Those who can, do; those who can’t, play video games?

Video games offer an alternative, simplified, gamified reality. Players can compete imbued with athletic prowess, military skills and tools, and superhuman abilities of all sorts, regardless of real world limitations. But some video games offer simulations that are remarkably life-like. Do players of those games benefit by developing real world skills?

Racecar drivers are now honing their talent with racing video games, and NFL football players play football games, which some say help them on the field. Music video games, like Guitar Hero or Rock Band, provide players the opportunity to play simplified versions of drums, bass, guitar, and vocals along with a wide variety of famous hits from pop and rock music. But, do players of music video games actually have musical aptitude, similar to real musicians?

A recent article in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review addressed this question.

In the game Guitar Hero, players attempt to match the tempo and basic melody of a song (say, Bohemian Rhapsody) using a guitar-shaped controller (pictured below). Players must “strum” the white string-like button, while pressing a combination of the colored buttons, as colored circles stream past to the beat of the song. The better their execution, the better their score, and the better the song sounds. When players miss a note by hitting the wrong color or strumming at the wrong time, an out-of-tune misstep embarrassingly plays. Rock Band features other instruments (bass, drums, and vocals) as well. Clearly, these games share some similarities with playing actual instruments. Timing, finger placement, melody understanding, and anticipation all must be mastered by both the guitarist and the guitar hero.

The influence of video game play on cognition is becoming very well-studied, and has been discussed on this blog before. While there is some debate, there are many studies showing that video game play is associated with cognitive benefits. Playing Tetris improves mental rotation ability, and playing action video games improves cognitive and perceptual performance, across a number of measures.

Researchers Pasinski, Hannon, and Snyder therefore had good reason to predict that playing music video games might support skills involved in music aptitude, but this had never been directly tested. To test this question, the researchers first administered a large screening survey, in which participants were asked about, among other things, their video game and music playing habits. They selected participants to one of three groups. Music video game players had to be able to play Guitar Hero or Rock Band on Expert – no small feat. Musicians had to have formal musical training for at least 6 years, and had to have played within the last 5 years. A third group of control participants were eligible if they had no music video game or musical experience (at least formally).

Participants were brought into the lab and completed three tasks. First, they all played Rock Band. Second, they completed a set of musical aptitude measures called the Profile of Music Perception Skills (PROMS – try it yourself! I am somewhat musical and scored a 26.5). PROMS consists of several measures of musical ability – how well can you remember the precise tempo, melody, tonal structure, and rhythm of a piece of music. Finally, participants completed the big five inventory personality measure.

Intriguingly, music video game players matched musicians on all four subtasks of the PROMS, showing they had equal musical aptitude after no experience with real musical instruments (data pictured below). Both groups outperformed control participants who had comparatively worse performance on all subtasks except rhythm.

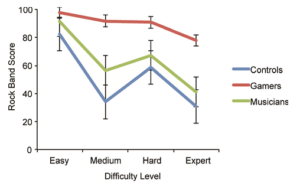

So musical video game players could perceive musical differences as easily as musicians, but perhaps musicians would be equally competent with music video games. Instead, perhaps surprisingly, the musicians performed similarly to the control group on Rock Band, scoring far worse than the music video game group (data pictured below). This could simply be explained by the musicians’ lack of practice with Rock Band, specifically. It also reveals that musical aptitude itself is not enough to excel at a musical video game. Gamers would have had practice with the specific songs and patterns they played, as well as the somewhat idiosyncratic controls.

The study by Pasinski and colleagues reveals that music video game players have equivalent musical aptitude to trained musicians. Of course, as the authors admit, there are limitations to these findings. Perhaps music video game players and musicians both share a love of music, and might listen to more music, attend to it more closely, and be more discriminating than the comparably less-musical control group. Perhaps both groups already have an aptitude for music when they learn an instrument or pick up Guitar Hero, and their skill encourages them to stick with it, while less musical players may drop out.

One factor the authors do rule out is general personality differences – the groups showed no differences on the Big Five personality measures. Future studies, Pasinski and colleagues point out, should investigate the role of music video games with a training paradigm, to see whether they might play a causal role in the deveopment of musical aptitude.

Nevertheless, the results of this study promote cautious optimism. Studies have shown that musical ability promotes and requires a large set of cognitive skills (one such study was discussed on this blog previously). The authors point out that formal music training may be prohibitively expensive or time-consuming for some socioeconomic groups, a hurdle which is less steep for video games.

As yet, there is no word on whether air guitar, another cheap substitute for the real thing, promotes musical training. Although, it’s clearly just as cool, especially if you are the world champion:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RnK702CeqO4]

This research also opens the door for similar studies in other domains, with the potential for educational or remedial impact. Virtual reality applications have been developed to train surgeons, and to help older adults re-gain balance. As the video game world more closely mirrors, emulates, and infringes on reality, these benefits may become even greater, but studying how these benefits are similar to those attained from real world practice is an important research question.

Reference for the article discussed in this post:

Pasinski, A. C., Hannon, E. E., & Snyder, J. S. (2016). How musical are music video game players? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. DOI: 10.3758/s13423-015-0998-x.

1 Comment