Understanding how people learn and apply their knowledge to novel situations has been a focus of cognitive science since the early 1900s. To capture this phenomenon, many theories of knowledge transfer have emerged, and most “suggest that the likelihood of transfer is dependent upon the likelihood of encountering a relevant bit of information or skill during the memory search process” (Royer, 1979, pp. 62). However, these theories do not capture how transfer also involves motivation, which guides learners in how they engage in learning (e.g., Nokes & Belenky, 2011). Learners can start and finish a task with various levels and types of motivation that guide how strategic they are at the given task as well as future tasks. While other authors in this Digital Event have described various cognitive approaches to student learning, here, I describe how students can be motivationally driven to strategically further their knowledge retention and transfer. To do so, I integrate research from cognitive and educational psychology around the self-regulation of learning.

Strategic learning or effective self-regulation is when students are cognitively, metacognitively, and motivationally in control of their learning. They not only have to know which cognitive and metacognitive strategies to use, but they must also be motivated to use them throughout the learning process. For example, when students begin a task, they draw from their motivational beliefs and goals; during the task, they might employ motivational regulation strategies to maintain or increase their motivation; and after a task, they might adapt their motivational goals, beliefs, and strategies for the next task. Motivating students to learn can also range from motivating them to learn the content (see Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2016 and Wigfield et al., 2021) to motivating them to employ cognitive strategies that help them learn the content (see McDaniel & Einstein, 2020 and Zepeda et al., 2020). As one can see, there are many places in which motivation can be supported or activated. From an instructor’s perspective, it can be a daunting task, but if we remind ourselves that our goal is to support our learners and break it down into smaller tasks, it can be much more manageable. One way to break it down into smaller tasks is to think about how we design our courses. Motivation can be supported in the assessments and assignments we administer and the feedback we provide within our courses. Below, I provide examples within each area and describe how a subset of motivations can be supported.

Assignments and Assessments

Some of the assignments and assessments we give students naturally support strategic learning. For example, assigning low-stakes quizzes throughout the course provides students with opportunities to engage in retrieval practice and allows opportunities for students to monitor their understanding. We can also maximize the use of these quizzes by spacing and interleaving the content. To add a dash of motivation, there should also be opportunities to retake the quizzes to promote mastery-approach goal orientations among students. If we want them to master the material, then there must be opportunities for students to improve and focus on learning as much as possible.

We can also use assignments that support the use of other strategies, such as explanation and comparison. To add a different flavor of motivation, we can provide elements that provide autonomy and tap into their interests. For example, an assignment that my students have enjoyed involves defining a concept in their own words, providing an example of the concept, and then selecting a song that represents the concept and explaining how it represents that concept. This allows students autonomy over picking songs that interest them while enhancing their understanding of the content.

Across assignments and assessments, it can be tempting to assign higher-risk exams and projects. However, this can often be overwhelming and anxiety-provoking. Thus, consider segmenting large assignments into smaller, incremental pieces with deadlines throughout the course so students can see their progress and have multiple opportunities to receive feedback to improve. As for exams, adding low-stakes quizzes throughout the course can incrementally prepare them for a more extensive knowledge assessment. These structural changes to assignments and assessments provide an opportunity for students to master the content and feel more self-efficacious.

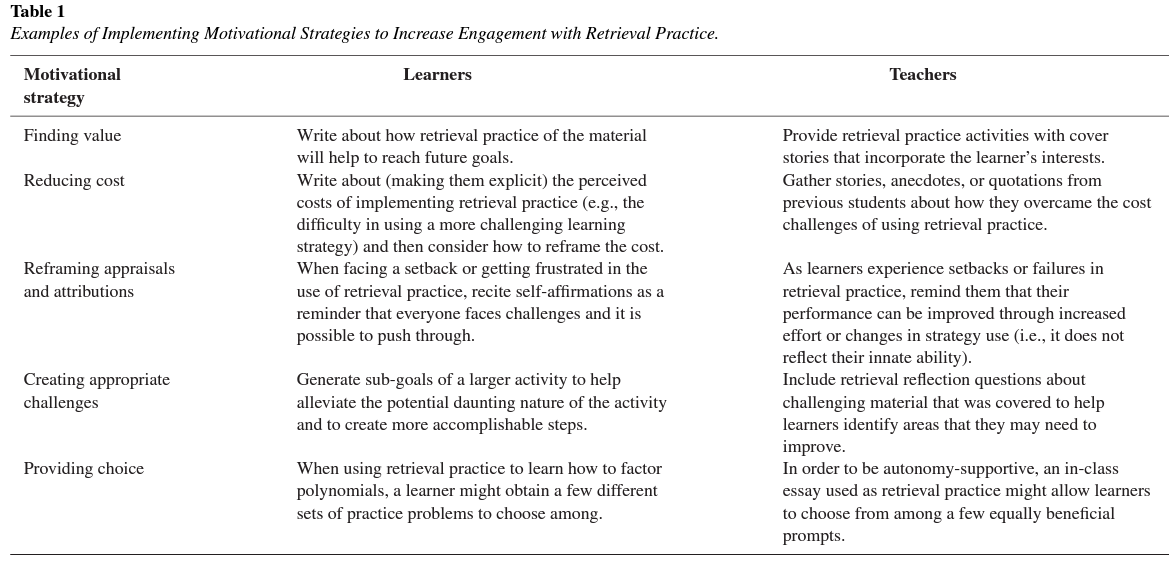

The three examples above involve motivating students to learn the content, but another approach is to design assignments that motivate students to independently use strategies to enhance their learning when studying for quizzes and exams. For more concrete examples, see the table below.

Table 1 from Zepeda et al. (2020)

Feedback

Although decades of research have shown the benefits of feedback, sometimes, as instructors, we might need a little motivation to provide quality feedback to our students. So, let me paint a rosy picture to demonstrate the utility of taking the time and effort to provide such feedback. In a recent study, we surveyed 378 undergraduates from various institutions about the types of assignments and assessments they received in their courses, the types of feedback they received, and their motivational perspectives of feedback. Even though students reported that they received a wide range of feedback depending on the type of assignments and assessments they were given, they also reported that they valued and used the feedback they received in their courses. It is important to note that they tended to report that feedback was personalized to them, and the better they performed in their courses, the more positive views of feedback they had. Additionally, when the feedback was personalized, it also stated what was incorrect, and included commentary about why it was incorrect and/or encouragement, suggesting that these might be essential elements in why these students were motivated by the feedback provided in their courses.

Moreover, even when students receive frustrating feedback, they report employing various motivational regulation strategies. In fact, the most common motivational regulation strategies they employed tended to involve those that tap into adaptive motivational beliefs and goals. These included self-efficacy self-talk (reminding themselves that they are capable of improving), mastery-approach self-talk (reminding themselves they want to learn as much as possible), attainment value self-talk (reminding themselves of the importance of doing well), and utility value self-talk (reminding themselves that it will help them reach their career goals). These findings demonstrate that students can also be strategic in how they process and regulate their use of feedback.

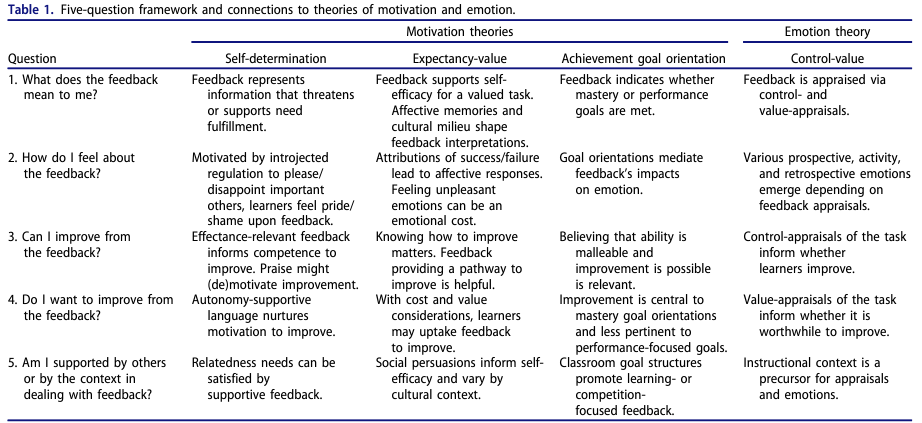

Fong and Schallert’s (2023) recent review echoes some of these findings. In their review, they wonderfully capture how feedback can support several aspects of motivation (and emotion) by asking five questions that instructors can reflect on as they craft their feedback: (1) What does feedback mean to students? (2) How does feedback make students feel? (3) Can students improve from the feedback? (4) Do students want to improve from the feedback? and (5) Are students supported by others or the context in dealing with the feedback? See their table below for examples of how answering these questions based on different motivational theories can be accomplished. And while you are reflecting on how you provide feedback, it is always imperative to check your biases and think about whether the feedback you are providing is equitable. This gem just dropped, and although it is focused on middle school contexts, much of it still applies to college students.

Table 1 from Fong & Schallert (2023).

In sum, strategic learning can be supported and fostered via motivation. Within the classroom, there are several ways instructors can motivate students to engage in strategic learning. Hopefully, I sparked some motivation to integrate aspects of motivation within your courses.

Recommended Readings

Fong, C. J., & Schallert, D. L. (2023). “Feedback to the future”: Advancing motivational and emotional perspectives in feedback research. Educational Psychologist, 58(3), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2134135

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Patall, E. A., & Pekrun, R. (2016). Adaptive motivation and emotion in education: Research and principles for instructional design. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(2), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732216644450

McDaniel, M. A., & Einstein, G. O. (2020). Training learning strategies to promote self-regulation and transfer: The knowledge, belief, commitment, and planning framework. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1363–1381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620920723

Wigfield, A., Muenks, K., & Eccles, J. S. (2021). Achievement motivation: What we know and where we are going. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 3(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-050720-103500

Zepeda, C. D., Martin, R. S., & Butler, A. C. (2020). Motivational strategies to engage learners in desirable difficulties. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(4), 468–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2020.08.007