Sarcasm, a type of irony, is inescapably embedded in the internet today, with ironic language of some kind being ubiquitous on Facebook, Twitter, in blogs, in news articles, and more. Computers, unlike people, often fail to detect sarcasm, which has the notable quality of often meaning nearly the opposite of what was written. For example, if I say, “I looove having a headache”, you would likely infer that I very much do not love having a headache.

Being able to correctly understand sarcasm is therefore a highly valuable skill. Without supporting context, sarcasm can be very difficult to understand and interpret, slowing readers down if they hope to understand the writer’s meaning. Evidence that readers slow down when reading sarcastic sentences comes primarily from eye-tracking studies, which measure where someone is looking. Typically, psycholinguists present sentences or other kinds of visual displays containing photos or line drawings. We then use the coordinates of where someone is looking to infer what they were trying to process. We can quantify how the eyes move in a number of different ways.

Here are some important eye tracking measures used in psycholinguistics:

- First fixation duration: How long we look at a word the first time we read it.

- First-pass duration: How long we read the word in total before we reach the end of the sentence.

- Total time: How long we read the word in total for all of the time the sentence is on the screen, including look-backs.

- Regression: Looking back to a word in a sentence.

If you are having a hard time visualizing what eye movements look like for text reading, you can get a better sense by watching the video below from SR Research:

You might note some interesting patterns even in this short video. First, many movements appear to be big jumps between words, which are known as saccades (derived from the Latin word for jump). Second, readers’ eyes do not land on random parts of the word, but rather somewhere slightly in the middle. Third, the reader in this video is skipping most of the smallest words, known as function words, which carry little meaning.

In the processing of non-sarcastic text, for example in temporarily ambiguous sentences like “While Anna dressed the baby spit up on the bed”, readers will sometimes return to an earlier part of the sentence. It is unclear, however, why readers go back to earlier parts of the text at all, because another viable option is to simply read difficult information for longer.

Perhaps these regressions happen because readers cannot keep an entire text in memory?

Readers might go back to try to make sure the reading is correct―this appears to be a conscious decision that readers make. Even if readers do not have a perfectly accurate memory of the text, they do have a good memory for where words and ideas are in the text, which requires a memory for the spatial layout of the words.

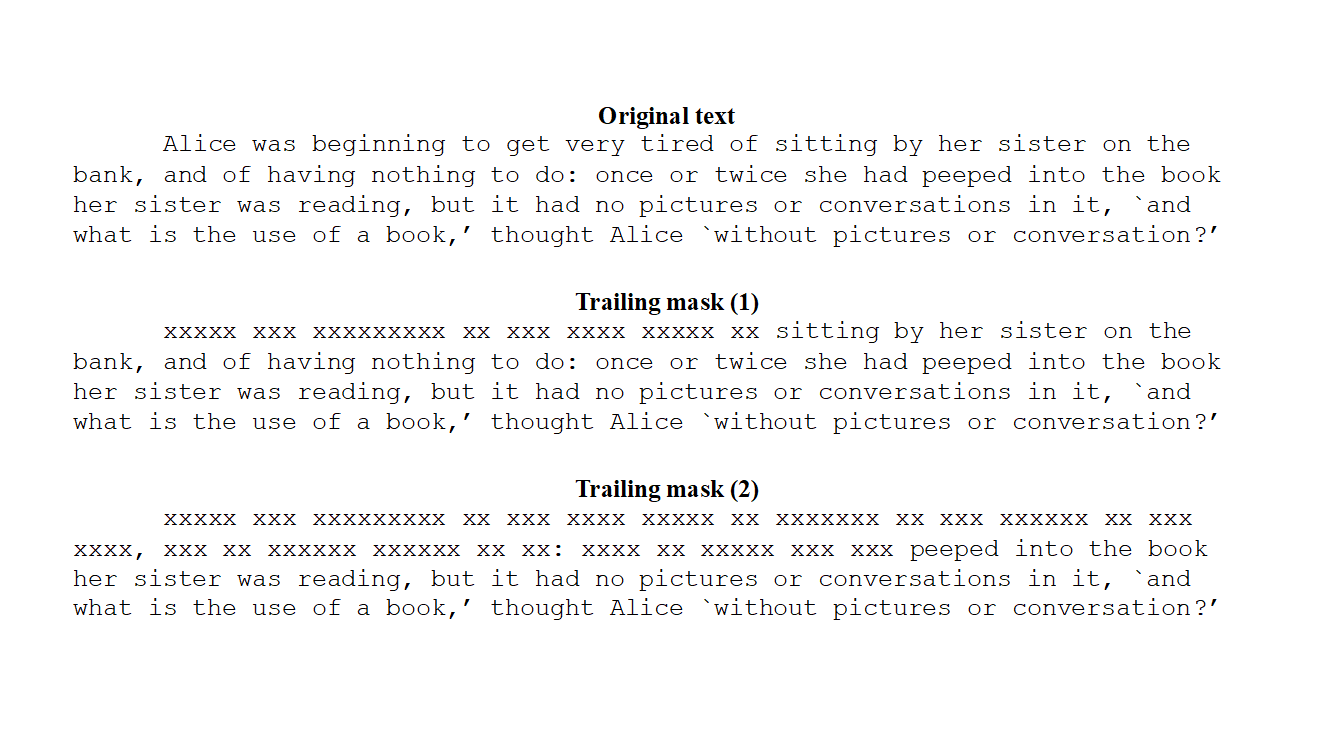

An important manipulation in experiments that tests regressions effectively erases previously-read information from view in what is called a “trailing mask.” The way this works is that as soon as I move my eyes away, the text disappears and is replaced by x’s. Typically, this doesn’t disrupt reading directly, but it does mean that readers cannot look back to the text to re-read. For example, the figure below demonstrates how this might look if we blocked out entire sentences once a reader had started moving on to the next sentence:

When processing sarcasm, readers might also look back for similar reasons―to ensure that they got the right meaning. Individual differences in cognitive skills like working memory capacity support this idea: People with high working memory capacity tend to re-read before moving on, while people with lower working memory tend to jump back to an earlier part of the text. The exact mechanisms that underlie this are still unknown. Similarly, people who are better at detecting emotions in non-linguistic tasks (e.g., gambling) also tend to be better at detecting sarcasm in texts.

In a recent article published in the Psychonomic Society’s journal Memory & Cognition, researchers Olkoniemi, Johander, and Kaakinen conducted an experiment looking at these individual-differences factors as well as a unique variant of the trailing mask to get a better handle on where and when people look back in texts when they encounter sarcasm.

In their experiment, Olkoniemi and colleagues manipulated the “trailing mask” paradigm by masking not just preceding words, but instead entire preceding sentences. That way, readers could look back within a sentence, but they were never able to re-read a previous sentence once they started a new one. The researchers were interested in (1) whether the mask influenced the strategies that readers employed for reading the texts and (2) whether individual differences affected these strategies.

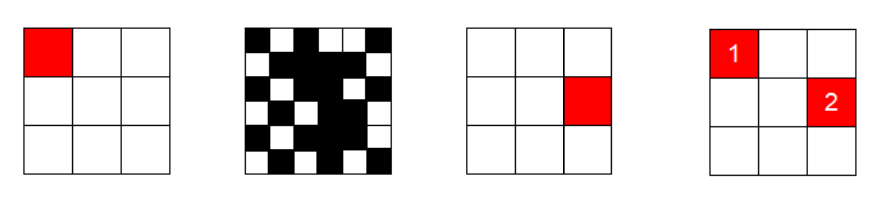

For individual differences, the authors obtained a number of measurements that have correlated with sarcasm comprehension before, but they focused especially on spatial working memory. Because readers build a representation of the spatial structure of the text (i.e. where words and sentences are in a paragraph), spatial working memory allows readers to know where to look back if they encounter difficulty. To quantify this, Olkoniemi and colleagues used the Symmetry Span Task (SSPAN) in which participants recall a sequence of red squares in an 8 x 8 grid, followed by a random mask of white and black squares. At recall, participants click on the squares in the order in which they were read. The more squares someone can correctly label in order, the higher their SSPAN is. Below is an example that uses a small 3 x 3 grid for simplicity:

The top left corner is colored red, followed by a mask, followed by the rightmost middle square in red. Participants have to remember the locations. Then, at “recall” participants indicate the squares in an empty grid in the order in which they appeared (shown here by the numbers).

In many reading studies, stimuli are divided into several sections. First, most sentences have a target word or region of interest―where the experimenters believe readers will look back to. Second, there is usually a spillover region, which comes later in a text. Finally, there are other regions that are earlier or later in the text. Olkoniemi and colleagues analyzed how long people looked at the target before moving forward (first-pass reading times), look-backs to the target area (regressions), and memory for the text (comprehension question accuracy). To understand how much sarcasm drives these effects, the authors compared sarcastic utterances (e.g. “I looove having a headache”) to literal ones without a special ironic meaning (e.g. “I love cheddar cheese”).

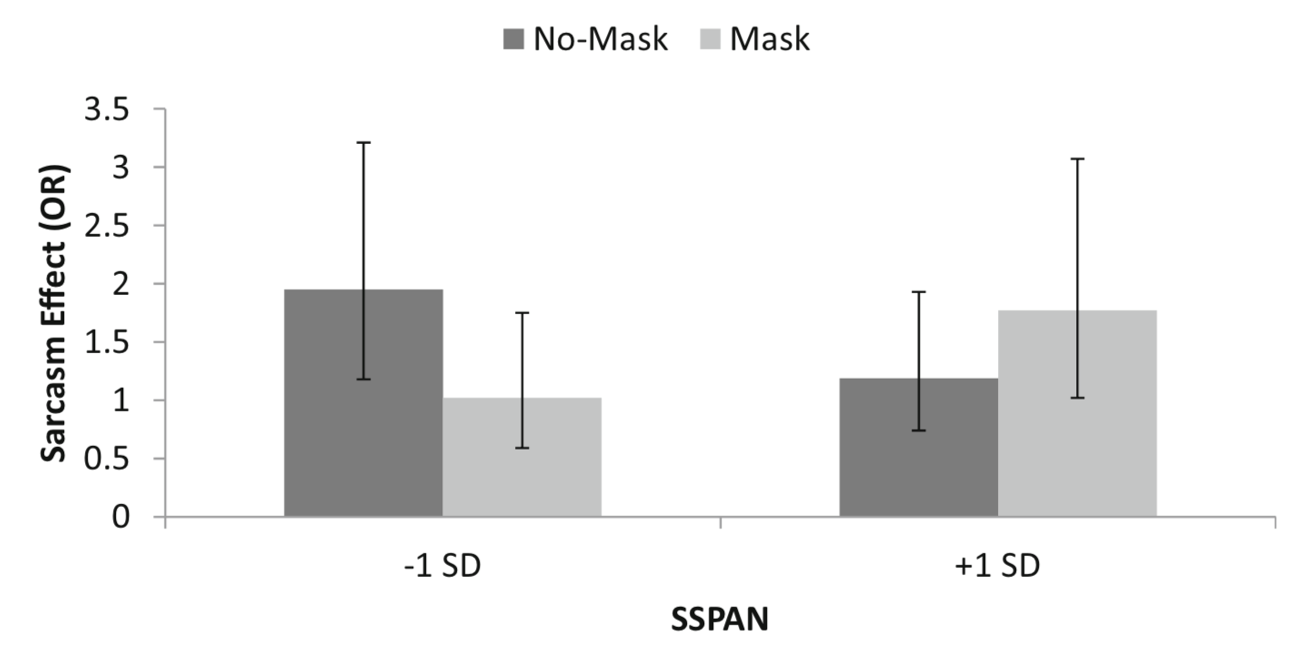

A number of interesting patterns emerged in the data. First, when the previous sentences were masked, readers were less likely to look back, regardless of whether the text was sarcastic or not. However, individuals with lower SSPANs were more likely to look back when reading sarcastic utterances than when they read literal utterances. Surprisingly, though consistent with previous results, readers with high SSPANs did the opposite, and were more likely to look back when the sarcastic sentences were masked. Below is a summary of this pattern of results. The figure shows the impact of sarcasm on look-backs by participant group (high versus low SSPAN) and reading condition (mask or no mask):

Finally, readers had better memory for material with sarcastic sentences in them than ones that contained literal sentences; additionally, participants took longer to answer questions about sarcastic sentences than literal ones. However, even though participants took longer to read sarcastic sentences, taking longer did not necessarily make participants more accurate in the comprehension questions.

On a global level, the results tell us that individual differences in working memory capacity influence whether, where, and how much a reader looks back to an earlier part of a text. It is clear that readers use a spatial representation of the text that they can rely on to go back if they run into a comprehension problem, ranging from misunderstanding a single word, to encountering a syntactically complex structure, to identifying and interpreting sarcasm.

Psychonomic Society article featured in this post:

Olkoniemi, H., Johander, E., & Kaakinen, J. K. (2019). The role of look-backs in the processing of written sarcasm. Memory & Cognition, 47, 87-105. DOI: 10.3758/s13421-018-0852-2.