Picture this time of the year: exam weeks. Students are spending day and night in the library, going through their summaries over and over again, highlighting the most important parts of their notes in various colors, re-watching lectures, and just trying to cram as much as possible before the exam. With little time for good food or sports, students come out of these exam weeks exhausted, but happily enter their vacation. Then, coming back to university after summer, most of what they have learned seems to be forgotten. Because most of them passed their exams, it is back to school as usual.

But imagine a different scenario: exam weeks. Students are sitting in the library, testing themselves with their well-prepared flashcards, checking their understanding of the most difficult topics with each other, and drawing some mind-maps from memory to test their knowledge. Because they continuously prepared during the semester, students feel less stressed, still make time for sports and good food, and after their exams, they happily enter their vacation. Coming back to university after summer, teachers start the course with a recap quiz of the last year, and surprisingly students still show a decent understanding of what they have learned in the past. Building on a solid basis of prior knowledge, students can continue to their next semester.

When asking students how they typically study, 60-80% report using passive strategies, such as rereading, summarizing, or highlighting. Most students cram the majority of their preparation into the last weeks before the exams. This way of studying, however, stands in contrast with what has been identified by cognitive and educational psychology to facilitate lasting learning: desirable difficulties. Desirable difficulties are learning conditions that make learning initially more difficult (and effortful), but enhance learning outcomes in the long-term, and thus are desirable. Examples of desirably difficult strategies are retrieval practice (e.g., testing yourself with flashcards or old exam questions) or distributed/spaced practice (e.g., spacing out your study sessions over time, instead of cramming 8 hours of studying the day before the exam, studying 1 hour in the 8 days before the exam). While the benefits of these strategies have been proven time and again, the million-dollar question is: How can teachers support students to actually use these desirably difficult strategies during their self-study?

With the aim to bridge the gap between what research shows and what students do, we developed the ‘Study Smart’ program. Together with a diverse team from all faculties of our university, we developed a training program for first-year students consisting of three 2-hours-sessions spread out over several months:

- Awareness: making students aware of what works and what doesn’t, what are effective learning strategies and why do they work?

- Practice: helping students put their knowledge into practice with relevant exercises on effective cognitive strategies (e.g., how to make flashcards or how to write an active summary) and planning strategies (e.g., how to make a realistic weekly plan)

- Reflection: peer-support session with a reflection on difficulties during implementation and how to deal with these challenges.

The Study Smart program has now been implemented in most of our bachelor programs. It is usually integrated into the academic skills training or the mentor program and is given by mentors, tutors, or student counselors. Outside of our own university, the program has been implemented nationally and internationally (e.g., Portugal, Barbados, US, Belgium). We gained a lot of experience in how to implement and adapt the program to different contexts through continuous evaluation and redesign of the program. We investigated the effects of the Study Smart program on students’ knowledge and use with mixed methods and showed that the Study Smart program supported lower-achieving students to reach competence over the year. Here, we want to share with you our six crucial steps in supporting students to study smart.

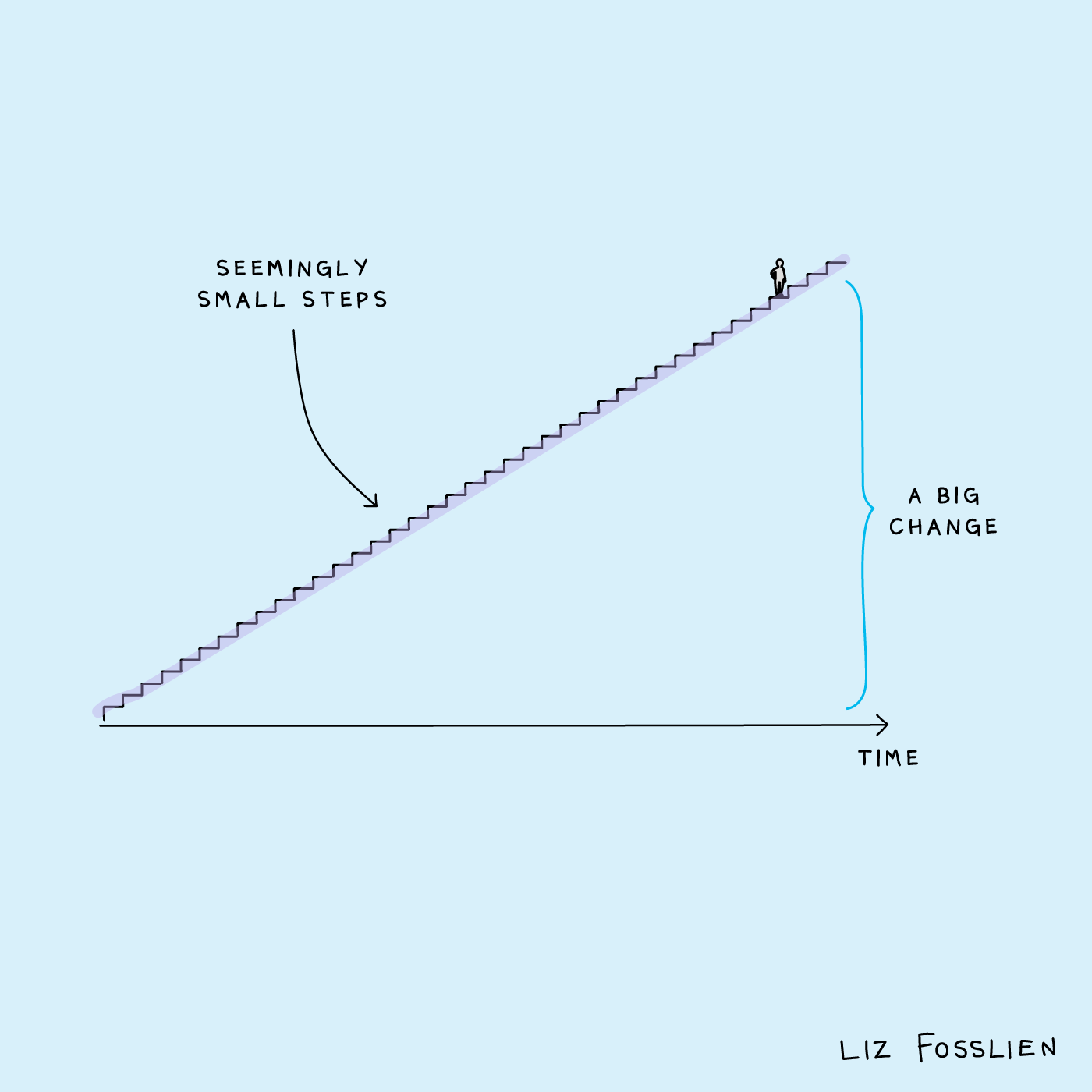

1. Start with students’ existing study habits

First: Every student has strong study habits. Developed over their whole school career, starting from primary school up to high school, students needed to learn in some way. For students who enter higher education, their way of studying was clearly good enough to get them to where they are. Second: Changing old habits is hard. We all recognize this when trying to go to the gym twice a week, staying away from the ice cream when watching TV, or starting a flossing routine. What helps with building new habits, is to start with existing habits and change from there in small steps. Change is always hard and even harder when you try something effortful, like desirable difficulties. That is why in Study Smart, we start with a brainstorm about how students study now. Do they solely rely on copy-pasting summaries or do they already engage in more active strategies, such as asking themselves questions? Then, it is time to reinforce these effective strategies and slowly adapt the less effective ones. Students do not need to leave everything they did before behind, but should try to add small things to existing habits. For example, ending each summary with three practice questions about the topic or adding a 5-minute recap-session (e.g., what was this summary about?) before starting to reread it again.

2. Teach students directly about effective learning strategies

Without knowing ‘what works’, it is hard to do the right thing. While we assume that most students know the best way to learn, most do not. Some might have learned in high school about ‘learning how to learn’, others did not. To create equal opportunities for everyone starting in higher education, it is important to teach students directly about effective learning strategies: How does learning work? Why is it important to be an active learner and which learning strategies exist? Why are desirable difficulties effective and what are the most effective learning strategies according to science? Bringing cognitive psychology to the classroom can be fun, but it is also important to ‘practice what you preach’. Make the instruction interactive (e.g., let students first list all strategies they know and sort them along their effectiveness) or end the session with a practice quiz to ensure that the information has been understood.

3. Help students gain insight into learning myths and misleading experiences

Many students have strong ideas about what works best ‘for them’. Everyone is unique and therefore needs their unique way of studying, right? Well, as this video by Veritasium nicely explains, the biggest myth in education is still ubiquitous and needs to be busted: the learning styles myth. The trick is not to find out whether students are a visual or auditory learner (spoiler alert: neither), but to use the right strategies that help improve retention and understanding. What is actually effective is universal for most people: active and desirably difficult learning strategies. However, these desirable difficulties can become even more difficult because immediate experiences during learning can be misleading.

Everyone can probably recognize this experience: you read a summary several times and the information seems familiar, so you think you understand everything well. But then you sit in the exam and although you know that you read something about that topic in your summary (and you know that you marked it in yellow), you cannot come up with the correct answer. This phenomenon is called ‘the fluency illusion’. Because something feels fluent and familiar, it is not necessarily a sign that you have mastered it. Or, maybe you can recognize this experience: when testing yourself or trying to remember something you learned last week, it feels very difficult. This experienced-vs-actual-learning-paradox can make it quite tricky for students to accurately judge what they have learned. When leaning on immediate experiences during learning, students are likely to make poor study strategy decisions. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary to help students gain insight into these learning myths and make them aware that a feeling of difficulty is actually a sign of learning.

4. Address and alleviate uncertainty

Every change comes with uncertainty. This holds also for changing the way you study. Even when students are aware that experiences during learning can be misleading, if studying feels hard, keeping up that behavior is even harder. This is even more true when students are uncertain about whether they will pass their exams with the new strategies or how to actually put these strategies into their daily practice. In Study Smart, we address this uncertainty in several ways. In the practice session, students practice different effective strategies with their own learning materials with guidance and support from teachers and peers. In the reflection session, students serve as peer-coaches for each other and discuss common challenges and how to overcome them with the critical incident technique. One critical point here is also the collaborative learning aspect: learning from and with each other, holding each other accountable, or recognizing the same struggles can motivate students to get started and keep going.

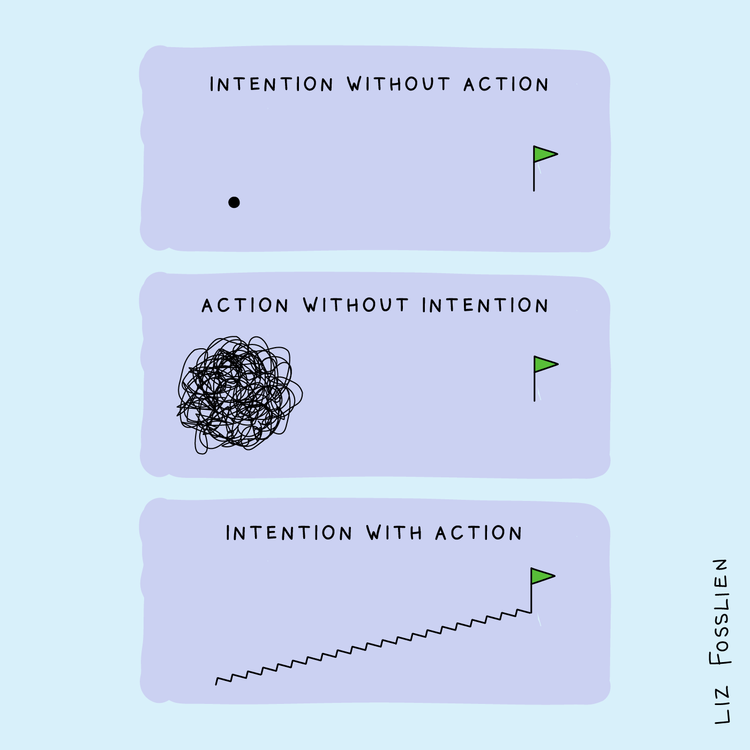

5. Set clear goals

By now, students should be aware of their own study habits and the efficacy of different learning strategies, and they have gained experience putting effective strategies into practice. Students might have developed the intention to study more effectively by now, but without clear goals and an action plan on how to achieve these goals, these intentions might fade quickly. Especially with the stress of an upcoming exam period or other distracting factors, not having clear goals and knowing why these goals matter might lead to students falling back into old and ineffective habits. In Study Smart, we try to support students in setting clear and achievable goals at the end of each session, and following up on these during the next session. In cases where Study Smart is integrated into students’ mentor programs, these goals are followed up on during individual meetings. Mentors can help students reflect on their goals and progress, provide support on how to achieve these goals, and help with accountability.

6. Provide guided practice and context-embedded support over time

The last step in supporting students to study smart might be the most important but also most difficult one. We have seen that change does not happen overnight and thus we recommend supporting students continuously and above a one-time ‘learning how to learn’ workshop. The longitudinal support, including reminders, helping students reflect on and adapt their goals and strategies, and scaffolding effective learning strategies use, is crucial for developing effective learners. When doing so, it is important to embed the principles of active learning and desirable difficulties as much as possible in courses and teaching practices. Stimulating practice testing or distributed practice as a teacher, such as starting each lesson with a short recap quiz of the previous topic, course, or semester, can help students to stay on track and see the relevance of these strategies. Providing students with accurate feedback on their learning and self-regulation process during an individual mentor meeting can help students to adapt to different situations and contexts and stay motivated despite difficulties.

Recommended reading

Biwer, F. & de Bruin, A.B.H. (2023). Teaching Students to ‘Study Smart’ – A Training Program based on the Science of Learning. In C. E. Overson, C. M. Hakala, L. L. Kordonowy, & V. A. Benassi (Eds.). In their own words: What scholars want you to know about why and how to apply the science of learning in your academic setting (pp. 419-433). Society for the Teaching of Psychology.