Learning doesn’t happen in a vacuum, so why do our recommendations for “strategic learning” ignore context?

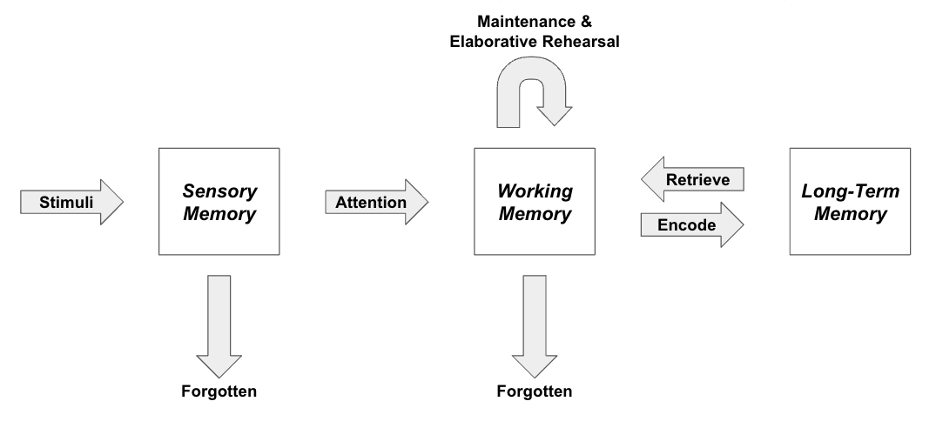

When we think about investigating learning – what it is and what processes are involved – we might think about it in ways similar to how Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968) proposed in their model of human memory:

Maybe you imagine conducting studies with eye trackers or launching experiments on online platforms where you try to isolate certain processes as students engage with unfamiliar stimuli. And when we transfer the results of these investigations into the classroom, we might encourage students to test themselves, to space their practice, or to interleave. While all well-intentioned recommendations, they leave out an important consideration of learners’ lives: their contexts.

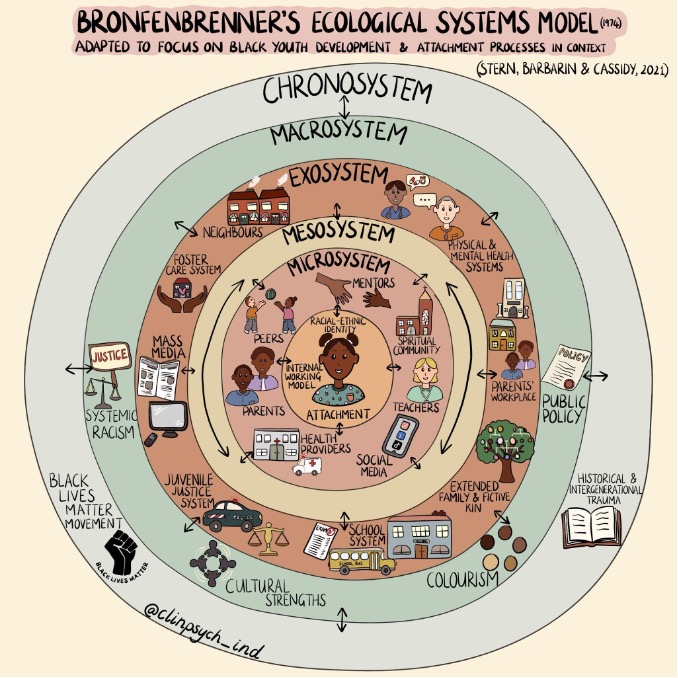

Moving beyond considering learners as information processors, we might make use of frameworks such as the 4E approach to cognition or culturally adapted approaches to Bronfenbrenner’s (1974) ecological systems theory. With these conceptualizations, we can begin to see how learning processes shape and are shaped by their broader contexts.

Visual representation of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model adapted by Stern et al. (2021) to focus on Black youth development and attachment processes. Illustrated by @clinpsych_ind.

While some might say that we all have the same 24 hours in a day as Beyoncé, differing responsibilities and access to resources make that an unfair qualification. We cannot feign that at a predominantly white institution, a white student who came to college with friends from their high school graduating class and whose parents support them with rent and in other ways will have the same learning experiences as a student who goes home on the weekends to support their family, and who works a part-time job in addition to managing their course load, or a student with a learning disability. Making generalized learning recommendations for these two students, without considering their contexts may be harmful.

Drawing from cognitive load theory, individuals have limited ability to attend to information. Situational demands such as anxiety and classroom distractions can impact this capacity. What we must not lose sight of is how other situational factors, such as sense of belonging, stereotype threat, financial privilege, and sleep can impact students’ ability to learn and retain information. Systems of privilege and oppression operate inside and outside of the classroom and impact different students in different ways. To ignore the impact of these systems on students’ learning is irresponsible. As educators and researchers, we cannot control the things that occur outside of the classroom, but it should be our ethical responsibility to promote and foster educational equity in all domains.

The Science of Learning: A Meaningful Foundation

Learning science researchers are taking up a meaningful goal of understanding effective ways to teach and learn. Doing so may help to position educators to teach in more accessible ways and to encourage students to engage with strategies that help them reach their learning goals while balancing the other goals they hold. This field has given us great insights into learning and memory processes while taking a relatively “objective” approach. We do not necessarily believe that more process-level or cognitive-focused research must take up an individual’s identities to meet calls; however, in order to bolster equity-focused work, we must acknowledge how certain approaches can rectify deficits or perpetuate them. We argue for recognizing the importance of identity and context in the recommendations associated with relevant findings, moving beyond individual-focused framings.

Individual vs. Systems: Shaping Recommendations and Approaches

When we think about learning-based research, many scholars take up individual approaches to their investigations. Especially in the context of interventions, it is much easier for there to be changes made at the individual rather than systemic level. While these findings are helpful to inform broader change, they can fall short. Researchers need to ask themselves for whom does this intervention work? When students are told that they just need to test themselves or teach concepts to a friend to advance their learning, we can find ourselves in a “work harder/smarter” territory. Without considering the context or the systems in which students exist, we may be telling students to pull themselves up by their bootstraps when they are wearing flip-flops. In addition, we want to recognize the disparate levels of support and resources teachers have within their districts or classrooms. If we, as researchers, aim our interventions at the teacher level, we may be placing additional burdens on an already burnt out population. Moreover, leaving our recommendations directed at the student or teacher level displaces responsibility for creating larger organizational and systemic changes that can reduce educational inequities.

Research

The science of learning field has produced an impressive body of scholarship considering cognitive processes and mechanisms. But what if students are not learning anything? Do we have evidence-based methods when the conditions are not “ideal?” What are learning strategies that work regardless of societal privilege? If our goal is to improve learning and retention for everyone, we need to conduct more research on people who have fewer privileges rather than being privilege-evasive or overly generalizable. While objectivity in the field is not necessarily bad, objectivity without recognizing the limitations of studies that take this approach is problematic. Instead, we need to be explicit about context, about our participants, and about the assumptions and biases we, as researchers, hold.

Educational fields, like curriculum and instruction, have years of experience researching and understanding ways that systems impact students’ learning and memory. Just like cognitive sciences, curriculum and instruction addresses students’ learning and learning experiences. We advocate for an increase in interdisciplinary work. While certain concepts we have discussed here might be new or unfamiliar to cognitive psychologists, they have been enacted and practiced in other fields for a long time. What are ways that knowledge from other fields can be combined with cognitive science and leveraged to create more culturally responsive frameworks of learning?

Educational Spaces

Moreover, beyond promoting and modeling individual strategies backed by the science of learning, those of us in power must begin to remove the barriers that students face and work to create environments that allow them to thrive. Tackling systemic issues can be daunting and will take time. However, making small changes in the classroom or lab spaces is accomplishable. Before we dive in with specific recommendations, we do want to recognize how placing the onus on teachers to create change in their classrooms.

We encourage educators to take steps, even small steps, toward progress. For example, set aside intentional time to build a classroom community during the first few days of class. Doing so may help to promote psychological safety, build relationships that can be leveraged when later needing help, and bolster engagement. In addition, establishing clear classroom or lab expectations so no one is left uncovering hidden curriculum or norms is important. Students may not know the purpose of office hours, so explaining their intended use may promote visits. Communicating your teaching philosophy or orientation and why students are being assessed the way they are can allow for purposeful engagement. All of these suggestions, we believe, can help to provide the conditions that support learning.

Who needs the toolkit?

At the start of the new semester, many teachers and educators will turn to learning science research to find recommendations for how their students can reach their academic goals. What we are calling for here is a reversal of this narrative. How can we, those of us conducting the research, in various positions of power, conduct work that pushes systems to change so that the onus is not on the students or teachers to take on additional burdens? Moving beyond individual approaches to considering context may allow for more responsible future recommendations. When we think about building a strategic learning toolkit in support of educators and students, we cannot continue to ignore who they are or the systems they are in.