How am I supposed to learn my way around this confusing new place?

Picture the following situation: you’re on vacation, you’ve spent all day (and then some) in airports and on planes, and you’ve finally made it to your hotel. Now you’ve got to find your room, and you need to remember how to get from the lobby up to your room. Many hotels are pretty blandly designed, and your travel-zombie state isn’t helping. The member of staff who gave you your room key gave you directions – they said it’s a left then a right to get to the elevator, then take the elevator up to the 12th floor, and then you should take a right at the painting of the moose, then a left, then a right, and then follow signs to your room. This is the kind of situation we all find ourselves in pretty regularly, whether we’re on vacation or wishing we were – you’ve gone to a new big-box store, and you’re trying to learn where things are, or you’re teaching a class in a new room and you have to learn how to get there from your office.

Real-life wayfinding: Have you felt lost in an endless hotel maze, stumbling along and wondering whether the designer wanted you to feel lost, rather than relaxed?

Rather than just finding this sort of everyday task a source of frustration, Otmar Bock, Ju-Yi Huang, Özgür A. Onur, and Daniel Memmert (pictured below) were interested in how they could use a similar task to understand how we learn to do these sorts of route-following tasks, and what information we rely on.

How do we do this?

There are a few possibilities here – maybe we just memorize the route itself, and provided we can hold on to that sequence, that’s all we need. If that was the case, all we might need to know would be “left, right, left, left, right, etc.” and we might be completely oblivious to everything else in our environment, because it wouldn’t be relevant to our ability to find our way. Alternatively, we might rely on visual landmarks, or cues in the visual environment, to guide ourselves – “oh, I can see the two meter sculpture of a chicken, I need to turn left here” – that sculpture might be memorable, but it could be a lot of detail to remember, and many environments we navigate aren’t that distinct.

Pretty memorable but do you remember where to turn now that you’ve seen the chicken?

How might we use this information?

With these two overall strategies in mind, the authors put forward three hypotheses of how their participants might complete a route-following task in the laboratory. One possibility was the winner prevails strategy, where participants would either use serial order, memorizing the route sequence, or cue association, remembering what was where, based on whichever of the two helped them make their way along the route. Another possibility they articulated was the strategy enhancement approach, where participants might mostly use serial order, but use specific remembered cues to break up a long sequence of directions into smaller, easier to remember, sequences. One last possibility was a dual strategy tactic, where participants might use both sequence memorization and visual landmarks to help guide themselves through the task.

Taking this question into the lab

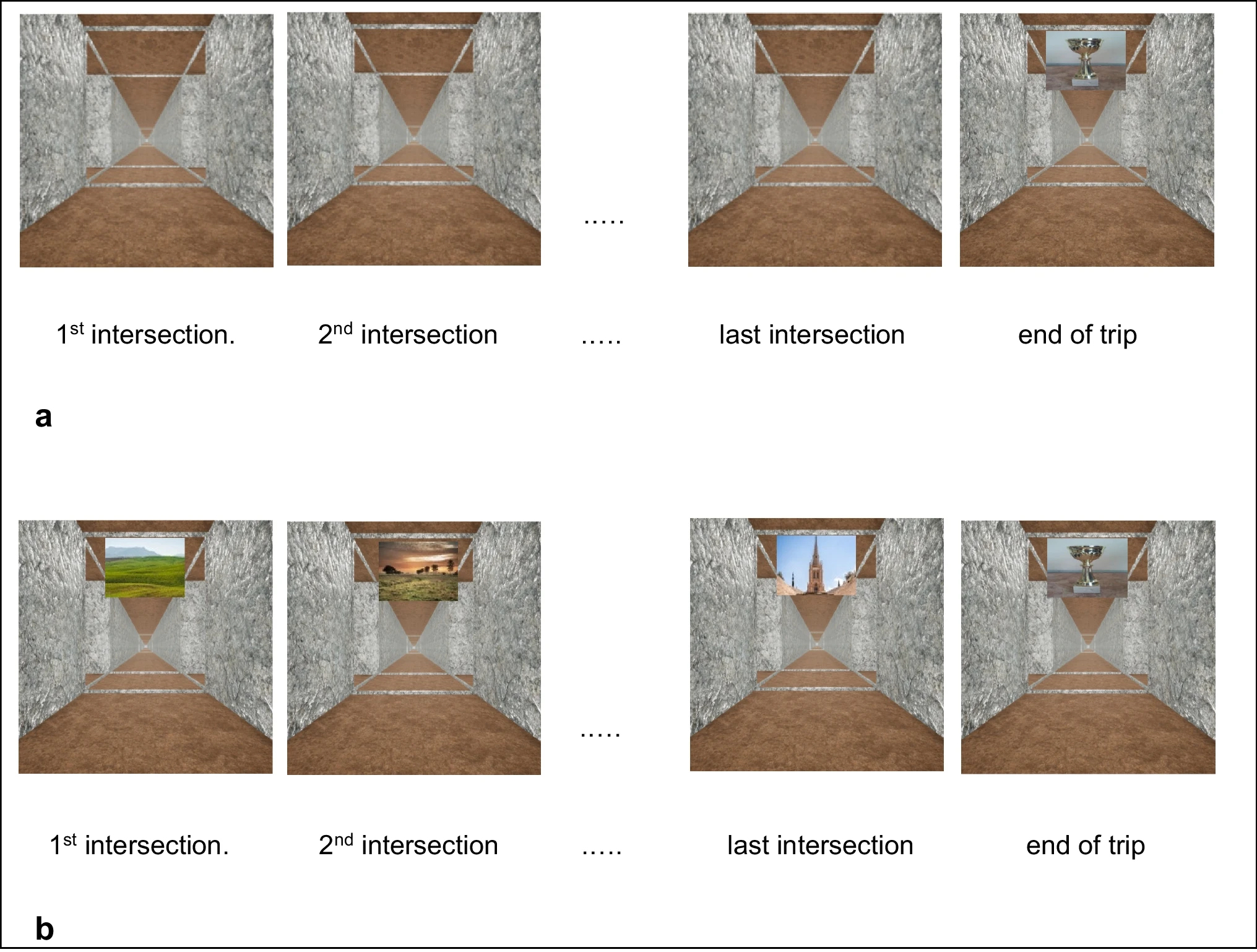

Since teasing these three possibilities – and two strategies – apart is tricky if they had just let their participants wander a confusing hotel (or university building), Bock and colleagues brought this route-following task into the lab and had their participants navigate a virtual maze. In some of these mazes, there wasn’t any visual information at a given intersection to help guide them – forcing them to rely on their recollection of the sequence. In others, the intersections themselves helped guide participants where to go – think of wandering your vacation hotel and seeing a directional arrow and a sign saying “Rooms 1231-1248.” The key condition in their study provided both forms of information, but didn’t let participants exclusively rely on one or the other, and even in long sequences – up to nearly twenty intersections – participants were able to use both their knowledge of the route sequence and their recollection of landmarks to help guide them better than either type of information alone.

Two strategies, together

Thinking about these sorts of tasks – which we do all the time – Bock and colleagues’ findings suggest that it’s probably better to not rely on either the serial order or environmental cue strategy exclusively. If you think about what it’s like to find your way in a new environment, that makes a lot of sense, since relying on a perfectly memorized sequence could be very brittle, and if you don’t remember whether you’re at the 10th or 12th intersection, you could get very lost – and similarly, if you remember that you needed to turn at the Starbucks, it doesn’t help much if there’s one on every block! So, like with so many things, having multiple strategies is the best approach, even if it seems like a lot to remember.

Featured Psychonomic Society article

Bock, O., Huang, JY., Onur, Ö.A., Memmert, D. (2023). Choice between decision-making strategies in human route-following. Memory & Cognition, https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-023-01422-6