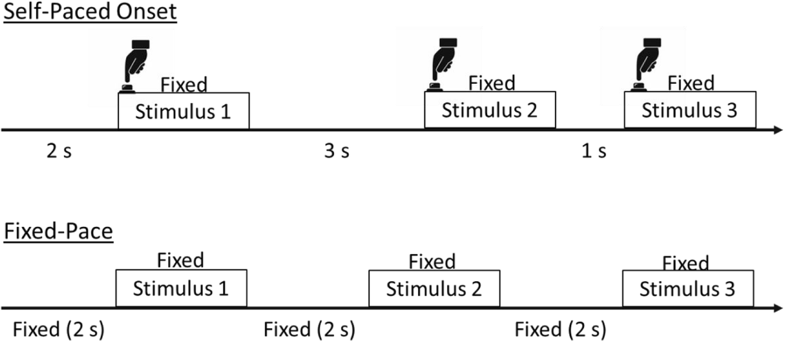

Experiment 2 illustrates this finding clearly. Participants were workers from Amazon Mechanical Turk who were asked to try to remember a list of eighty words for a later test. During this study phase, one group was able to control when each item was presented (self-paced onset) while participants in the control group had no control over the presentation of the items (fixed-pace). As shown below, each participant in the fixed-pace group was paired with a participant in the self-paced group. That is, the gap between items for them was equivalent to the average gap for their paired participant.

Participants were then given an immediate recognition test where they saw 160 words and had to decide for each test word whether it was one that they had previously studied or a new word. Participants in both groups were equally accurate in distinguishing the new and old words. Controlling when the items were presented did not improve learners’ memory for the items.

Similar results were found in Experiment 1 when the gap between words in the fixed-pace condition was set by the experimenters rather than by a previous participant, in Experiment 3 with undergraduate students as the participants, and in Experiment 4 where the to-be-remembered items were faces rather than words.

Determining when the next item should appear did not improve memory.

This stands in stark contrast to the reliable benefits that occur when learners are able to self-pace how long they study each item.

So why does controlling when an item is presented not benefit memory? There are three main possibilities. First, people may be able to fully sustain attention during the short (5-10 min) study phase. Thus, there are no fluctuations in attention for them to notice and no need to alter their pacing of the material. However, speaking against that possibility, in a recent study using a task of similar length, researchers found that learners’ attention did fluctuate across items and that participants had better memory for items that were presented while they were fully attending to the task.

Second, people may not be able to monitor and notice the small lapses of attention that occur during the task. While their attention levels are fluctuating, people may not be able to recognize when they are and are not paying attention. In support, research on mind wandering suggests that people often fail to notice when their minds have wandered.

Finally, even if people do notice the variation in their attention level, they may not use that signal to decide when to proceed to the next item. The research on effective learning is full of situations where learners do not realize what’s best for improving their memory and thus, they do not utilize the most effective study strategies. Perhaps learners are aware that their attention level varies, but do not realize that it would be more effective to wait until they are fully attentive before presenting the next item. If this is the case, then explicit instructions on when and how to decide to present the next item would be beneficial.

So, let’s go back to the student studying for a vocabulary test. Is it okay if they automatize the presentation of their flashcards on the computer or should they manually control the timing? The current results suggest that it’s important for the student to control how long they study each item, but it does not matter if they have control over when the next item is presented. Control is useful, but only in some situations.

Featured Psychonomic Society article:

Patel, T. N., Steyvers, M., & Benjamin, A. S. (2019). Monitoring the ebb and flow of attention: Does controlling the onset of stimuli during encoding enhance memory? Memory & Cognition, 1-13. DOI: 0.3758/s13421-019-00899-4.