Have you ever found yourself whispering something to yourself in the comfort of your own head? If you had, you’re not alone. Many people – but not all – do. This phenomenon is known as internal verbalization or inner speech.

Curiously, people who don’t experience internal verbalization are surprised about the notion of others “listening” to an inner monologue because this rarely or never happens to them. At the same time, people who usually experience internal verbalization are puzzled when discovering that there are people who don’t. This has led to engaging viral Twitter threads that prompted a re-discovery of existing research on internal verbalization.

As you can imagine, there’s a myriad of possibilities between the extremes of never listening to your “mind’s voice” to doing it constantly. There’s also a broad spectrum of variations in how people speak to themselves. Some tend to do it using full phrases, others telegraphically. Some tend to scold and criticize themselves, while others engage in more optimistic forms of self-talk.

Nevertheless, understanding how all the phenomenological characteristics of inner speech impact behavior and other psychological processes is no easy task. As is always the case in psychological research, you must be able to measure a phenomenon – and do so validly and reliably – if you are interested in relating it with behavioral and psychological outcomes.

But how to measure something seemingly as fleeting and immaterial as internal verbalization? This is the topic that Hettie Roebuck and Gary Lupyan (pictured below) address in their paper “The Internal Representations Questionnaire: Measuring modes of thinking,” published in Behavior Research Methods.

Measuring inner speech

Roebuck and Lupyan designed the Internal Representation Questionnaire (IRQ) to measure individual differences in internal verbalization and the impact on other psychological processes. The IRQ was primarily conceived to provide a reliable measure of “people’s propensity to use internalized language in different situations that do not involve communication with other people,” such as in situations involving memory retrieval, imagery, and problem-solving.

They also wanted to design an instrument that assessed other phenomenological experiences associated with internal representations, such as visual, auditory, and tactile imagery. To do so, they incorporated items from other previously validated instruments. Measuring different types of internal representations on the same instrument allows for comparisons.

After following a standard process for designing psychometric scales, including steps such as factor analyses, test-retest reliability tests, and probing the instrument’s internal and external validity, four factors retained:

- Internal Verbalization: Includes items related to experiencing thoughts using internal verbalization, such as “I think about problems in my mind in the form of a conversation with myself.”

- Visual Imagery: Includes items describing aspects of visual/pictorial imagery, such as “I can close my eyes and easily picture a scene that I have experienced.”

- Orthographic Imagery: Includes items related to visualizing language as it is written, such as “When I hear someone talking, I see words written down in my mind.”

- Representational Manipulation: This factor clusters items related to different sensory modalities. The common theme was related to manipulating mental representations. Examples are: “I can easily imagine and mentally rotate three-dimensional geometric figures,” “It is easy for me to imagine the sensation of licking a brick,” and “I can easily imagine the sound of a trumpet getting louder.”

From inner speech to observable behavior

A key interest of the authors leading this research is understanding “how differences in phenomenology relate to differences in behavior.” Accordingly, the authors wanted to go beyond the more psychometrically oriented tests conducted in the construction and validation phase of the instrument.

To do so, they designed a predictive validity test. Specifically, the authors explored whether people’s IRQ profiles can predict performance on a speeded word-picture verification task. In this task, participants must indicate as fast as possible whether a cue – for example, the image of a dog – matches an upcoming target – for example, the word “dog.” By comparing the speed in matching targets to cues, they can measure whether the different IRQ factors relate to task performance.

As the main interest was testing the relationship between internal verbalization and task performance, the authors compared individuals scoring high (above 75%) or low (below 25%) in the Internal Verbalization measure of the IRQ. They hypothesized that people with higher internal verbalization scores would:

- Activate phonological representations from pictures faster or to a higher degree. This should be reflected in shorter reaction times (RTs) in trials where the cue (picture) and target (word) match.

- Show a higher degree of phonological interference. This should be reflected in slower RTs in rejecting a picture (e.g., an image of a foot) after a word that sounded similar to its name (e.g., “root”).

- Show less semantic interference. This should be reflected in semantically related cue-target pairs (e.g., a pair of “shoe” and a “toe”), slowing their RTs to a lesser extent.

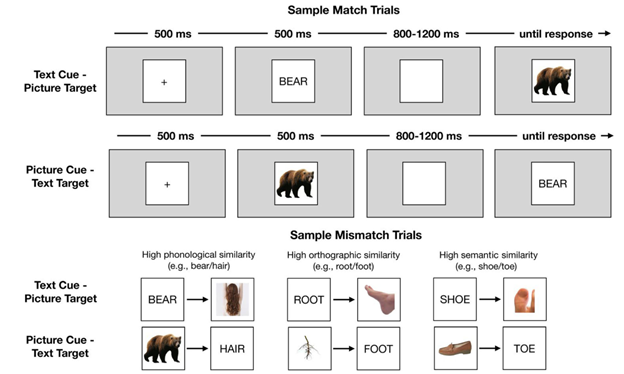

As the upper part of the figure below shows, in each trial, a cue was presented (a written word or a picture) followed by a target of the opposite type. The participants should respond as fast as possible whether the cue and target matched or not.

In addition, for mismatching trials, the target could have a phonological similarity (e.g., hair, which sounds like bear), orthographic similarity (e.g., root, which is written similar to foot), or semantic similarity (e.g., shoe and toe, which are part of the same semantic field).

Some predictions were confirmed. People with higher internal verbalization scores showed:

- slower RTs when the word cue and the picture target were phonologically similar, revealing increased phonological interference

- reduced semantic interference, but this effect was only observed in the context of text-picture trials

The expected effect of shorter RTs in matching trials due to enhanced phonological representations was not found. Instead, a surprising finding was that higher internal verbalization was associated with slower RT when the cue was a picture. A possible interpretation is that people with higher internal verbalization scores are less efficient at using pictorial cues because (unlike the written cues) they don’t automatically provide a context that allows activating phonetic representations.

The data allowed the authors to provide evidence on how individual differences in the phenomenology of internal representations can relate to specific behavioral outcomes. From their perspective, it is important to test the relationship between the propensity to internally verbalize with performance in other tasks.

According to the authors,

It is possible that people whose thinking feels to them as more language-like may show more categorical processing on a variety of domains such as reasoning, mental imagery, and patterns of errors in recall.

Indeed, these are intriguing possibilities, and addressing them is much easier as the groundwork of test development has been made. The IRQ can be a valuable tool for researchers interested in the relationships between the phenomenology internal representations and a variety of complex behavioral outcomes.

Featured Psychonomic Society article

Roebuck, H., & Lupyan, G. The Internal Representations Questionnaire: Measuring modes of thinking. Behavior Research Methods 52, 2053–2070 https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01354-y