We rarely listen to just one stream of information at a time. Whether we are at a dinner party, on a crowded bus, or talking on the phone while walking down a busy street, more often than not there are multiple voices that compete for our attention.

People are generally very good at focusing on the relevant voice and filtering out the many competing channels. One of the factors we rely on to achieve this filtering is familiarity with the talker’s voice. Unsurprisingly, you would find it easier to make out what your spouse is saying in a crowded bar than a random stranger or casual acquaintance.

But what if you actually wanted to listen to that acquaintance while your spouse is talking to someone else? It is easy to see how familiarity would benefit comprehension, but how would familiarity affect our ability to filter out that channel so we can attend elsewhere?

The famous cocktail party effect suggests that a familiar stimulus might be difficult to ignore. The cocktail party effect refers to the fact that you may be quite able to ignore distracting conversations at a party while trying to focus on a single speaker, but the moment someone merely whispers your name at the other end of the room you will instantly—and perhaps involuntarily—shift your attention to that other conversation.

However, it could equally be argued that familiarity with a speaker may make it easier to filter out an on-going distraction. Perhaps we are not only better at understanding our spouse than a random stranger, but also better at ignoring him or her.

A recent article in the Psychonomic Society’s journal Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics examined those two possibilities in an irrelevant-speech task, in which listeners must remember a sequence of task-relevant stimuli while task-irrelevant to-be-ignored speech is presented during memory retention.

The team led by Jens Kreitewolf sought to differentiate between these two options, while additionally also manipulating the degree of familiarity with the potential distractor. To manipulate degree of familiarity, Kreitewolf and colleagues recruited two groups of participants. One group consisted of students who had received classroom instructions by one of the two talkers used in the experiment. This group therefore had an intermediate level of familiarity with the voice of the talker, having spent a minimum of 9 lessons with the talker. The second group comprised close friends and family members of each of the two talkers, who therefore had a high degree of familiarity with the voices.

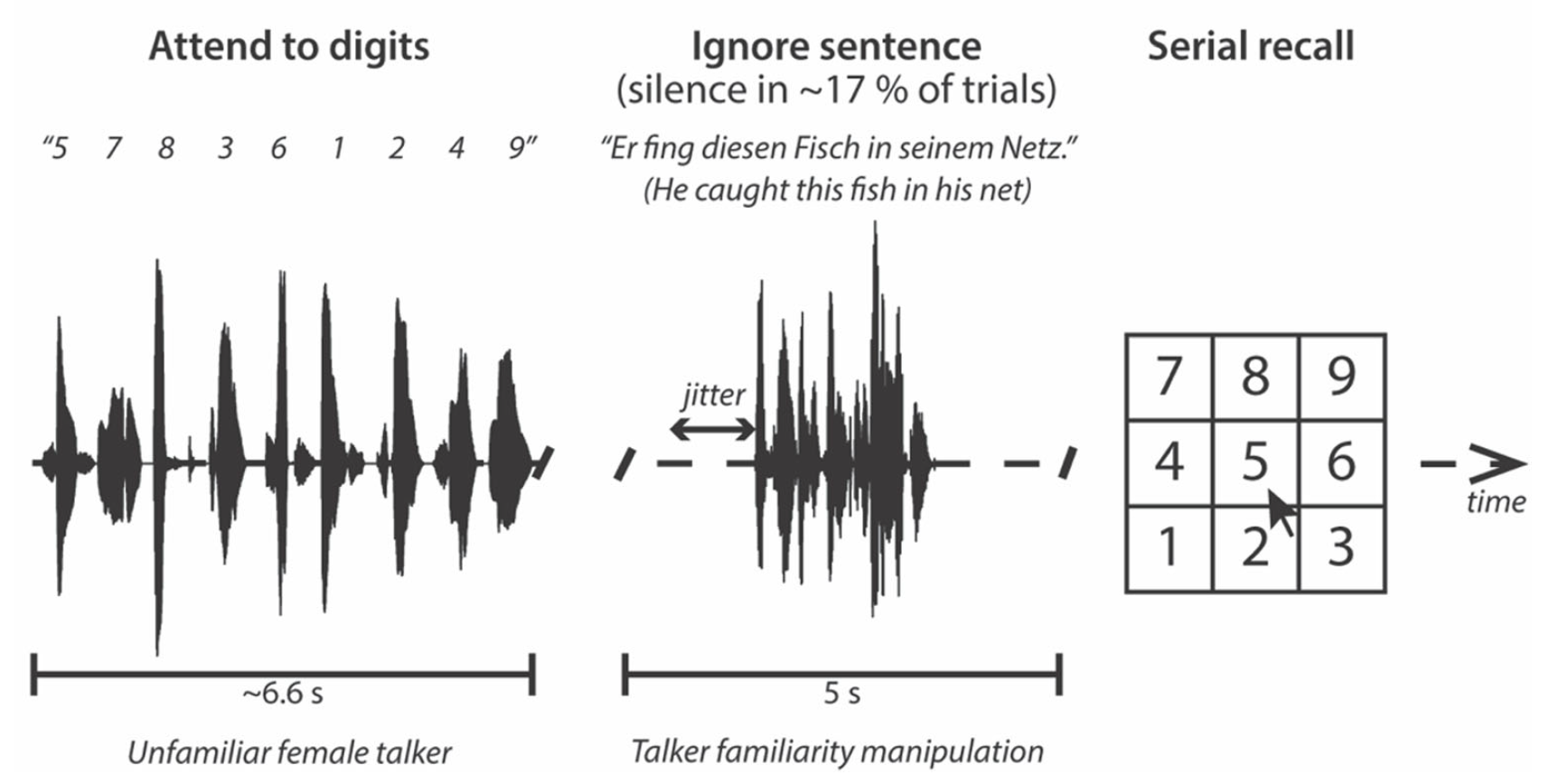

Participants listened to a sequence of random digits that was presented for memorization by an unfamiliar female speaker. Following list presentation, participants listened to distracting sentences spoken by one of the talkers that were presented at a random point during the retention interval. After the 5-second retention interval had elapsed, participants recalled the sequence of digits in their correct order via a numeric touchpad. The figure below shows the procedure of the experiment.

The crucial manipulation occurred across blocks of 30 study-test trials. Two of the blocks involved the familiar talker (i.e., close friend or instructor, depending on group) and the other two the unfamiliar talker (i.e., the other talker who was neither a friend nor instructor). Within each block, the distracting material was withheld on 5 trials, therefore permitting an assessment of the role of expectation—generated by the remaining 25 trials of the block with the same familiar or unfamiliar talker—on distractor-free memory performance.

As expected, memory was significantly poorer for the trials that contained distracting material than for the distractor-free trials. This effect is yet another demonstration of the irrelevant-speech effect and is of little interest other than to show that the experiment “worked”.

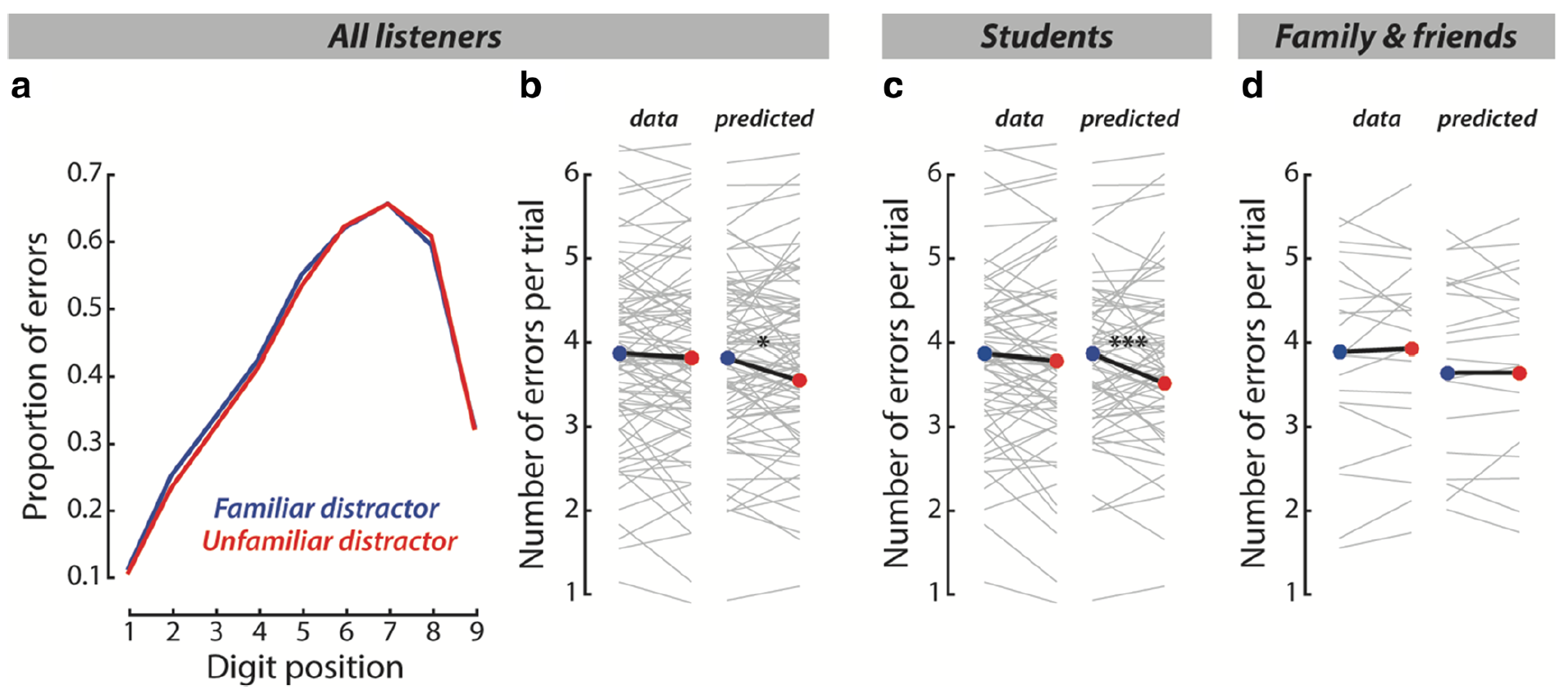

The more interesting results involving the role of talker familiarity are shown in the next figure.

The panels of particular interest are b, c, and d, which show, respectively, the effect of talker familiarity for all participants overall (b), and separately for students of the talker (c) and friends (d). Blue dots represent the average performance for the familiar talker and red dots for the unfamiliar talker (the gray lines in each panel represent individual participants).

It can be seen that there was no effect of familiarity on participants who were highly familiar with the talker’s voice (panel d). For participants who were moderately familiar with the talker, there was a significant effect of familiarity, such that the familiar distractor produced more errors in memory performance than the unfamiliar distractor. Listening to a voice you know but are not terribly familiar with is more distracting than an unfamiliar voice or a voice you are intimately familiar with.

In a further analysis, the researchers showed that this disruptive effect of modest familiarity also occurred on the trials on which no distraction was present. The mere expectation of a modestly-familiar voice was sufficient to impair memory even if that voice was then, surprisingly, absent on a particular trial.

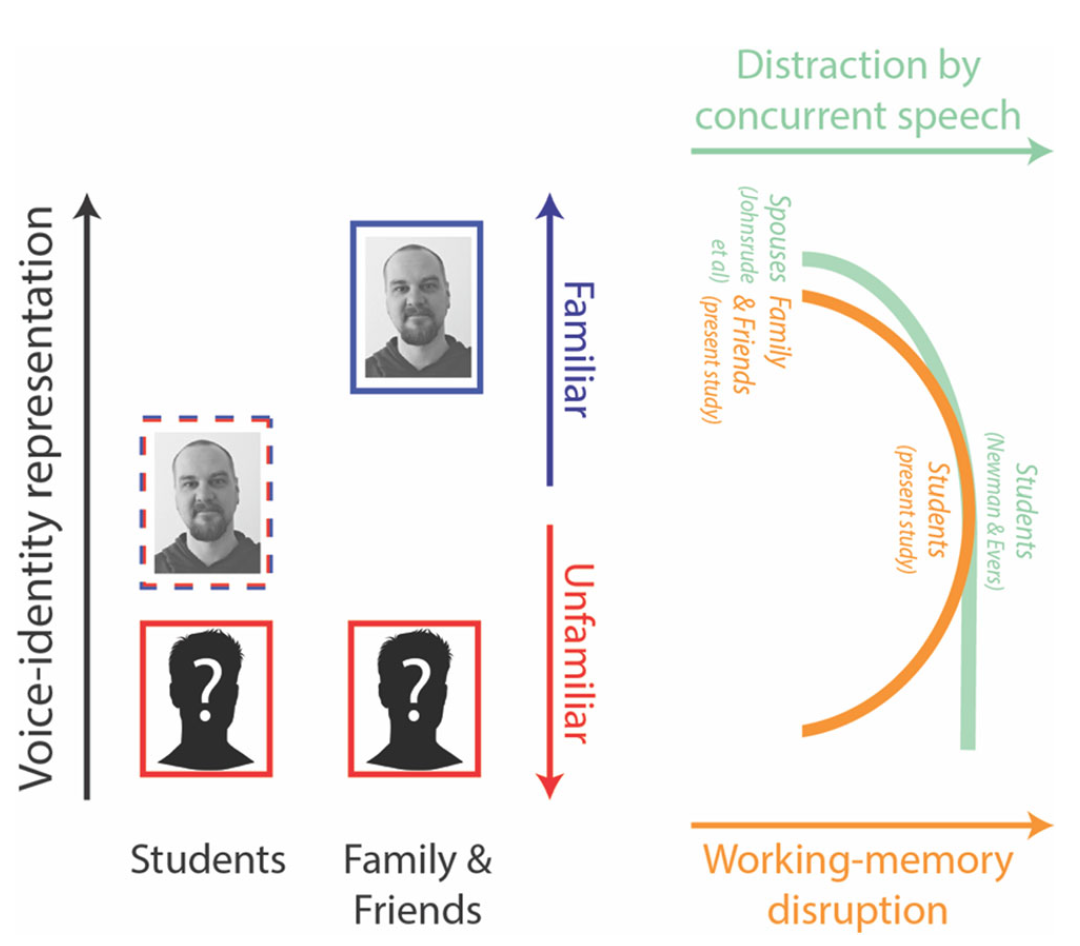

Kreitewolf and colleagues present a model to explain their findings, and that of other findings in the literature that have appeared contradictory. The model is shown in the next figure.

The key component of the model is the quality of the representation of vocal identity. Previous voice-identity research has established that a high degree of talker familiarity is needed to create a stable representation of identity. Moderate familiarity, by contrast, creates uncertainty about identity. Kreitewolf and colleagues argued that this uncertainty, in turn, amplifies disruption of memory compared to a completely unfamiliar distractor.

Taken together with existing research, these data suggest that we are not only better at understanding our spouse than a random stranger, but also better at ignoring him or her.

Psychonomics article highlighted in this post:

Kreitewolf, J., Wöstmann, M., Tune, S., Plöchl, M., & Obleser, J. (2019). Working-memory disruption by task-irrelevant talkers depends on degree of talker familiarity. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 81, 1108-1118. DOI: 10.3758/s13414-019-01727-2.